by Mindy Fried | Jul 4, 2015 | aging, connections with people, depression, engaged aging, exhaustion, gender, health, insomnia, resiliency, sleep, women and health, work culture

The men in my family were easy sleepers. It wasn’t uncommon to see my father and his six brothers lie down on the floor after a big meal and just nod out. Of course, that left my aunts to clean up, after they had also cooked the meal, and I bet they could have used a nap too. At the time, I figured that taking a post-meal snooze was the “way things were” for the men in the family. But gradually, as I developed a feminist consciousness, I resented these lazy guys. As my age gradually crept up to where theirs were back then, I have begun to appreciate their supreme capacity to sleep just about anywhere, anytime. My father was also one of those people who could nod out for five minutes – taking a so-called “power nap” – only to emerge refreshed and able to fully re-enter the conversation when he awoke.

Later, when he was in his 90s, he began to experience serious insomnia, lying awake for hours and hours throughout the night, going crazy with boredom and frustration. While I sympathized with his dilemma at the time, it wasn’t until I experienced my own sustained insomnia – after a back injury – that I understood how horrible it is to not be able to sleep night after night. I discovered that sleep deprivation steals one’s energy, one’s optimism, and sometimes even one’s sanity. With increasing lack of sleep, the exhaustion compounds and the world becomes slightly, if not majorly, off-kilter.

Insomnia is a lot of things, which includes having a hard time getting to sleep, as well as waking up early and having a difficult time getting back to sleep. Not surprisingly, it isn’t a contemporary phenomenon. No, we in the so-called modern world didn’t invent it. Insomnia goes way, way back. The term “insomnia” first appeared in 1623, and means “want of sleep”. One of the biggest causes of insomnia, stress, is something that people have been struggling with for eons. It’s just the nature of stress that looks slightly different these days, compared to a few centuries ago. But if you think about it, there are a lot of similarities.

We’re stressed because we work hard or we don’t have enough work. We’re stressed because we live in a violent world that is unpredictable. We’re stressed if we experience social isolation or prejudice. We’re stressed when we don’t have enough to eat, and don’t know where the next meal is coming from. We’re stressed because our jobs are too demanding or not challenging enough. We’re stressed because we worry about paying our bills. We’re stressed because we don’t feel loved enough, or because we have tension with our partners or our friends. One might call these universal problems, and these stressers will vary based on your economic situation as well as your race, gender and sexual identity. And maybe a few centuries ago, we might have also worried about predators or major diseases that wiped out entire swaths of people. All of these stressors can lead to loss of sleep.

A lot of famous people are recorded as having suffered from insomnia. Sir Isaac Newton suffered from depression and had difficulty sleeping. Winston Churchill had two beds because if he couldn’t sleep in one, he would try the other. Thomas Edison, like my father, was a cat-napper, because he couldn’t sleep at night. Some insomniacs turned to drugs. Marcel Proust and Marilyn Monroe took barbiturates to help them sleep. English writer, Evelyn Waugh, took bromides to induce sleep. As we know, Michael Jackson died because of a lethal cocktail of medications to help him sleep, including propofal, used for sedation before surgeries, lorazepam, used for anxiety, and a host of other meds, including midazolam, diazepam, lidocaine and ephedrine. He was obviously so desperate to sleep that he was willing to try them all.

Author and columnist Arianna Huffington calls insomnia a “feminist issue”, and has written columns in Huffington Post lamenting her lack of sleep from jet lag. Another Huff Post columnist, Dora Levy Mossanen, calls insomnia a “smart, devious virus that mutates and changes form every season like the flu virus. Except that this tricky bugger is tuned to our circadian rhythm and is able to change and disguise itself at whim to confuse the heck out of us”. Mossanen does all the “right things”: She doesn’t drink caffeine, goes to bed at a decent hour, drinks hot milk before bedtime, takes warm baths, reads non-stimulating books, listens to guided meditation on her i-pod, and imagines serene seashores. And yet she says, “I toss and turn at the beginning of the night, counting backwards and forwards so many times that if my mind was prone to mathematics, I’d have solved all the mathematical problems of the world by now”.

For the most part, my insomnia has cleared, but every so often it rears its ugly head. While in the midst of a minor insomniac “relapse”, I asked my friends and colleagues for their insomnia narratives. I wanted to know how long their insomnia lasted, why they thought they were struggling with sleep; what they did when they were awake; how it affected them the next day. I learned that the main causes of insomnia are:

* Anxiety, the everyday kind like preparing to teach a class, and larger anxieties, like worrying about keeping a job;

* Depression, which impedes relaxation necessary to fall and stay asleep;

* Medications, because some meds like decongestants and pain meds keep us awake. Antihistamines might initially make us groggy, but they can cause excess urination which gets us up a lot during the night;

* Alcohol, which may make you more relaxed, but prevents deeper stages of sleep and can cause you to wake up in the middle of the night;

* Chronic pain, which is distracting and worrisome and can lead to anxiety, which prevents sleep;

* Medical conditions, like arthritis, cancer, heart disease and Parkinson’s disease, which are linked with insomnia;

* Poor sleep habits, like weird sleep schedules, or an uncomfortable sleep environment;

* “Learned insomnia” – which is worrying too much about not being able to sleep, which makes it hard to get to sleep; and

* Eating too much before sleeping or eating the wrong snack, which can give you heartburn and make it uncomfortable to fall sleep.

In response to my call for insomnia stories, only women replied. I know that isn’t because men don’t experience insomnia; but perhaps men don’t want to reveal their sleeping problems publicly, even though I promised confidentiality. (It’s not too late, for my male readers!)

