by Mindy Fried | Dec 8, 2015 | Black Lives Matter, black power, community, dance, diversity, inequality, Jewish identity, protest, race, racism, resilience, Ta Nahisi Coates

Here at the Mecca[1], under pain of selection, we have made a home. As do black people on summer blocks marked with needles, vials and hopscotch squares. As do black people dancing at rent parties, as do black people at their family reunions where we are regarded as survivors of catastrophe. As do black people toasting their cognac and German beers, passing their blunts and debating MCs. As do all of us who have voyaged through death, to life upon the shores.– Ta–Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me

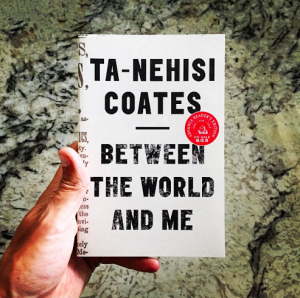

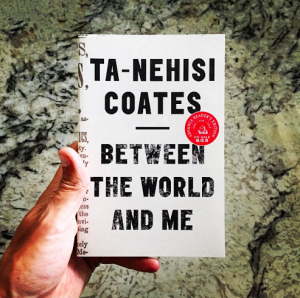

I just finished Ta–Nehisi Coates’ brilliant letter to his son. “I write you in your 15th year”, he says. “And you know now, if you did not before, that the police departments of your country have been endowed with the authority to destroy your body. . . I tell you now that the question of how one should live within a black body, within a country lost in the Dream, is the question of my life, and the pursuit of this question, I have found, ultimately answers itself.” I have only read this book once, and I know I will read it again; it is beautifully written and full of passionate insights. And it got me thinking about the black power movement that so deeply affected me in my late teens and twenties, and my first exposure to this movement, which arrived in a circuitous fashion that was quite personal.

In my freshman year of college, I was invited to join a sorority in which I was the only Jew. I discovered this fact when I was told, “You don’t look Jewish”, as if that were a compliment. For the first time, I felt that faintly uncomfortable sense of tokenism, knowing somehow that I was representing “my people”, but only because I fit in to “their” world. I’m sure that my response at the time was to smile, because I had been socialized that way. Perhaps it was a confused smile that attempted to cover up any latent anger doused with gratefulness for being accepted in this upper-class bastion where I did not belong. I continued to hang out with friends from my freshman dorm who had also joined the sorority, creating a transition to this new world as I walked a tight rope of social acceptance, wearing outside markers of belonging, with long flowing straight hair, short skirts and hip boots with heels. It all seemed so “natural”.

In my freshman year of college, I was invited to join a sorority in which I was the only Jew. I discovered this fact when I was told, “You don’t look Jewish”, as if that were a compliment. For the first time, I felt that faintly uncomfortable sense of tokenism, knowing somehow that I was representing “my people”, but only because I fit in to “their” world. I’m sure that my response at the time was to smile, because I had been socialized that way. Perhaps it was a confused smile that attempted to cover up any latent anger doused with gratefulness for being accepted in this upper-class bastion where I did not belong. I continued to hang out with friends from my freshman dorm who had also joined the sorority, creating a transition to this new world as I walked a tight rope of social acceptance, wearing outside markers of belonging, with long flowing straight hair, short skirts and hip boots with heels. It all seemed so “natural”.

The sorority was housed in a giant mansion where we “sisters” were invited to partake in formal dinners served by young college students whose lower class brought them to their jobs as “houseboys”, young men who were not allowed to enter through the front door, but came to work instead through the kitchen in the back of the house. This was not the South, as you might be imagining. This was Syracuse, New York in 1968. Meanwhile, I was having fun with my old friends from the dorm who had joined the sorority, and was excited about the prospect of sisterhood. Only occasionally was I feeling pangs of dissonance, despite my excitement about feeling welcomed. My parallel passion was dance, “my true home”, and I had jumped head first into the Dance Club at my university, because there was no dance major in those days. It was there that I found the greatest solace and a full spectrum of kindred spirits. The world of dance was a place that had always felt like home.

The sorority was housed in a giant mansion where we “sisters” were invited to partake in formal dinners served by young college students whose lower class brought them to their jobs as “houseboys”, young men who were not allowed to enter through the front door, but came to work instead through the kitchen in the back of the house. This was not the South, as you might be imagining. This was Syracuse, New York in 1968. Meanwhile, I was having fun with my old friends from the dorm who had joined the sorority, and was excited about the prospect of sisterhood. Only occasionally was I feeling pangs of dissonance, despite my excitement about feeling welcomed. My parallel passion was dance, “my true home”, and I had jumped head first into the Dance Club at my university, because there was no dance major in those days. It was there that I found the greatest solace and a full spectrum of kindred spirits. The world of dance was a place that had always felt like home.

After my first summer break, when I came back to college, I arrived at my new dorm excited to see my friends, and discovered that all of my friends from the sorority had moved into “the house” without letting me know their plans. Rather than feeling excluded at the time, I begged my parents to allow me to leave the dorm and move into “the house” as well. They agreed. Once settled in my new abode, I gradually allowed myself to see the real truth about the institution of which I had become a part. As a sister, I was part of a formal stratified system which included some and excluded many others. There were rules about behaving properly, including at three formal meals each day where we sat quietly and were served by the houseboys. Add to that the endless meetings which were governed by Roberts Rules of Order, further reinforcing the hierarchical stratification of our numbers. Hovering over our sisterhood was a small group of older women, den mothers of sorts who ensured this proper behavior. It was stifling, and this beautiful mansion began to feel like a prison.

young modern style dancer posing

My world outside was growing as I increasingly identified as a dancer, a creative soul who hung out with other artists who laughed freely, partook in group massage, and smoked weed. My best friend was a young gay man with a sharp eye and wit. Together we began to deconstruct the precious world of my sorority, finding absurdity in this bastion of the rich. As we absorbed the various social movements of the day, including a rising counterculture and a burgeoning civil rights movement, I had hopes that I could change the institution from within. I called for a meeting with the trustees of the sorority, and sitting in front of a small tribunal of the den mothers, I proposed that the sorority be transformed into a “collective”. Of course, they looked at me like the outcast that I was, their negative response confirming for me that this was a place where I – a Jew, an artist, a non-conformer – did not belong.

