by Mindy Fried | Jun 24, 2012 | adventure, connections with people, giving advice, hitchhiking, making choices, memories, parenting, resiliency, sociological imagination

When I was in my early 20s, I spent a summer hitchhiking across America. I was with a good friend, Ingrid, who was ready for an adventure, and off we went with our forty-pound backpacks, starting in New York State and landing a few months later in California. Each driver who picked us up presented another set of wonders, as we listened with fascination to stories about their lives, and shared stories from our journey. One driver who picked us up in Kansas told us all about her research on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, which required that she travel across three states to visit research sites. A young person anxious to find a career, I was blown away with how cool that sounded, but we were nearly blown away when her tire exploded. Luckily – and luck was what you needed when you were hitchhiking – we were just pulling into a gas station. Unluckily, it was July 4th and the mechanics couldn’t fix the tire until the next day. We slept in the car that night inside a stuffy garage, which was offered to us as a safe haven.

When we were moving up the coast of California, a driver picked us up in a mobile home he was hired to transport. When we hopped in, we discovered two other hitchhikers, and soon found that both of them had just been released from a local prison. They had committed minor economic crimes, or so they said. Another ex-convict joined us along the way, and we all slept that night in the van. But something obviously went awry during the night, because we woke up the next morning to our driver speeding down the road and screaming at high volume to one of the women, “I’ve got a bone to pick with you!”.

Ingrid and I never found out what that bone was, but we mousily asked to be let off at the next rest stop because we said that was our destination. As he drove away, we hid behind a bush, waiting for him to leave, and then went back out on the road with our thumbs ready to find our next ride. He knew we were lying and drove around in a circle, finding us back out on the highway. We did not get back into his mobile home, and survived to tell the tale.

Hitchhiking in America was pretty standard fare for a sub-culture of counter-cultural Americans in the 70s. And two young women going on the road “alone” wasn’t considered outrageous, because we were caught in the tide of a rising second wave of the women’s movement where females could do (almost) anything. While we knew we were dancing with danger, we had youth on our side, and the sense that we could handle whatever we encountered. Later I took my travelling skills to a nearly year-long trip in Europe, and continued to welcome adventure along the way. Sometimes I think my sociological imagination was birthed on these trips.

Now I am a mother whose young adult daughter is travelling – not with her thumb – but with a bike and a girlfriend – through Europe. Unlike my travels which happened sans parental approval or even knowledge, I am in the know about this trip, thanks to a very different kind of parental-child relationship in this 21st century, and a smart phone that supports that. I am caught between experiencing vicarious thrills and experiencing terror, because I know that sometimes things can go very right and sometimes they can go very wrong.

They have been biking for over a month, and still, every morning when I wake up and look at the clock, I add six hours, and imagine what my daughter and her friend are up to. Are they on a beautiful, winding country road, biking next to sheep grazing on the side of the road? Or are they on a jagged, narrow road where cars are, at best, only nearly missing them? Have they encountered the kindness of strangers? Or have they experienced “near misses”?

Both of my trips were much less structured than my daughter’s. If I ever feared for my life during my hitchhiking trip across the U.S, it vanished the second we moved on to the next ride. Even when one of our drivers had a bayonette on his dashboard, I felt invincible and maintained my faith in the goodness of people. With my trip to Europe, which I had spent one whole year saving up for, I was part of a sub-culture of young travelers like myself, populating hostels, walking the streets with our oversized backpacks, and finding bargain meals to stretch out funds for as long as possible. My daughter and her friend are more like speedy turtles, carrying minimal clothing, a tent and other supplies on their bodies and bikes, as they follow roads through small villages and towns, and bike along the side of lakes and rivers.