One woman said, “You do realize you’ve opened the floodgates, yes? Amazing topic. Of course, I’m too sleep-deprived and deep into end-of-semester madness to respond right now! Maybe during my next bout of insomnia (perhaps tonite). ;-)”

Here are a few responses from other insomniacs:

One woman says, “Funny you should ask, as I am suffering from insomnia just now, maybe a week long bout this time, but by far not the longest ever. I wake up about 4am and cannot fall back asleep if my life depended on it. Not sure why I have such a hard time staying asleep, maybe it’s hormonal (menopause) or maybe it’s all the craziness at the office (new department chair, no office support as the old secretary retired, research lagging, …). Often I am not the only one awake, as my spouse is also a stressed-out insomniac. I typically try to fall back asleep, but if it doesn’t happen, I get up and read in the living room until I feel exhausted from being up at 4 am. What sometimes works is counting backwards from 100 in another language. Needless to say, the next day I feel a bit out of it, but nothing like the “zombieness” I did when my child used to wake me up. I am not desperate yet, but may try to find my melatonin from the previous bout to get me back on track. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t”.

Another woman says, “My insomnia stories are boring. I get up and clean the house, read, catch up and/or get ahead on my work. That makes me feel like I am not wasting my time trying to fall asleep. Usually that day I am racing, energetic and feel good about all I have accomplished. By that night I am crashing and I pay the next day in bodily aches/pain. Not very exciting…”

Another says, “I have had quite a few episodes of insomnia. There were times when I would go days or even a week without adequate sleep. I would either fall asleep and then wake up in the middle of the night and not be able to go back to bed, or I would just simply stare at the ceiling until I finally fell asleep, only to wake up about every half an hour for the rest of the night. Either way, insomnia sucks! I eventually couldn’t take it any longer and sought medical help. Come to find out, I have general anxiety disorder and that was greatly affecting my sleep. Even now – I am on medication- I still have bouts of insomnia when I am highly stressed. My mind is constantly going, so when something important is coming up I find myself having trouble sleeping. In the middle of the night I have tried a number of things: read a book, go to the gym (thank you, 24 hour fitness), eat, watch TV, and try and go back to sleep. As a student, during the day I am pretty much reading, writing, researching, or preparing for a class I TA for.

“After a night of insomnia, I usually feel terrible the next day. Even if I am tired, I don’t try and nap because if I do, the likelihood of getting a good night’s sleep decreases. If I go a few days or even a week without sleep, my brain has pretty much checked out. I go through the motions but I don’t feel like I am really all there. Hopefully that makes sense. Insights? I would say that everyone is different and should try different things to help them sleep. I hate taking medicine, even when I am sick, so seeing a doctor was the last thing on my list. I tried doing yoga, eating better, not watching TV or reading at night…but nothing helped me. Being put on medication was a great relief because I sleep really well, for the most part”.

And finally, one of my neighbors says, “Sometimes I look out the window to see who else might be up in the neighborhood. I am tempted to text them or call and get together, maybe we should start an insomniac club”.

That sounds tempting… I suppose that one strategy I’m employing is writing this post. Maybe “outing myself” as an insomniac will help diffuse the potency of this insidious problem. If I were to characterize my current “brand” of insomnia, it’s “learned insomnia”, meaning that I begin to fall asleep and then just as I’m fading into a hazy fog, my brain says “you’re falling asleep”, at which point I’m awake! Luckily, the problem has lessened since I first put out the call for insomnia stories. May it fade away!

Tell me your insomnia story! What has helped you overcome your sleeplessness?

by Mindy Fried | May 5, 2013 | aging, anxiety, community, depression, homophobia, insomnia, prejudice, racism, sexism, stress, women and health, work

The men in my family were easy sleepers. It wasn’t uncommon to see my father and his six brothers lie down on the floor after a big meal and just nod out. Of course, that left my aunts to clean up, after they had also cooked the meal, and I bet they could have used a nap too. At the time, I figured that taking a post-meal snooze was the “way things were” for the men in the family. But gradually, as I developed a feminist consciousness, I resented these lazy guys. As my age gradually crept up to where theirs were back then, I have begun to appreciate their supreme capacity to sleep just about anywhere, anytime. My father was also one of those people who could nod out for five minutes – taking a so-called “power nap” – only to emerge refreshed and able to fully re-enter the conversation when he awoke.

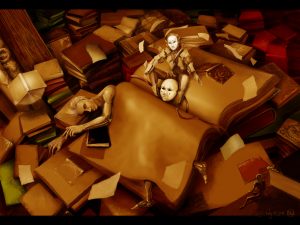

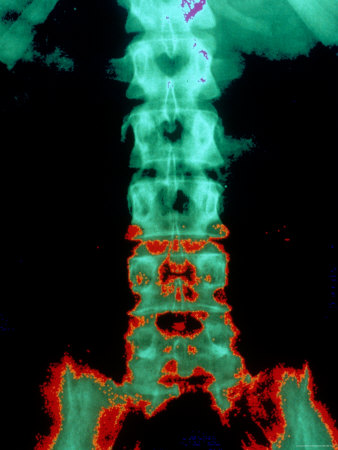

Later, when he was in his 90s, he began to experience serious insomnia, lying awake for hours and hours throughout the night, going crazy with boredom and frustration. While I sympathized with his dilemma at the time, it wasn’t until I experienced my own sustained insomnia – after a back injury – that I understood how horrible it is to not be able to sleep night after night. I discovered that sleep deprivation steals one’s energy, one’s optimism, and sometimes even one’s sanity. With increasing lack of sleep, the exhaustion compounds and the world becomes slightly, if not majorly, off-kilter.

![]()

Insomnia is a lot of things, which includes having a hard time getting to sleep, as well as waking up early and having a difficult time getting back to sleep. Not surprisingly, it isn’t a contemporary phenomenon. No, we in the so-called modern world didn’t invent it. Insomnia goes way, way back. The term “insomnia” first appeared in 1623, and means “want of sleep”. One of the biggest causes of insomnia, stress, is something that people have been struggling with for eons. It’s just the nature of stress that looks slightly different these days, compared to a few centuries ago. But if you think about it, there are a lot of similarities.