My parents gave me permission to move back into the dorm as long as I got a job to pay for my room and board. I got a job in a fast food joint, a precursor to McDonald’s, where you could get fired for pilfering one French fry. From the fancy sorority house, I moved into a simple dorm room – a double – which I shared with Cheryl, an African-American student from White Plains, New York, whose father was a psychiatrist and mother an accountant. My guess is that Cheryl didn’t have any say in the matter of my arrival, treating me cordially but with a cool distance. Each Sunday, my dancer friend and I would slip through the back door of “the house”, along with the houseboys, to pick up a delicious Sunday dinner – since my parents were still paying for the sorority through the semester. I was greeted by the lovely cook, who welcomed me with even more open arms now that I was no longer “in the fold”.

Over the few months that Cheryl and I shared a room, we developed a friendly-enough connection, but when the more radical “Harlem girls”, as they were called, came for a visit, Cheryl ignored me, and when I saw her outside of the room, she would not return my “hellos”. Eventually I moved out of the double and into a single room, and I’m sure my presence was not missed. I understood at the time that her lack of interest in me wasn’t personal, necessarily. This was a period in which black students on campus were building a movement of solidarity, separate from white people, even white roommates, and that this was an important moment of building confidence and connection amongst one another that didn’t include white women, even Jews who were rejected from Christian sororities. I remember feeling somewhat awed by the Harlem girls, who were beautiful and strong, and while Cheryl clearly came from a different class background from them, they all shared a special connection.

These were confusing times. I had gone from feeling like an outsider in the sorority because of my class and my Jewishness to being placed in the company of a young black woman who was an outsider, because of her race. Cheryl probably came from a “higher class” than me, but her racial background defined her in this predominantly white university setting, and the people she sought out for friendship were the Harlem girls, with whom she shared blackness, but not a class background.

In 1970, during my junior year, Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panther Party, came to campus to speak. By that time, my sorority days were far behind me, and I lined up with hundreds of students to get into a packed university chapel to hear him. I was blown away by his love of black people and his analysis of class-based hierarchies. I was struck by the power of celebrating one’s collective identity, as a way to build self-esteem, as a way to achieve solidarity with others, as a way to build a movement. Somehow, despite the fact that he was black and I am white, I felt that he was speaking to me, in his understanding of class divisions as well as racial divisions. I found myself a part of a group of white activists who supported the black power movement and Malcolm X., and felt that Martin Luther King was not radical enough. Of course now I see that the full spectrum of black leaders was necessary. But this was the early 1970s. My experience as a Jew who “passed” allowed me to understand tokenism, and my experience as a woman allowed me to better understand prejudice, being regarded as less than, not smart enough, not equal to…

In 1970, during my junior year, Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panther Party, came to campus to speak. By that time, my sorority days were far behind me, and I lined up with hundreds of students to get into a packed university chapel to hear him. I was blown away by his love of black people and his analysis of class-based hierarchies. I was struck by the power of celebrating one’s collective identity, as a way to build self-esteem, as a way to achieve solidarity with others, as a way to build a movement. Somehow, despite the fact that he was black and I am white, I felt that he was speaking to me, in his understanding of class divisions as well as racial divisions. I found myself a part of a group of white activists who supported the black power movement and Malcolm X., and felt that Martin Luther King was not radical enough. Of course now I see that the full spectrum of black leaders was necessary. But this was the early 1970s. My experience as a Jew who “passed” allowed me to understand tokenism, and my experience as a woman allowed me to better understand prejudice, being regarded as less than, not smart enough, not equal to…

As I read Ta–Nehisi Coates’ treatise to his son, I am reminded of the long and hard struggle of African-American people in this US of A. I reflect back on my earlier experience. We still live in a world of deep economic and social inequality and systemic racial injustice. I am appalled by some of the current insidious and frightening reactionary movements, fueled by politicians who take advantage of people – white people particularly – who are ignorant of possibilities and their own oppression. Sometimes I feel despairing, and yet there are places of light in the movement of people who are dedicated to social justice, people who fight for and support the current civil rights movement through Black Lives Matter, people who fight for survival on this planet through the climate change movement, people who fight for the rights of immigrants, following the line of so many people who have fought for acceptance in American society over hundreds of years, and people who continue to fight for women’s rights and LGBTQ rights. I think back to my old roommate Cheryl and the Harlem girls and wonder what they are thinking and doing today.

[1] Ta–Nehisi Coates refers to his alma mater Howard University, an historically black university, as the Mecca.

by Mindy Fried | Apr 14, 2015 | applied sociology, care child policy, diabetes, early education and care, gender, health care policy, policy, race, social class

My first job in Boston was working for Senator Jack Backman, a progressive state Senator who headed up the Human Services Committee on Families and Elder Affairs. I was considered his “child and family expert”, but I hardly felt like an expert, particularly in that shark tank of policymaking. I loved and hated that job, the daily tedious business of writing legislation, sitting for hours in meetings, taking orders as the lowest of the low on that totem pole. But I learned how to analyze a state budget, and how bills get passed, and who makes decisions behind which closed doors. I also learned that I wasn’t suited to moving things from inside the system, but I loved being an outsider trying to make the system move.