When they get a flat on the side of the road, they are only more fully a part of the scenery, and even a conversation piece for the locals. They are couch-surfing, taking advantage of a miraculous network of people who offer their homes to strangers, supported by an on-line forum where people post their availability and travelers contact them. Former couch-surfers can review their experience so that prospective ones can evaluate their options. Couch surfers even evaluate the travelers too. My daughter told me that after they left their first couch surf home, their host posted that she and her friend were “like sisters and made me smile the whole time of their visit”. For the most part, life for them has been pretty darn good, even great.

Unlike with my trip, where I didn’t talk to my parents at all, my daughter and I talk every few days, thanks to Skype, and when there’s a problem, we talk more than once a day. Forty years ago, I didn’t want to talk to my parents, and maybe because it wasn’t an option, I didn’t miss it one iota. Now I can’t imagine being on my parents’ end of things, not knowing where I was or what I was doing for many months at a time. I am relieved that I can check in with my daughter, and that she has a blog page that narrates her travels with glorious pictures! I doubt that I did more than send my parents a few postcards. At the same time, just because I can stay in touch, the challenge is to not hover, because the reality is that if there is a problem, there is very little I can do from thousands of miles away, other than listen and maybe help them solve it themselves.

As our children grow up, I “get” that we need to let go, to allow them to spread their wings and learn from experiences, both good and bad. But it’s a scary world, and sometimes I’m just frightened. I’m not naïve about the potential dangers out there, but at the same time, for two young women to explore the world – especially from the vantage point of a bicycle – it is just incredible. Some friends have told me how cool I am to “let her go” on the trip; others tell me they would never have approved a trip like this. But I did. (Did I really have a choice?) And in good part, I did because my parents didn’t stop me from exploring, even though they had no idea what they should have protected me from.

I imagine that for the next few weeks – the amount of time remaining in this trip – I will calculate the time zone differences and imagine where they are in their journey. I will control the amount of contact I initiate, but will steadily follow their blog and Facebook posts. I know that the life lessons gleaned from this challenge will be more potent without mommy. And I will continue to be caught in this odd place between vicarious pleasure and terror.

by Mindy Fried | Mar 3, 2011 | family, loss, memories, organizing, social justice

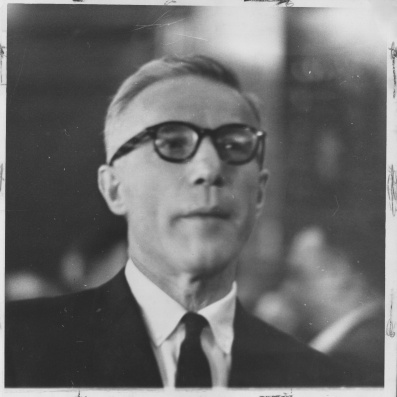

My father just died. My 98-year-old, fearless, outspoken father – who was devoted to fighting for the rights of workers – just died. He hung on for over a year, despite major organ failure, with incredible determination and will. Just the way he lived. Even towards the end, despite the challenges and limitations to his body and mind, he was energized by the protests in Wisconsin, as state workers – police, firefighters, nurses and more – fight to maintain their right to bargain collectively.

In the 40s and 50s, my father was unafraid to speak up for working-class people who toiled in factories. This was his organizing base, and as a child of the 50s, it seemed very foreign to me in my middle-class world. I was schooled by the antiwar movement, the women’s movement and gay/lesbian rights movement, all a far cry from the world of factory workers who made auto or typewriter parts.

In the 40s and 50s, my father was unafraid to speak up for working-class people who toiled in factories. This was his organizing base, and as a child of the 50s, it seemed very foreign to me in my middle-class world. I was schooled by the antiwar movement, the women’s movement and gay/lesbian rights movement, all a far cry from the world of factory workers who made auto or typewriter parts.