We’re stressed because we work hard or we don’t have enough work. We’re stressed because we live in a violent world that is unpredictable. We’re stressed if we experience social isolation or prejudice. We’re stressed when we don’t have enough to eat, and don’t know where the next meal is coming from. We’re stressed because our jobs are too demanding or not challenging enough. We’re stressed because we worry about paying our bills. We’re stressed because we don’t feel loved enough, or because we have tension with our partners or our friends. One might call these universal problems, and these stressers will vary based on your economic situation as well as your race, gender and sexual identity. And maybe a few centuries ago, we might have also worried about predators or major diseases that wiped out entire swaths of people. All of these stressors can lead to loss of sleep.

![]()

A lot of famous people are recorded as having suffered from insomnia. Sir Isaac Newton suffered from depression and had difficulty sleeping. Winston Churchill had two beds because if he couldn’t sleep in one, he would try the other. Thomas Edison, like my father, was a cat-napper, because he couldn’t sleep at night. Some insomniacs turned to drugs. Marcel Proust and Marilyn Monroe took barbiturates to help them sleep. English writer, Evelyn Waugh, took bromides to induce sleep. As we know, Michael Jackson died because of a lethal cocktail of medications to help him sleep, including propofal, used for sedation before surgeries, lorazepam, used for anxiety, and a host of other meds, including midazolam, diazepam, lidocaine and ephedrine. He was obviously so desperate to sleep that he was willing to try them all.

![]()

Author and columnist Arianna Huffington calls insomnia a “feminist issue”, and has written columns in Huffington Post lamenting her lack of sleep from jet lag. Another Huff Post columnist, Dora Levy Mossanen, calls insomnia a “smart, devious virus that mutates and changes form every season like the flu virus. Except that this tricky bugger is tuned to our circadian rhythm and is able to change and disguise itself at whim to confuse the heck out of us”. Mossanen does all the “right things”: She doesn’t drink caffeine, goes to bed at a decent hour, drinks hot milk before bedtime, takes warm baths, reads non-stimulating books, listens to guided meditation on her i-pod, and imagines serene seashores. And yet she says, “I toss and turn at the beginning of the night, counting backwards and forwards so many times that if my mind was prone to mathematics, I’d have solved all the mathematical problems of the world by now”.

For the most part, my insomnia has cleared, but every so often it rears its ugly head. While in the midst of a minor insomniac “relapse”, I asked my friends and colleagues for their insomnia narratives. I wanted to know how long their insomnia lasted, why they thought they were struggling with sleep; what they did when they were awake; how it affected them the next day. I learned that the main causes of insomnia are:

* Anxiety, the everyday kind like preparing to teach a class, and larger anxieties, like worrying about keeping a job;

* Depression, which impedes relaxation necessary to fall and stay asleep;

* Medications, because some meds like decongestants and pain meds keep us awake. Antihistamines might initially make us groggy, but they can cause excess urination which gets us up a lot during the night;

* Alcohol, which may make you more relaxed, but prevents deeper stages of sleep and can cause you to wake up in the middle of the night;

* Chronic pain, which is distracting and worrisome and can lead to anxiety, which prevents sleep;

* Medical conditions, like arthritis, cancer, heart disease and Parkinson’s disease, which are linked with insomnia;

* Poor sleep habits, like weird sleep schedules, or an uncomfortable sleep environment;

* “Learned insomnia” – which is worrying too much about not being able to sleep, which makes it hard to get to sleep; and

* Eating too much before sleeping or eating the wrong snack, which can give you heartburn and make it uncomfortable to fall sleep.

In response to my call for insomnia stories, only women replied. I know that isn’t because men don’t experience insomnia; but perhaps men don’t want to reveal their sleeping problems publicly, even though I promised confidentiality. (It’s not too late, for my male readers!)

One woman said, “You do realize you’ve opened the floodgates, yes? Amazing topic. Of course, I’m too sleep-deprived and deep into end-of-semester madness to respond right now! Maybe during my next bout of insomnia (perhaps tonite). ;-)”

Here are a few responses from other insomniacs:

One woman says, “Funny you should ask, as I am suffering from insomnia just now, maybe a week long bout this time, but by far not the longest ever. I wake up about 4am and cannot fall back asleep if my life depended on it. Not sure why I have such a hard time staying asleep, maybe it’s hormonal (menopause) or maybe it’s all the craziness at the office (new department chair, no office support as the old secretary retired, research lagging, …). Often I am not the only one awake, as my spouse is also a stressed-out insomniac. I typically try to fall back asleep, but if it doesn’t happen, I get up and read in the living room until I feel exhausted from being up at 4 am. What sometimes works is counting backwards from 100 in another language. Needless to say, the next day I feel a bit out of it, but nothing like the “zombieness” I did when my child used to wake me up. I am not desperate yet, but may try to find my melatonin from the previous bout to get me back on track. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t”.

Another woman says, “My insomnia stories are boring. I get up and clean the house, read, catch up and/or get ahead on my work. That makes me feel like I am not wasting my time trying to fall asleep. Usually that day I am racing, energetic and feel good about all I have accomplished. By that night I am crashing and I pay the next day in bodily aches/pain. Not very exciting…”

Another says, “I have had quite a few episodes of insomnia. There were times when I would go days or even a week without adequate sleep. I would either fall asleep and then wake up in the middle of the night and not be able to go back to bed, or I would just simply stare at the ceiling until I finally fell asleep, only to wake up about every half an hour for the rest of the night. Either way, insomnia sucks! I eventually couldn’t take it any longer and sought medical help. Come to find out, I have general anxiety disorder and that was greatly affecting my sleep. Even now – I am on medication- I still have bouts of insomnia when I am highly stressed. My mind is constantly going, so when something important is coming up I find myself having trouble sleeping. In the middle of the night I have tried a number of things: read a book, go to the gym (thank you, 24 hour fitness), eat, watch TV, and try and go back to sleep. As a student, during the day I am pretty much reading, writing, researching, or preparing for a class I TA for.