![]()

Senator Backman sponsored the first universal child care bill in the state, arguing that all children should have access to early childhood education. While this seems laudable now, at the time it was laughable because people felt it was so “out there”, beyond anything that was remotely possible. This was the early 80s, and while women had already been entering the labor force in droves, some politicians were just getting used to it.

![]()

The Governor, a rabid right-wing demagogue, vociferously argued against increasing child care subsidies to poor families, much less even considering universal child care policy. His famous line was that “child care is a Cadillac service”, a “luxury” that the state could not afford, particularly because it was women’s place to stay at home to care for their families. It took several decades for Massachusetts and 39 other states to finally implement universal pre-kindergarten (UPK).

The most compelling part of my job was working with a ferociously committed group of early childhood teachers who fought for more funding for child care programs, including funds to increase child care worker wages. Since my role was as a liaison to a liberal Senator, they lobbied me to take up their cause. Initially I felt flattered that they were trying to convince me to support their issues, but I soon realized that I was “one of them”, except that I had some leverage to help them get access to key legislators.

![]()

It was from this group of amazing early childhood education advocates that I learned about the need for government subsidies to defray the high cost of child care for low- and middle-income parents. It was from them that I learned about the high turnover of child care workers because of their low wages – and the negative impact of teacher turnover on the quality of care to children. Not too soon after I left that job, I became a lobbyist for a statewide child care association.

Recently, I organized a panel for the Sociologists for Women in Society winter meeting, and as I looked for speakers who could demonstrate the wide range of jobs that sociologists have in the “applied world”, I discovered Tekisha Everette, a brilliant Sociologist who, at the time, was working as a lobbyist with the American Diabetes Association. Tekisha spoke about why she chose to be an Applied Sociologist, the substance of what she actually does in her job on a day-to-day basis as a lobbyist, and how she incorporates a race/gender/class lens in talking with policymakers about public health issues. Having worked in the policy world, I was particularly moved by how Tekisha uses her scholarship as a sociologist, incorporating analyses of how race, gender and class affect public health policy issues. Here’s a snippet of our conversation:

![]()

Mindy: Tekisha – why did you choose to do Applied Sociology?

Tekisha: I chose Applied Sociology because I wanted to combine my educational background – political science, policy and sociology – to affect change in society. I wanted to go beyond studying society to applying that knowledge to drive policy change in society.

M: Can you tell me a bit about the types of applied jobs you have held?

T: I am a lobbyist now but I’ve been policy analyst and a liaison between state government employees and a firm of economists. In each position, I have used my research skills as well as my sociological theoretical lens to execute my work. For me, this has been an amazing experience because I am relevant in a variety of spaces and I can alter my voice and perspective based on what is needed in the situation.

M: How would you describe the role you play within the organization’s structure?

T: I am the lead lobbyist for my organization and I lead a team of three lobbyists and one manager. I provide strategic leadership on policy and legislative efforts of the Association. I also serve as a member of senior management for the department and help shape a number of our projects and priorities. Since most, if not all, of our initiatives have to be evidence-based, I spend a fair amount of time reviewing, requesting, and explaining research to support our legislative ideas.

M: What does the work of a lobbyist entail?

T: Interacting with Members of Congress and their staff, the White House and federal agencies, training and helping our advocates to use their experience to gain support for legislative proposals, reading/reviewing research and translating it into policy.

M: How do you incorporate a sociological lens in your work?

T: Since I have come to my organization, there have been a number of times where I’ve been able to bring a sociological lens to affect decision-making. Overall, I think I have worked to change the way we make decisions to ensure that we take a variety of backgrounds and various interests into account. Being a sociologist gives me the advantage of being able to go beyond the data and making it relevant to policymakers in ways they can understand. My goal is to always be sure I can explain the impact of policy at a localized level – and to incorporate the impact from a gender, race and class perspective.

M: What drives you to do this work?

T: I believe that you have to be a able to explain anything you do to your grandma! Perfecting the art of being able to use research and explain it to a variety of audiences is important to me.

Tekisha has just accepted a new position to become the inaugural Executive Director of Health Equity Solutions in Connecticut. The organization is a non-profit focused on addressing health equity issues in Connecticut through public policy, education and advocacy activities. She begins her new position in May, as she takes on another opportunity to have an impact in the policy arena!

by Mindy Fried | Apr 1, 2015 | adventure, applied sociology, careers, finding work, gender, making choices, program evaluation, race, social science research, sociology

When attempting to transform communities through social policy, it is imperative to not only understand what the social problem is, but also how and why it exists and persists. Trained sociologists have indispensable tools for this type of applied work. – Chantal Hailey

In my last blog post – Choosing Applied Sociology – I referred to a 2013 article in Inside Higher Ed in which Sociologist Roberta Spalter-Roth, from the American Sociological Association, comments that “In sociology, there is close to a perfect match between available jobs and new Ph.D.s”, if you take into account non-academic jobs (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/08/06/sociology-job-market-continues-recover-steadily). She notes that while these “applied” jobs often pay more than university teaching positions, graduates rarely know about them and professors may even discourage their students from entering these professions.

Unfortunately, the majority of Sociology grad students view the tenure-track job market as their only career choice, but there are many Sociologists who have chosen to work in applied settings. The skills gleaned through a Sociology degree are applicable – or dare I say, “marketable” – in a whole host of other venues, including government, corporations, and all sizes of nonprofits, local, state and national. We are researchers, lobbyists, program managers, teachers/trainers, and more.