|

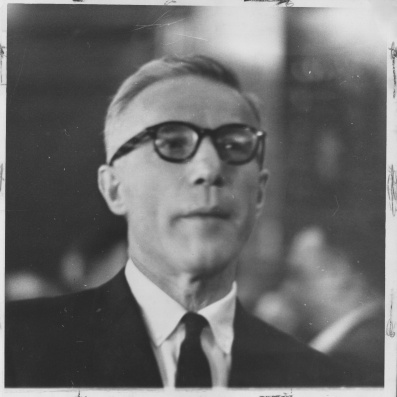

| Manny speaking before House Un-American Activities Committee 1964 |

|

But I absorbed my father’s social justice values, even though I felt very separate from the people he was organizing. It was hard for me to imagine the unfortunate plight of the factory worker, but over the years, I began to understand the need to fight against inequities around workers’ wages and working conditions. And once I was in the work world, I learned first-hand what it meant to be caught in a stratified social structure that appropriated varying amounts of power to its employees. In fact, a string of lousy work experiences was one thing that inspired me to study workplaces once I became a sociologist. I discovered first-hand that worker control is the key to job satisfaction, and many people don’t have enough of it…

I was once on a plane with a factory owner, and over the course of our flight, discovered that this guy’s plant – Remington Rand – was one that my father had organized. Listening to him talk about how he decided to move the company abroad, and how he couldn’t understand why his workers weren’t willing to move with him, I realized how out of touch he was with the reality of his workers. I knew more about him than he could have possibly known. My father had led the workers employed by that man in a successful strike against the company, and the workers forced the company to back down on cutting wages and benefits. I decided not to share this information, but found great satisfaction in knowing…

At my father’s funeral this past Sunday, I told the congregation that if he were still alive and well, he’d be in Wisconsin. This was his fight, something to which he dedicated his life, through his organizing work, and then later through plays he wrote about worker-management struggles. The nature of the “working class” is different today, as factory work has moved to locations with cheaper labor. Wisconsin workers represent the “new” working-class, whose self-identification is folded into our broadly defined middle-class. They are service and professional workers who provide the critical supports to our society – regulating safety, putting out fires, teaching our children, maintaining our sewage systems, and caring for the sick.

There are far too few heroes these days, people who are willing to stand up against adversity to speak their piece and demand justice. My father chose to do just this. It wasn’t always easy to have a father who prioritized the outside world over his family. In fact, I learned early on that if I wanted to be close to him, I had to speak his language. I tried very hard – sometimes too hard – back then. And the older and more knowledgeable I became, the more I realized where we differed. But at the very base, I valued his commitment to a set of ideals, even when they created adversity for him and for us. He always hoped that we would see he made the right choices. And in the end, as a daughter to a loving father who became more emotionally generous with age, I feel that he did.

|

| Manny receives Joe Hill Award from AFL-CIO Labor Heritage Foundation |

by Mindy Fried | Aug 16, 2010 | family, immigrants, Jewish history, memories, women and work

There is a rising anti-immigrant tide in this country that frightens me. It feeds on our depressed economy and is fueled by pervasive prejudices against people of color. The anti-immigrant law in Arizona epitomizes its ugly face, and elements of the right wing in this country are embracing the opportunity to assert a narcissistic frame on who is a “real American”.

What would my grandmother say?

Even though this country was founded by immigrants and shaped by the immigrant ethos — the notion of a safe haven — our history is also replete with contradictions, as manifested in the darker side of our past, namely Native American genocide and slavery. Let’s also not forget that even when slavery was abolished, women were second-class citizens in this nation.

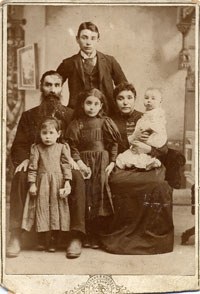

When I think of our nation’s history, I think about my own grandmother. She came on her own to this country from Hungary around 1890, traveling on a ship in a wave of Eastern European Jews who were looking for a better life on these shores. The details of her trip are a little fuzzy because she didn’t like to talk about “the past”. She even yelled at my grandfather one time when he started to tell me about his childhood in Hungary. “Saul! She doesn’t want to hear what happened so long ago!”, she snapped at him in her thick Eastern European accent, a comment I regret to this day.