“After a night of insomnia, I usually feel terrible the next day. Even if I am tired, I don’t try and nap because if I do, the likelihood of getting a good night’s sleep decreases. If I go a few days or even a week without sleep, my brain has pretty much checked out. I go through the motions but I don’t feel like I am really all there. Hopefully that makes sense. Insights? I would say that everyone is different and should try different things to help them sleep. I hate taking medicine, even when I am sick, so seeing a doctor was the last thing on my list. I tried doing yoga, eating better, not watching TV or reading at night…but nothing helped me. Being put on medication was a great relief because I sleep really well, for the most part”.

And finally, one of my neighbors says, “Sometimes I look out the window to see who else might be up in the neighborhood. I am tempted to text them or call and get together, maybe we should start an insomniac club”.

That sounds tempting… I suppose that one strategy I’m employing is writing this post. Maybe “outing myself” as an insomniac will help diffuse the potency of this insidious problem. If I were to characterize my current “brand” of insomnia, it’s “learned insomnia”, meaning that I begin to fall asleep and then just as I’m fading into a hazy fog, my brain says “you’re falling asleep”, at which point I’m awake! Luckily, the problem has lessened since I first put out the call for insomnia stories. May it fade away!

Tell me your insomnia story! What has helped you overcome your sleeplessness?

by Mindy Fried | May 8, 2012 | arts, depression, education, finding work, graduating from college, making choices, unemployment, women and work

As our daughter goes into her final year of college, I have begun to feel a sense of trepidation about what comes next. The seniors I taught this past semester are already going into panic mode as they face a very uncertain future. Regardless of all the internships and community service experiences they are accruing, there’s no avoiding the dour statistics for young college graduates. When one student came to me, asking for advice about applying for a consulting job that was way beyond her reach, I found myself counseling her about the virtues of working in a coffee shop. So what if she’s an international relations major!

My first “real” job after graduating college was working in a state psychiatric hospital. This seemed like a “natural” place to be, since one whole side of my family was riddled with serious psychiatric disorders. Between an aunt with agoraphobia who never left her house, an aunt and an uncle who had “manic-depression” (now called bipolar disorder, a much more “respectable” name), and a mother who struggled with clinical depression and alcoholism, I was quite at home working in an institution for people with severe mental health problems.

I had been a dancer for many of my young years, and my professional goal – if one could call it that– was to somehow combine my interest in helping people with my passion for dance. I lucked out, since the field of dance therapy was just emerging, and one of the first certified dance therapists in the U.S. was willing to train me during my senior year of college. When I graduated, the state psych hospital was hiring tons of young college graduates. This was the early ‘70s, when thousands of patients, people who had spent years, sometimes decades, living in inside the walls of state hospitals, were released into the community in a move to “de-institutionalize” them. The motive was humanitarian, but the upshot for many of the patients was downright cruel. Nonetheless, it did mean that a lot of my friends and I had jobs.

I was hired as the institution’s dance therapist – and worked with people who were still living “inside” the institution, as well as out-patients that were being transitioned into a day treatment program. I fell in love with schizophrenics who were smart and spoke in metaphors that seemed poetic and deep. Because I was a professional dancer in a mental hospital, many of the institution’s rules did not seem to apply to me. Or at least that’s what I thought and how I behaved… More than once, I led a group of patients in a snake line through the hallways, and we seemed off-limits to criticism, as this “crazy” activity was “therapy”! It felt downright revolutionary!

While this experience – working in an institution – wasn’t where I “landed” professionally, it was nothing short of a profound experience. I will never forget one of my out-patients, a diminutive woman named Ruth, who had spent her entire adult life imprisoned in the psych hospital. Ruth held her body like a tight fist, and stood all day, rocking rhythmically back and forth. I still feel teary when I think about her. There was another man who is seared in my mind: a tall, broad gentleman in a perpetual cowboy hat who people called “the Captain”. He was a man of few words, and those words were garbled, but he had a jovial demeanor. One of my most glorious days with him was when I took him for drive in the country, with two other patients. Outside it was minus forty degrees; but inside the car, with sun shining through the windows, it felt warm and protective. He said little throughout this drive, just smiled…

By the time I had been hired to work as a dance therapist at the state psych center, sociologist Erving Goffman had already published his seminal book Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. One of Goffman’s greatest contributions was his critique of what he called “total institutions”, which included mental hospitals and prisons. Goffman argued that total institutions had a high degree of regimentation, and an elaborate privilege system. He described relations between staff and patients (or inmates) as caste-like, with detailed “rules” of deference and demeanor. One of the my favorite co-workers at Hutchings, a friendly and clever guy named Willie who was the janitor, surely understood Goffman’s analysis when he changed his first name from Willie to “Doctor”. Whenever anyone wanted his services, they would yell “Doctor” and he came running with a smirk on his face.

I knew nothing of Goffman while I was working in an institutional setting. But now, as I reflect on my first post-college job, and after studying this brilliant sociologist in graduate school and using his analyses in a class I now teach about the sociology of aging, it all comes back to me. First, I lived what Goffman described and then I was able to understand his theoretical frameworks, drawing upon my own experience. As my father used to say, everything we do in life accrues and has meaning. This has to be true, as well, for college students who are graduating to a lousy economy and a dearth of employment opportunities that “fit” with their majors.