![]()

I decided to organize a panel on this topic at the annual meeting of Sociologists for Women in Society, held in Washington, DC. And on February, 2015, three distinguished Applied Sociologists from the DC area presented about why they chose this route of practice, what they do and for which populations, and how they incorporate sociological principles into their work, framed by a race, class, gender lens. In this post, one of the speakers, Chantal Hailey, talks about her draw to applied work, which she began as a Sociology student at Howard University. After a number of years doing Applied Sociology, Chantal is now a first year doctoral student at New York University.

Mindy: What interested you in doing applied work?

Chantal: Throughout out my childhood, I lived, attended summer camps and had friends and family who lived in low-income urban neighborhoods. I was able to see how low-quality schools, subpar housing, limited opportunities and violence shaped young peoples’ lives and limited their potential. I had a passion to transform these communities into places where all people could thrive. But on the other hand, I was a nerd. I enjoyed research, history, math and statistics.

During my internship at a research branch of a community development corporation, I discovered that providing statistical trends on health, education, and housing to nonprofits could help them inform how they served low-income communities. I also discovered that the voices of women and people of color were sometimes absent from these discussions. I knew that in order to get a seat at the table, as a black woman, I needed to have the highest credential possible. So I began my academic journey at Howard University (as an) undergraduate in the Sociology department, knowing that my ultimate goal was to complete a doctoral degree in Sociology.

Mindy: Did you know you were learning about Applied Sociology at that point?

Chantal: While I was at Howard, I didn’t know of any distinction between applied and “pure” sociology. I just completed papers on topics that were important to me–public housing, poverty, and education. Urban Institute (UI) kept popping up in my literature reviews and I applied for internship there after my junior year.

Mindy: What did you do when you were at Urban Institute?

Chantal: At Urban Institute (UI), I transformed from an intern to a Research Assistant to a Research Associate. UI’s research is a combination of researcher-generated projects and responses to RFPs (Requests for Proposals). Two of my projects exemplify the type of applied sociology I was able to undertake at UI. The first is the “Long Term Outcomes for Chicago Public Housing Families” project (LTO). LTO is a 10-year longitudinal study of families whose Chicago public housing was demolished or revitalized through the Plan for Transformation. We employed mixed methodology – family surveys; in-depth interviews with heads of household, young adults and children; and administrative data review.

We found that after relocation from distressed public housing developments, families generally lived in better quality housing in safer neighborhoods, but many adults struggled with physical illnesses and youth suffered the consequences of chronic neighborhood violence.

Mindy: What was your role there? What did you do?

Chantal: As a team member in this project, I assisted in developing the survey, helped lead data analysis, generated the young adult interview guides and conducted in-depth interviews with the young people in the study. I also co-led and lead-authored research briefs on housing and neighborhood quality and youth. A research brief is a 15-20 page synopsis of research findings. Unlike most journal articles, there is not a long literature review.

This short article allows us to disseminate the findings to wide audiences. In addition to the standard research brief, we also produced blogs, HUD online journal articles, and radio reports; and briefed the Chicago Housing Authority, Senate committee members, and the press. LTO used sociological methods to understand policy, but intentionally shared this knowledge with wider policy makers and practitioners.

Mindy: You say that trained Sociologists have “indispensable tools” for applied sociology. Can you elaborate on this a bit?

Chantal: Sociology can address a plethora of subject areas that often intersect (i.e. inequality, education, crime and violence, health, etc.), and it unveils the mechanisms behind social problems. A Sociology education trains researchers to look for the hidden transcripts among social groups and interactions, not just the most apparent narrative. It allows for simultaneous macro, meso, and micro analysis to understand multiple contributing factors. And it emphasizes the impact social context has on policies’ implementation and outcomes.

This was especially apparent in the LTO study. We understood that in addition to families’ relocation from public housing, a series of key factors – including proliferating national rates of housing foreclosure, increasing Chicago neighborhood violence, and rising income inequality – also shaped families’ experiences in South Side Chicago neighborhoods.

A Sociology education provides an array of methodological tools that can be tailored to best address research questions (i.e. interviews, focus groups, ethnography, quantitative analysis). It pairs theories of race, class, family structure, etc. to better understand social issues. These analytic and research skills allow us to partner with government, non-profit, and academic agencies to both advance sociological theory and offer practical solutions to social problems.

Mindy: Thank you! And can you provide another example of applied work you’ve done, where you’ve been able to bring your analytic and research skills to the fore?

Chantal: In D.C., I participated in a Community Based Participatory Grant funded by NIH entitled Promoting Adolescent Sexual Safety (PASS). UI, University of California San Diego, D.C. Housing Authority, and D.C. public housing residents collaborated in the PASS project.

This research team – along with a mix of individuals from different racial, class, and professional backgrounds – aimed to develop a program to increase sexual health and decrease sexual violence.

Mindy: How did you use what you were learning as a Sociology student/practitioner?

Chantal: Again, we used sociological methods to conduct this project, including an adult and youth survey, in-depth interviews with community members, participant observations, and focus groups.

Mindy: You said this project was participatory. Can you talk about who was involved? How was it participatory?

Chantal: Through the grant, we developed a community advisory board, a group of 15 residents who participated in creating the PASS program. The interactions between the community advisory board, community practitioners, and the researchers challenged the researchers to not only study educational, class, geographic and racial inequalities, but also to assess how our interactions dismantled or exacerbated power inequities.

Mindy: Earlier, when we spoke, you talked about what it was like to be an African-American researcher who also had a personal understanding of the experience of people you were researching. Can you talk a little about that?