We do know that my grandmother was only 13 years old when she arrived and like so many before and after her, she came through Ellis Island. She lived for a time in Manhattan with relatives who made the same journey. At some point, she got back on a boat and returned to Hungary, to bring her parents back with her. I imagine that by this point, she was fluent in English and that they spoke none. They lived in New York City, and through her teen years she became a skilled seamstress, working in sweatshops by day and studying clothing patterns by night so she could master the skill. She and my grandfather met in New York, where they opened a “dry goods” store, which apparently is a store that sells just about anything. She had, by then, become a master seamstress, and was also a mother of nine children, all of whom attended public schools and ultimately “made good”, achieving the American dream of sorts.

Of her nine children, there was one dentist, two English professors (including my father), a factory owner, an accountant, an architect, a schoolteacher, a bookkeeper and a postal worker. All but one had children of their own, 21 in all, and these children had over 20 children, and on and on it goes. With each successive generation, they are one step away from their heritage, and yet most have tried — in their own ways — to maintain a connection to their history.

How many people in America have some version of this story? Either they came to this country from foreign soil or the parents came or their grandparents came, to create a better life for themselves. They may have been fleeing political persecution or poverty or both. And when they came here, they struggled to learn the language, gain new skills, find jobs, and live the American dream. When they got to this country, they worked very, very hard. Many experienced discrimination, often from people who felt threatened by them in some way or wanted someone to be lower on the totem pole than them.

As Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, my grandparents were Caucasian. So while they experienced discrimination as Jews and as poor people, they didn’t experience discrimination because of the color of their skin.

When I hear about the anti-immigrant “movement”, I honestly feel sick. That must have something to do with my grandmother, as I think: Who are these people who hate people who are just arriving? Who are these people who want to close the borders? Who are these people who want to pass laws that allow English only? Who are these people who want to deny a college education to children of immigrants?

And what would their grandmothers say?

by Mindy Fried | Aug 4, 2010 | gardens, loss, memories

As the summer is hitting its peak, our garden is proliferating with cherry tomatoes, two different kinds of lettuce, green peppers, herbs and more… I can’t take credit for it, but I certainly do appreciate it! I’m also appreciating the increased interest across this country in local foods, eating healthy and the pinnacle of city gardens: farmers markets. It is VERY exciting that Boston will soon (1 1/2 years soon) have its own downtown farmers market, following in the footsteps of other cities like Philadelphia, Seattle and San Francisco.

But when I think of gardens and gardening, I am reminded of my cousin, an amazing gardener and gifted health care professional, who passed away over 3 years ago after struggling with lung cancer. Here is a poem that I wrote a couple years ago, following his untimely death…

Treatment stopped and powerful medicines eased the pain

So we sat on the porch on that crisp fall day

Atop the sloping hill, gazing at the garden below

Childlike in our wonder

Timeless in a moment of joy,

Feeling the warmth amidst the cool breeze

Wind chimes serenading us gently.

“Should I live another year”, you said,

“I’ll build a new bed

and get rid of those tall plants to let in more sun”.

Speaking quietly but resolutely,

as we sat on the porch on that crisp fall day.

Looking down at two tall grass-like reeds,

Surveying the garden and envisioning a valley of colorful abundance.

For the past two summers,

a cadre of family and friends have labored hard on this sacred land

Honoring your life and spirit with rakes and trowels, weeders and hoes,

Sprinkling the hills and valleys with greens, oranges and reds

that provide solid ground to your two young children.

Who grow stronger every day,

as they dig their fingers into rich, brown soil

that channels memories of their father through their tiny hands.

You had a plan when you surveyed the garden

from the porch on that crisp fall day

A moment of joy before things turned

The cool breeze and warm wind harmonizing

in a chorus of chimes and tears

Capturing a moment that continues to breathe

into that hallowed garden plot of land.