Despite the draw of my first job, I realized within a year that I wasn’t going to last. I was too young, too inexperienced and too critical of the institution to stay. While I found the out-patients I was assigned to counsel interesting, I had no real training. And even though I was a good listener, I fought back tears every time a “client” expressed sadness or joy. What drove me to work at this state psych hospital – working with really troubled people – ultimately became the reason I had to leave. Ultimately, it wasn’t the right fit, even though it seemed right at the time. With a far more robust economy than we have today, I had saved up enough cash that year to travel in Europe for nearly a year, and that’s what I did!

While my career as a dance therapist came to a halt, my original passion – dance – continued to be my life-line for decades until around ten years ago, when I experienced a serious injury. For a year, I was in persistent pain and could barely move, much less dance. With the sudden loss of the activity that centered me and gave me such joy, I plunged into a deep depression and felt overtaken by panic, fearful that I would never heal. Like many back-pain sufferers, I bounced around to various practitioners, many of whom got frustrated with me because I wasn’t getting better. In one pain clinic, a doctor yelled at me, saying that I was fine. In another back healing program, a doctor challenged ME to figure out what the problem was, because she could not. Other practitioners told me that I wouldn’t heal if I stayed depressed and anxious. A true chicken and egg problem…

During this time, I had a glimpse of what my patients from many years before had experienced. The one person who comes to mind, in particular, is a young woman who was around my age and had participated in an ongoing dance session I held for outpatients. I never knew what her story was; only that she was struggling with depression and had obviously spent time in the hospital itself, which meant that she had been in the role of “patient”, complete with the dehumanization that comes with that experience. She came up to me after one of our dance sessions and thanked me, saying it was the one thing in that setting made her feel “normal”.

How are young, college-educated people dealing with this lousy economy, saddled with debt and poor prospects for a job? A number of young people I know are living at home, and working in unpaid internships that they hope will lead to a paid job. I know one young person who dropped out of college in her freshman year and learned how to do organic farming. Now she’s running a business where she creates peace gardens for interested clients. And I know another young person who couch-surfed for a few months, and then got a job sailing someone’s boat down to the Virgin Islands. At one point, during an intense storm, he wondered if he was even going to make it… I can imagine that he is not the only one feeling that way.

Over time, I have come to realize that we humans are drawn to different types of work at different stages of our lives, and often there is a reason. I happened to work at a mental hospital because it grabbed me emotionally – and that’s where there were jobs. But even then, when the economy was decent, that first job out was hit or miss. The thing that sustained me was dance. It continues to be my way in, and my way out. When I think about my own daughter – and all the young people I encounter these days – what I wish for them is the courage to follow their passion, and then feel okay about whatever job or internship (or whatever) they find, knowing that those things may not be the same thing. At least for now.

by Mindy Fried | Sep 30, 2010 | child care, depression, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, women artists

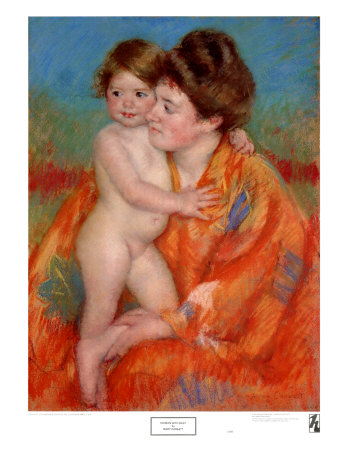

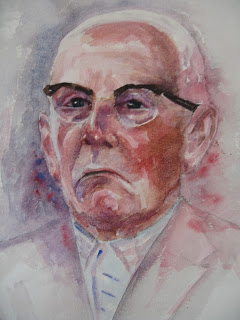

This is a picture of me and my mother. You’d never know from looking at the expression on her face that she hated being a “homemaker”. In fact, she looked pretty happy hanging out with me, even if we were washing dishes! In her younger years, prior to the birth of her two daughters, she wrote sultry torch songs and had her own radio show. Later, she studied painting and then continued to paint portraits until her final days. When I was a teenager, she exhibited her paintings every year in an outdoor art festival, near a studio she rented in what was considered the bohemian part of Buffalo, New York, my home town. Despite being an adolescent, this was the one and only weekend – every year – that I thought my mother was really cool.

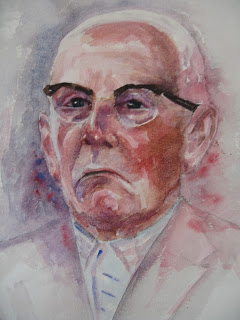

Here is one of her watercolors that I still really love. Middle-class women of my mother’s generation – caught between the suffragettes of the early twentieth century and the second wave of the women’s movement of the 1970s – did not have an organized “sisterhood” of women supporting them to step out of the kitchen. As an artist, my mother was passionate about her work, but it was never considered a career, nor did it generate much income, even though she taught painting and sold commissioned portraits. In fact, in her era of young motherhood – the 40s and 50s – single middle-class women who worked for pay were expected to leave their jobs once they were married. As we know now, the independence of women is often tied to their earning capacity, and not being considered a professional was hard on her. This phenomenon was eventually coined the “problem without a name” by Betty Friedan.

My mother’s favorite artist, Mary Cassatt, is quoted as saying:

“There’s only one thing in life for a woman; it’s to be a mother…A woman artist must be…capable of making primary sacrifices.”

How ironic, given that Cassatt never married, nor did she have children; and for many years she painted portraits of mothers and children!

Reflecting the schizophrenic existence of a strong-willed woman of that era, Cassatt also said,

“I am independent! I can live alone and I love to work!”