Chantal: As an African American woman on the project with family who lived in D.C., I was personally challenged to both create distance as a researcher and closeness as a fellow black D.C. resident. I often found myself “code-switching” during community meetings, as I communicated with both my co-workers and the community members. Feeling a responsibility to and, often, sympathizing with the desires of the researchers and the residents, I also had to sometimes explain and mediate diverging understandings during conflicts. This closeness and distance dichotomy was also pertinent during data analysis. While my experiences allowed me to recognize and interpret focus group participants’ terminologies and cultural cues, I had to ensure that my sympathies with the community did not cloud my ability to see inconvenient truths.

Mindy: And how did you get what you learned out there to your target audiences?

Chantal: This research project, like most UI projects, focused on dissemination to wider audiences in palatable formats–a community data walk, research briefs, blogs and journal articles.

Mindy: Finally…now you’re a doctoral student at NYU and studying Sociology. How do you see yourself moving forward as a Sociologist? How will you incorporate what you’ve learned into your future practice? (or is that something you’re still figuring out!)

Chantal: As I continue in graduate school at NYU, I aim to crystalize my research identity and trajectory. I have methodological and policy research experience through the Urban Institute, and I am gaining theoretical expertise while completing my doctoral degree. I hope to incorporate these elements into my research and become a conduit between academia, policy makers, and urban communities to make inner city neighborhoods a place where all children can thrive. A mentor once advised me that graduate school is a journey where you begin in one place and end in another. I am tooled with amazing applied experiences and I’m excited to see how my graduate school journey directs my path.

by Mindy Fried | Mar 25, 2015 | applied sociology, gender, program evaluation, race, selecting evaluation researcher, social class, social justice, social science research, working with evaluation researcher

![]()

After working in the policy world in Massachusetts for many years, going back to graduate school in Sociology felt like going to a candy store in the country* every day, where I could read interesting books, have stimulating conversations, learn how to do research, and then write about it. I admired my professors, and I was kind of amazed that their job was to take me seriously and support my development as a scholar. Later, while I was working on my dissertation, I got a job teaching part-time in a local university while a full-time professor went out on leave. It was challenging; it was fun; and it was an incredible opportunity to experiment with pedagogy. I learned that I loved teaching, and over the next two years, got hired to teach a wide range of sociology classes – about families, sex and gender, feminism, work, and women and leadership – at several other Boston universities.

![]()

But the more I learned about the full-time tenure-track teaching world, the more I realized it was just not my thing. First off, I couldn’t imagine “starting over” again at the bottom of the career ladder, with what could be six grueling years of slogging towards tenure. Nor could I imagine the idea of a job for life – the promise of tenure – working with the same folks for the next few decades (apologies to my mythical could-have-been colleagues!). Call me fickle, but I enjoyed changing jobs every few years, having new and varied challenges, and working with a diverse array of people.

Learning on the job

By luck, while I was taking research methods classes, I was offered a small consulting job to evaluate the impact of a well-established training program on its activist participants. Here was an opportunity to put my newfound knowledge to use. Except that no one was teaching how to evaluate social programs in sociology graduate programs! I did have some experience with “program evaluation”. When I was directing a statewide child care project that was federally funded, some guy was hired by the state to evaluate my program. He met with me once at the beginning of the project, and at the end, he wrote a glowing report.

![]()

Every so often, I wondered if he’d be back. In the end, he really had no basis upon which to evaluate the strengths and challenges the project was facing – and believe me, there were plenty. But I wasn’t going to complain if he was phoning it in!

Since I had no idea how to evaluate a program, I hired someone who did, and for the next few years, she trained me and my sociologist friend, Claire, in how to use research skills to evaluate social programs. I never intended to continue doing this “applied” work for the next 20 years, but that is essentially what has happened. When I first started, I wasn’t very good at it, and I thought it was boring. But a couple decades later, I have learned a whole lot about how to do it well, and (luckily) find this work fascinating.

Making a choice to be an applied sociologist

The choice to be an “applied sociologist” is not a rejection or devaluation of academic sociology. It is a choice that is, in part, a function of economic imperatives – a tight job market, especially if you don’t want to move – but also a choice to make a different kind of difference. To impact the social world through organizations that are impacting people: through service, through organizing, and through education and advocacy, in the areas of public health, education, urban planning, climate change, arts and arts education and many more.

I have learned that it makes me happy to use the research and writing skills I learned in graduate school as a tool to help promote social change, through the vehicle of strengthening nonprofit organizations and improving philanthropic decision-making. Once considered the stepchild of the field, applied sociology is now gaining prominence, but largely because the economy has not produced the plethora of academic sociology jobs once predicted.

“Close to a perfect match”

In a 2013 article in Inside Higher Ed, Roberta Spalter-Roth, from the American Sociological Association, commented that “In sociology, there is close to a perfect match between available jobs and new Ph.D.s” (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/08/06/sociology-job-market-continues-recover-steadily). But this is only if you factor in the many government, nonprofit and research analyst jobs out there that require the skills and sociological perspectives learned in graduate school. Spalter-Roth notes that these jobs often pay more than university teaching positions, but graduates rarely know about them and professors may even discourage their students from entering these professions.

This year, my applied sociology friends and I agree that the “applied route” seems to be gaining some traction, with increased interest from universities and professional associations. A number of us have been on a (minor) speaking circuit, talking to graduate students at the request of sociology departments about choosing applied sociology as a career. And this year, the Sociology Department of a major research university, Boston College, hired me to teach a course on Evaluation Research. (Kudos to BC Sociology for recognizing the importance of this avenue for sociologists-in-training!)