Even though her family objected to her becoming a professional artist, Cassatt began studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia – where my mother also studied art for one year. I never spoke to my mother about why she left, but Cassatt also left after one year, complaining that “there was no teaching” at the Academy. Unlike male students, females couldn’t use live models. This is likely just one of the inequities she encountered there. When she left, Cassatt moved to Paris. When my mother left, she moved back to Buffalo, New York…

My mother’s life was one of sacrifices, like so many women of her generation. The arts were a place for talented and creative women for whom other professional careers were closed. Maybe it was a vestige of the Victorian era when it was considered proper for upper-class girls and women to “dabble” in the arts. To be considered a serious artist was another thing though. And my mother always struggled to be considered a professional. It irked her when the realists or even the abstract expressionists – always male – won the competitions she entered. She intuitively understood that there was gender bias, but the proof was invisible. To be an artist means expressing oneself – putting one’s vision into the universe to challenge and inspire or simply to portray beauty. In an era where women’s voices were not heard, being a woman artist was revolutionary.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

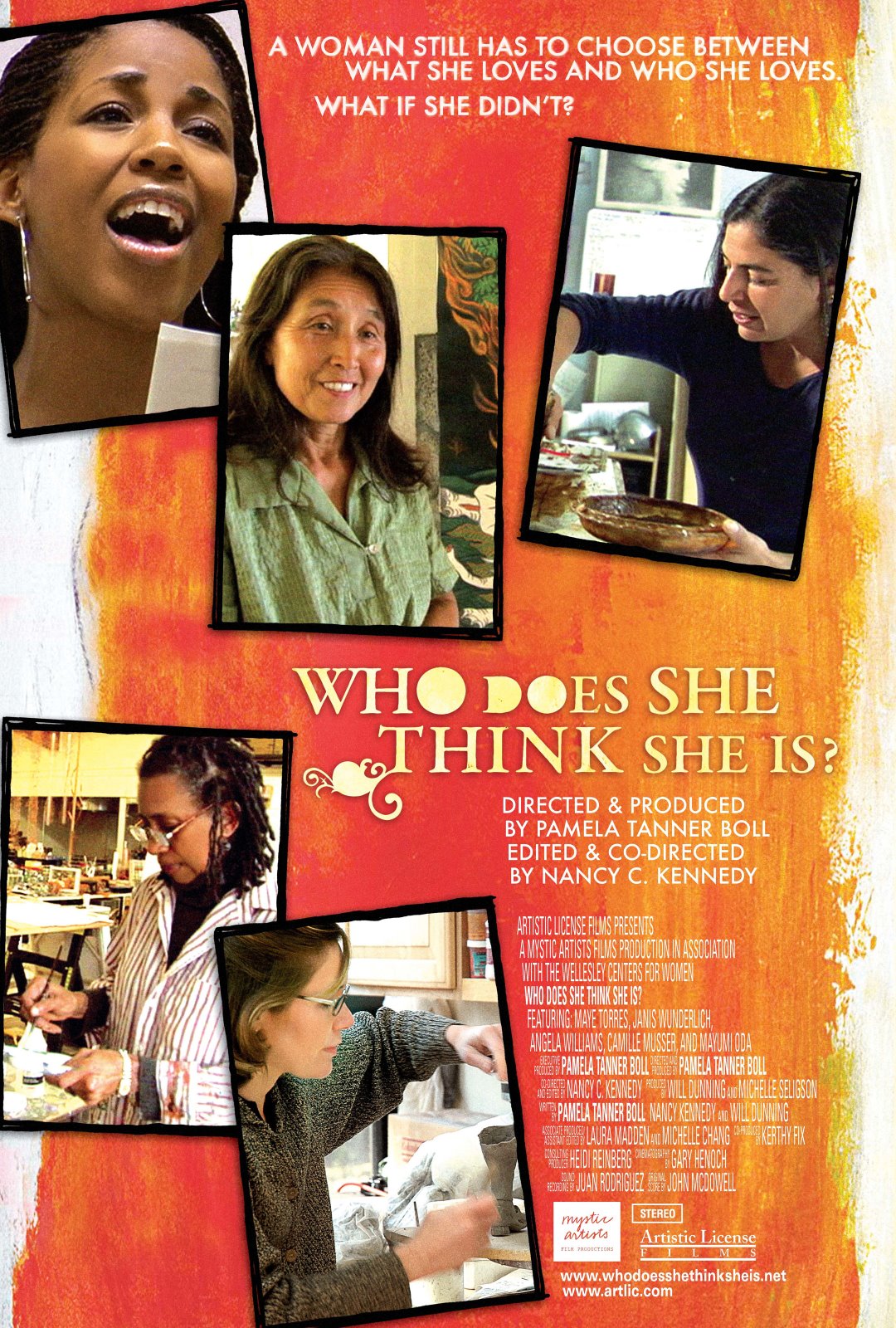

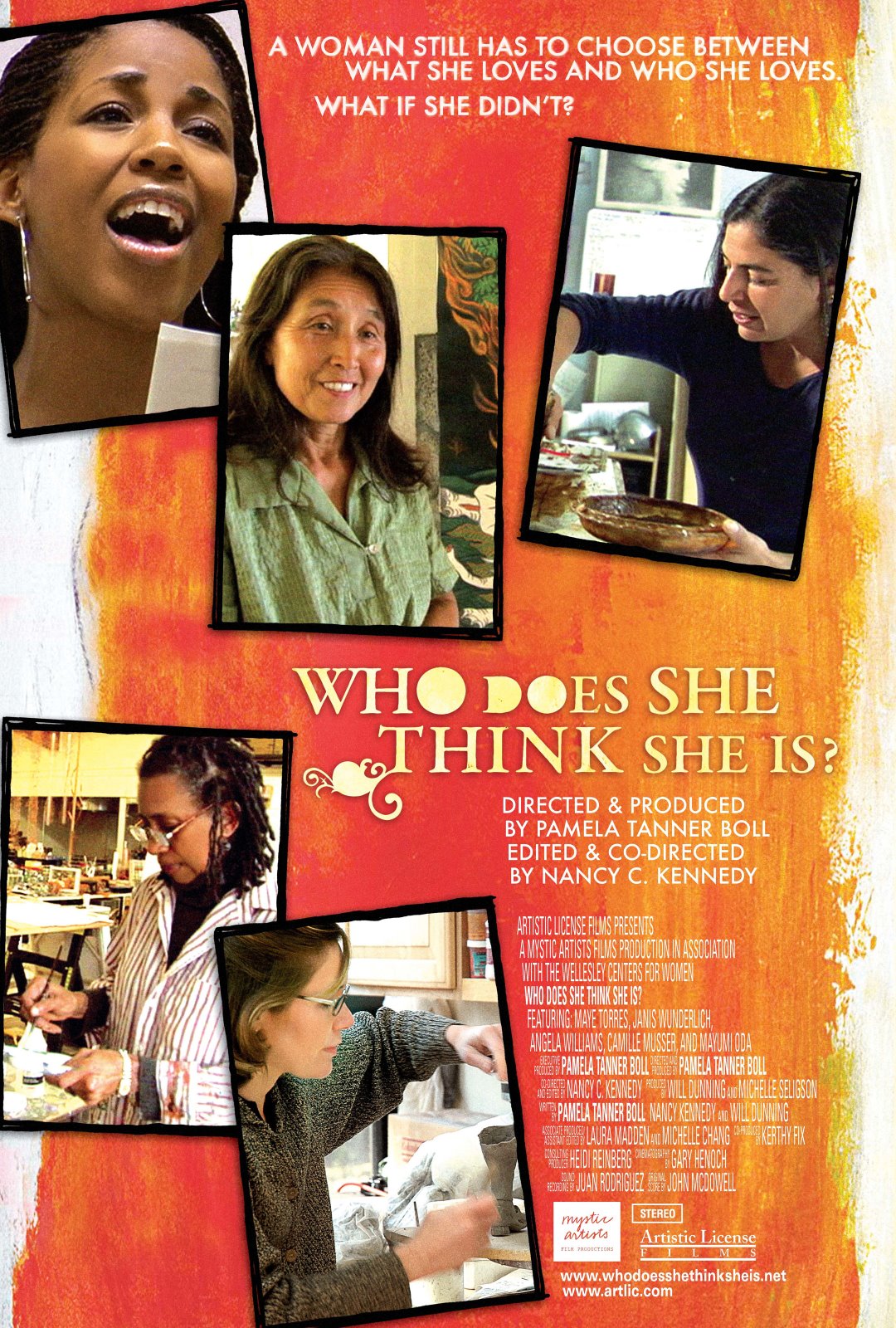

In a film about women artists called “Who does she think she is? – produced by Pamela Tanner Boll (who also produced Born into Brothels) – artists reflect on the challenges they face balancing their work and family demands.

They talk about how they’re not taken seriously precisely because they’re women. In fact, while 80% of students in visual arts schools are women, “in the real world,” 70-80% of artists whose works are shown in galleries and museums are male.

In an article in the New York Times, Marci Alboher says these statistics “sound alarmingly like the numbers released by organizations that track the presence of women in the highest echelons of professions like law, journalism, engineering or finance.” The women artists in the film also argue that they are dissuaded from focusing their art on the subject of mothers and children, because it is not considered “real” material. Both artist and subject are devalued…

Outside the art world, says Alboher, people rarely discuss the challenges faced by women artists “moving up the ranks.” This has a lot to do with the fact that women are still considered primary caregivers in this society. Despite the large percentage of mothers in the labor force, we are still defined primarily by our capacity to bear children. Most workplaces do not accommodate the need for work-life balance for their employees, be they women or men.

As a teenager, I was often frustrated by my mother’s lack of confidence in her work. I wanted her to be a strong role model in many ways, someone who followed her passion and knew she had talent as an artist. But now I have an increased understanding of the effects of working in isolation, in a society that didn’t value the work of women artists, and in the microcosm of that society, in a family that expected her to have dinner on the table every night. (No wonder she hated to cook!)

I love the comment by Georgia O’Keefe who once said,

“I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking the time to look at it. I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

It takes guts to think that your painting will stop New Yorkers in their tracks! But while guts are good, women’s voices need to be valued; the balance of caregiving must be shared; workplaces need to accommodate the work-life balance needs of parents; and social policy must broaden to include paid parental leave and universal, free early care and education.

According to a 2008 National Endowment for the Arts report called “Artists in the Workforce: 1990-2005”, women artists are as likely to marry as women workers in general, but… they are less likely to have children! Only 29% of women artists had children under 18, almost six percentage points lower than for women workers in general. So like Cassatt, it appears that many contemporary women artists have decided to avoid the social institution of motherhood.

The incredible Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo, once said, “Painting completed my life.” I think my mother felt the same way, even though she never achieved traditional “success” as a painter…

by Mindy Fried | Jul 3, 2010 | depression, finding work, unemployment, women and work, work statistics

Every so often, someone – generally some man – will ask me if I work, or even better, if I still work. In the past, this comment meant: Are you a “stay-at-home mom” (first reference), ergo, not doing “more important” work in the paid labor force; or are you retired because you’re old or don’t “need” to work (second reference)? Jeez! Most women – including those with kids – work for pay. And I’d like to think that I’m still “in my prime” in terms of my labor market participation. The truth is that, like so many Americans, I work like a maniac. Why? Because I have to; I derive pleasure and purpose from it; and hopefully I can contribute something meaningful to the world… But there’s a new interpretation to that question about whether I – or any of us – work, and it has to do with the increasing normalcy of unemployment.