Panel at Sociologists for Women in Society: Choosing Applied Sociology (sponsored by the Career Development Committee)

Given this increased interest, and what I believe is a need for sociologists to promote the health and well-being of organizations and communities using research and sociological principles, I organized a panel on this topic at an annual meeting of my favorite national feminist sociology organization, Sociologists for Women in Society.

The panel included three distinguished applied sociologists from the DC area, where the meeting was held, who presented about why they chose this route of practice, what they do and for what populations, and how they incorporate sociological principles into their work, framed by a race, class, gender lens.

The speakers, all based in DC, included Tekisha Everette, a lobbyist for the American Diabetes Association; Andrea Robles, a research analyst at the Corporation for National and Community Service; and Chantal Hailey, who ran evaluation projects at the national Urban Institute and elsewhere, and is currently a sociology doctoral student at NYU. One other panelist, Rita Stephens, was not able to make it because of a blasted snowstorm, but she would have rounded out the panel very nicely as she works at the State Department. The three women spoke to a standing and sitting room only crowd at the meeting, followed by numerous informal conversations, attesting to the fact that there is a hunger for this kind of work.

In my next couple of blog posts, I will allow these amazing women’s words speak for themselves. I hope that their words stimulate a dialogue about the value of and choice to pursue sociology outside of the academy. Based on the remarkable response at this meeting and in classrooms where I talk about applied sociology, my sense is that sociologists want to know about alternatives to working within academia. The words of these speakers inspired me and I hope they inspire you.

“I was interested in doing applied work that could lead to positive social

change. Somehow, it seemed like I wanted to be part of making the world

a better place.”

Sociologist, Andrea Robles

Corporation for National and Community Service

Check out this excellent blog post by Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, Research and Social Media Consultant with Social Science Insights in Australia, called What is Applied Sociology?, published in Sociology at Work: Working for Social Change: http://sociologyatwork.org/about/what-is-applied-sociology/

*Brandeis University, which is actually in the suburb of Waltham, Massachusetts, but looked like the country to this city girl!

by Mindy Fried | Feb 12, 2013 | conservatives, ethnicity, G.O.P., gender, health, health care, inequality, progressive policies, race, Republicans, social class, social policy, social science research

The American Enterprise Institute just published a speech by G.O.P. darling and House Majority Leader, Eric Cantor, in which he calls for cutting all federal funds for social science research, insisting that the money would be better spent finding cures to diseases. He uses the story of a child named Katie who battled cancer, and who “just happened” to be sitting in the front row of his audience. “Katie became a part of my congressional office’s family and even interned with us”, he is quoted as saying. “We rooted for her, and prayed for her. Today, she is a bright 12-year-old that is making her own life work despite ongoing challenges…Katie, thank you for being here with us”.