Despite all the government’s attempts at jump-starting the economy, the rate of unemployment has remained stubbornly high at around 10%. A recent rise in the job rate was more related to the creation of temporary jobs. In fact, some of my friends who got hired as census workers were part of that faux decrease in the unemployment rate, and when their jobs end, the unemployment rate will likely go up. Unemployment affects people from all walks of life, but it disproportionately affects people of color. For example, the unemployment rate for white men is 8%, compared to a whopping 17.1% for African-American men and 11.1% for Latino men. The unemployment rate for white women is 7.4% versus 12.4% for African-American women and 10.3% for Latinas.

In this current recession, men initially experienced higher job losses than women, because the industries first hit – like housing, construction and manufacturing – are dominated by men. But downsizing has become an increasingly gender-neutral phenomenon. As the recession has expanded, women are losing more jobs and at a slightly faster rate than men in key sectors like retail and service work. According to Valerie Norton, a Public Policy Fellow at the National Women’s Law Center, in January, 2009, women’s unemployment was at the highest rate in 16 years and had the largest single-year increase in 33 years.

In the past few weeks, I have had numerous conversations with friends and acquaintances about the difficulty they’re having finding a job, or how they’re worried about being laid off from their current job. There’s the 20-something armed with degrees who has been thinking about launching a business and meanwhile is working in unpaid internships. There’s the highly educated manager who thought her job was stable, but her organization doesn’t have the funds to cover her, so she’s scrambling to network with contacts near and far. And there’s that person I knew ten years ago and haven’t heard from in ages who suddenly asked me to “link in”. I don’t blame her; I’d be doing the same thing.

I empathize with each of their circumstances. I’ve been out-of-a-job or underemployed a few times in my life, and because I make my living as a consultant, it could happen again. The first time I was without a job, I was in my early 20s. I had worked for a year in a psychiatric hospital and saved enough money to travel in Europe for nearly a year. I came back home – job-less – to an icy, grey Syracuse, New York winter, with no prospects or plans. Poor me… (you think). I had the time of my life, being carefree, so it’s probably hard to “feel my pain.” But I discovered a very dark place emotionally that lingered for months. Although I only had me to support, I was still terrified of the abyss that seemed to lie in my future. Ultimately, I ended up in graduate school, that legitimating haven for the unemployed (that is, those who can afford it time-wise and financially). With a nice scholarship, I had returned to the familiar womb of education, which paid off when I re-entered the job market. My second experience of unemployment was equally tough and unfortunately, I didn’t seem to have learned anything from my first experience. I was quite adept at internalizing the depression of the economy, fighting an internal battle about my value to society, until I again landed back on my feet with a new job.

Like many a sociologist, I have sought to understand life’s experiences by broadening the palette of my own mind and studying the phenomenon. Over the years, I have done a number of workplace studies, and invariably, even if the study isn’t about UN-employment, it becomes about unemployment or, equally difficult, about the challenges of working in dysfunctional workplaces. From my vantage point, most workplaces have a touch of crazy, and well-adjusted employees recognize this and maintain some perspective.

In one workplace study I did in six major corporations, examining the impact of flexible work policies on bottom line issues, two of the participating companies announced lay-offs during the course of the study. In one case, managers from around the country were brought into an auditorium, where the CEO announced the downsizing plan, charging the managers with the task of executing it. As you can imagine, the waves of fear and anger rippled throughout the corporation. In another company, the two top guys in the firm released a video which all employees watched at the same time, in which they sat comfortably in their mahogany wood-paneled office and speaking directly into the camera, announcing major lay-offs, and audaciously suggesting employees now had the opportunity to spend more time with their families. Seriously?! All the people I interviewed at that company were scrambling to figure out their next move, all second-guessing who was on “the list”. They were furious and they felt betrayed.

In another corporation, I was hired to conduct research on why people were leaving their jobs, and then the corporation announced it was downsizing thousands of employees. What were they thinking?! My work partner and I spent three years conducting phone interviews with 350 people about “why they were leaving” and invariably, the interview became a phone therapy session about how they felt betrayed by the company. In one unit, contract workers were brought in before the long-term employees left. Most (yes most) of the workers we interviewed in this unit confided in us that they were seeing a psychiatrist and taking Prozac. We just wanted to say to them, ‘Talk to your co-workers! You’re not alone!’ But confidentiality didn’t allow that…

One of the hardest hit groups is unmarried women, many of whom are mothers or caregivers. According to Liz Weiss and Heather Boushey, economists from the Center for American Progress, “The high unemployment of unmarried women, and particularly the 1.3 million unemployed female heads of household who are primary breadwinners for their families, is devastating to their financial circumstances and standard of living.” Unmarried women have much higher unemployment than married women. In October, 2009, 10.3% of unmarried women age 20 and over and 5.7% of married women were unemployed.

Losing a job usually means losing employer-supported health insurance, which is one reason why national health care reform is so critical. Weiss and Boushey report that there are an additional 276,000 children of unemployed single mothers who no longer have access to health insurance. Poverty rates for unmarried women are usually much higher than for married women (20.8 percent versus 6.2 percent of women 18 and over in 2008, the most recent data available), and poverty rates are probably higher because of growing unemployment.

At the policy level, we need an infusion of funds into job creation and job training programs, and better family policies to support women and men when they are “inbetween” jobs. Universal early childhood education, paid family leave and universal non-stigmatized family allowances would go a long way. At the personal level, it looks like those with more education experience less job loss, so this is another area that requires government policy and support.

Meanwhile, the next time some one – probably some man – asks me if I’m working or still working, I will ask for clarification. Are you asking if I’m unemployed? Do I look like I have a sugar daddy or momma? Do you really think I look old enough to have retired? Or maybe I’ll just smile and say “yes”.