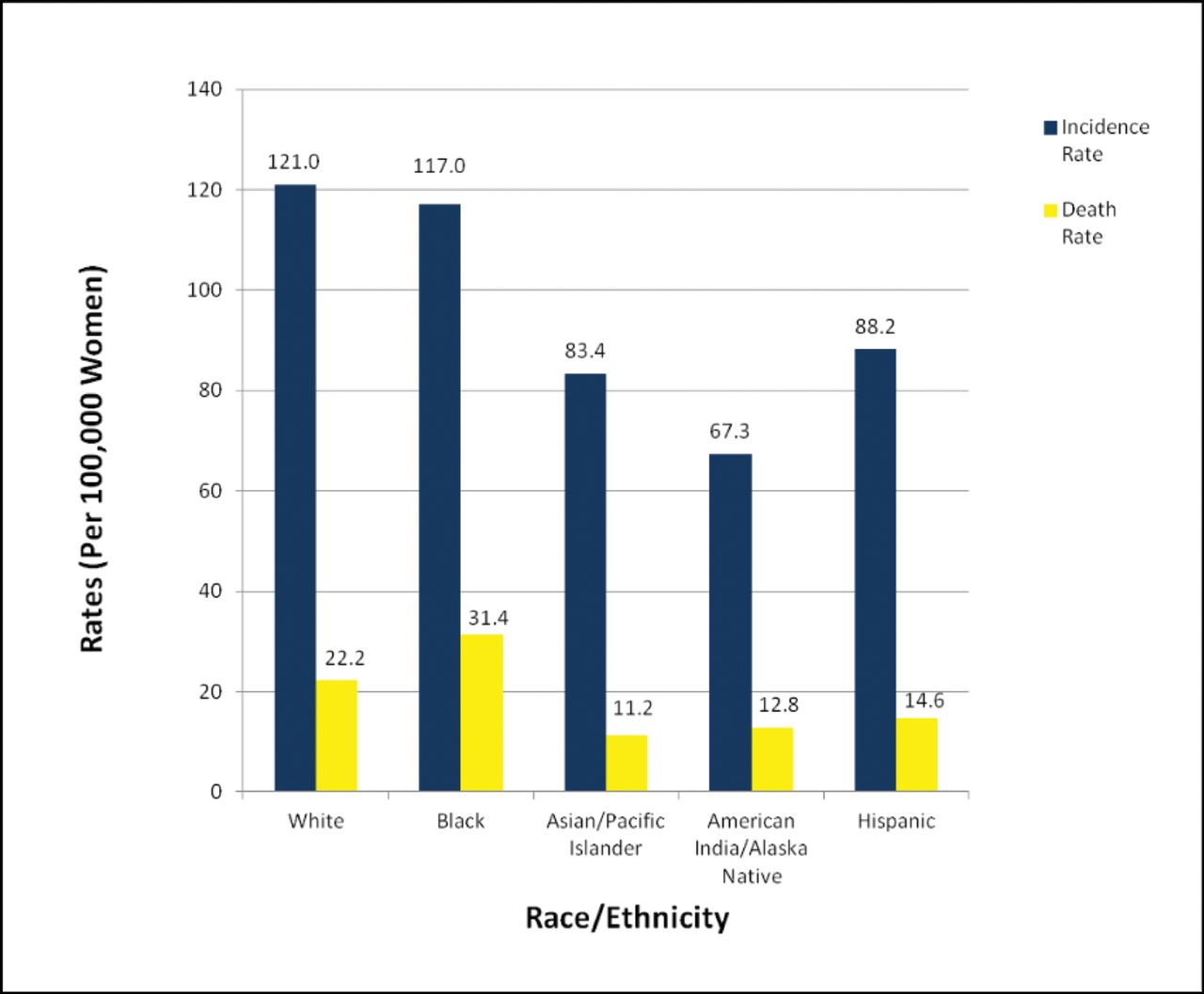

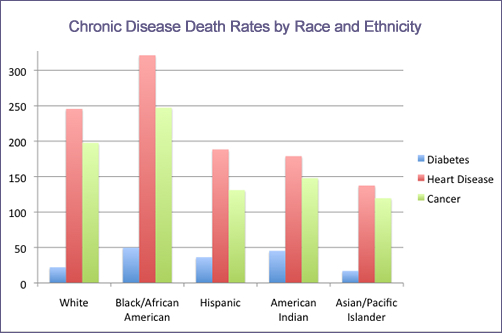

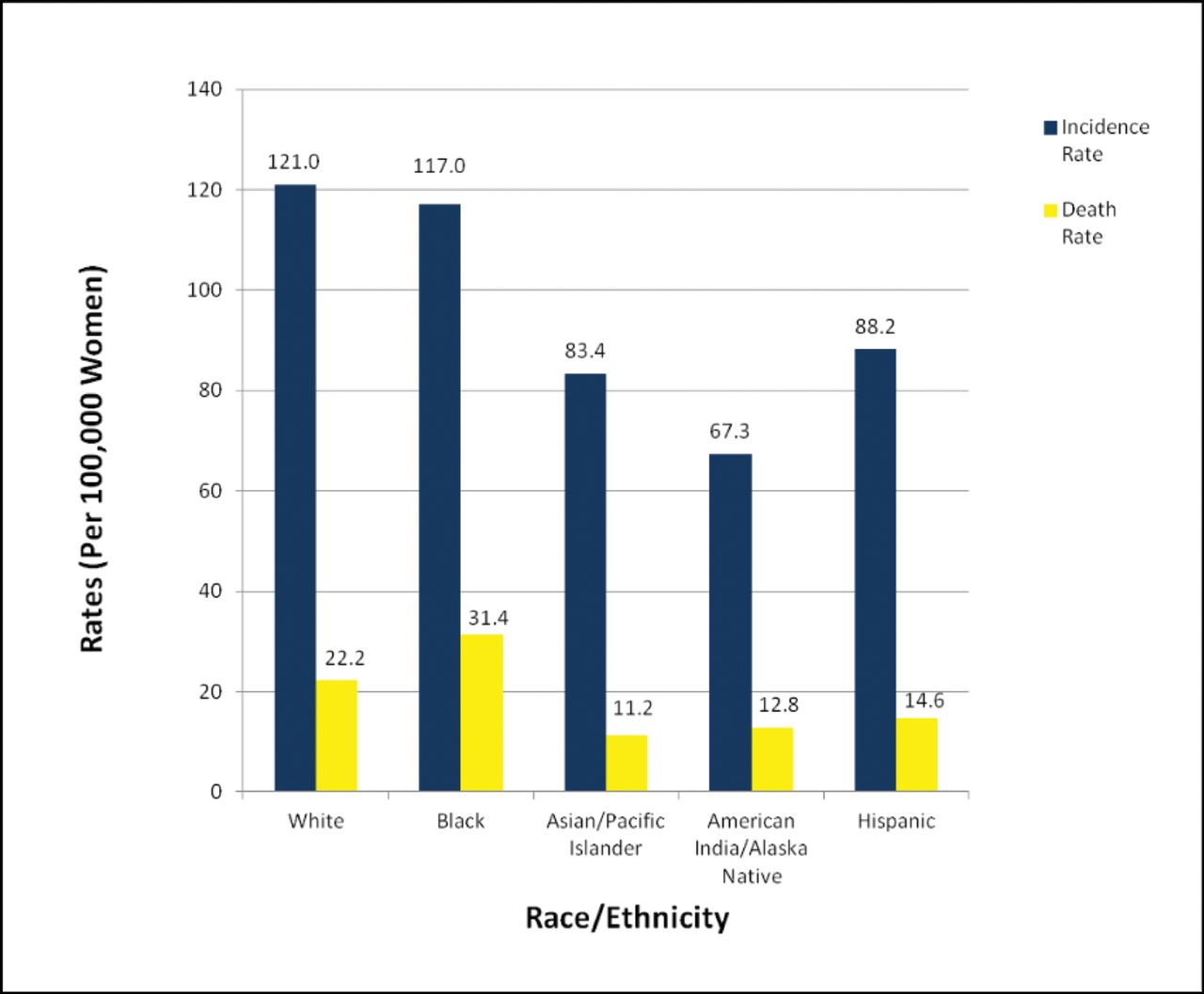

(Please note that the graphic visualizations in this post illustrate the importance of information generated through social science research which have critical implications for policy, e.g., the disproportionate impact of poverty on health outcomes by race/ethnicity) .

I can imagine the emotions in that room, as the audience learns that Katie’s disease is now in remission. Some people of faith in the crowd might be thinking that prayers led to the improvement in her health. But Cantor does not invoke divine intervention. Nor does he totally discount the role that publicly funded resources may have played in helping restore Katie’s health. On the contrary, he cannily declares that there is “an appropriate and necessary role for the federal government to ensure funding for basic medical research. Doing all we can to facilitate medical breakthroughs for people like Katie should be a priority. We can and must do better”.

But investing more public funds in research on medical cures, says Cantor, would require cuts in funding for social science research. Presumably, his argument is in the interests of budgetary discipline, because it makes no sense if the goal is to improve people’s health. Less social science research dollars will only weaken our capacity to understand the critical link between the social determinants of disease and health outcomes. We need to ask: Why did Katie get sick? Was she living near a power plant or did she go to a “sick school”? What kinds of services did she have access to? What is Katie’s ethnic/racial background? What is her class background? Because chances are, if Katie is white and middle-class, her access to services are better than if she’s black or Latino and poor.

Cantor trots out the familiar conservative template: We need policies that are based on “self-reliance, faith in the individual, trust in the family and accountability in government”. He declares that the House Majority – aka Republicans – “will pursue an agenda based on a shared vision of creating the conditions for health, happiness, and prosperity for more Americans and their families. And to restrain Washington from interfering in those pursuits”.

But while Cantor frames this as a message of empowerment, his solutions will only reproduce and expand poverty and inequality. Self-reliance is code for slashing government funding. Restraining Washington from interfering with health and prosperity will mean reducing taxes for the rich. And cutting social science research will eliminate needed publicly-funded analyses that provide an essential critique of social and economic policies and their impact.

Cantor’s stance is calculated to appeal to people who are struggling in a tough economy. In his speech, he argues that in America, where two bicycle mechanics, the Wright Brothers, “gave mankind the gift of flight”, we have the power to overcome adversity. “That’s who we are”, he says. Moreover, he argues that throughout history, “children were largely consigned to the same station in life as their parents. But not here. In America, the son of a shoe salesman can grow up to be president. In America, the daughter of a poor single mother can grow up to own her own television network. In America, the grandson of poor immigrants who fled religious persecution in Russia can become the majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives”.

All I can say is, sign me up, Eric! I’m the grand-daughter of a Russian immigrant, and maybe I’d like to become the majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives! Honestly? I get weary when I hear about the American dream from another rich, white guy who points to exceptions to the rule, and cynically tries to generalize them.

I just came back from a four-day feminist sociology meeting, sponsored by the organization, Sociologists for Women in Society (SWS) http://www.socwomen.org/web/, in which 250 scholars from around the U.S. and beyond, shared their research about how gender, race and class affect power and status, and how these determinants affect the realities of people’s lives – including their access to quality health care, decent jobs with benefits, high quality education, freedom from discrimination, and safe environments. These are the conditions that Cantor claims should be the right of all Americans, and yet his agenda makes them all less achievable. If Eric Cantor had been at that conference for just one hour, he would have heard about the importance of social science research in understanding systems that reproduce disadvantage for low-income people, immigrants, people of color, same-sex couples and more… But maybe if you preach self-reliance, limited government involvement, and the power of prayer, even a group of brilliant social scientists won’t change your mind.

In my freshman year of college, I was invited to join a sorority in which I was the only Jew. I discovered this fact when I was told, “You don’t look Jewish”, as if that were a compliment. For the first time, I felt that faintly uncomfortable sense of tokenism, knowing somehow that I was representing “my people”, but only because I fit in to “their” world. I’m sure that my response at the time was to smile, because I had been socialized that way. Perhaps it was a confused smile that attempted to cover up any latent anger doused with gratefulness for being accepted in this upper-class bastion where I did not belong. I continued to hang out with friends from my freshman dorm who had also joined the sorority, creating a transition to this new world as I walked a tight rope of social acceptance, wearing outside markers of belonging, with long flowing straight hair, short skirts and hip boots with heels. It all seemed so “natural”.

In my freshman year of college, I was invited to join a sorority in which I was the only Jew. I discovered this fact when I was told, “You don’t look Jewish”, as if that were a compliment. For the first time, I felt that faintly uncomfortable sense of tokenism, knowing somehow that I was representing “my people”, but only because I fit in to “their” world. I’m sure that my response at the time was to smile, because I had been socialized that way. Perhaps it was a confused smile that attempted to cover up any latent anger doused with gratefulness for being accepted in this upper-class bastion where I did not belong. I continued to hang out with friends from my freshman dorm who had also joined the sorority, creating a transition to this new world as I walked a tight rope of social acceptance, wearing outside markers of belonging, with long flowing straight hair, short skirts and hip boots with heels. It all seemed so “natural”. The sorority was housed in a giant mansion where we “sisters” were invited to partake in formal dinners served by young college students whose lower class brought them to their jobs as “houseboys”, young men who were not allowed to enter through the front door, but came to work instead through the kitchen in the back of the house. This was not the South, as you might be imagining. This was Syracuse, New York in 1968. Meanwhile, I was having fun with my old friends from the dorm who had joined the sorority, and was excited about the prospect of sisterhood. Only occasionally was I feeling pangs of dissonance, despite my excitement about feeling welcomed. My parallel passion was dance, “my true home”, and I had jumped head first into the Dance Club at my university, because there was no dance major in those days. It was there that I found the greatest solace and a full spectrum of kindred spirits. The world of dance was a place that had always felt like home.

The sorority was housed in a giant mansion where we “sisters” were invited to partake in formal dinners served by young college students whose lower class brought them to their jobs as “houseboys”, young men who were not allowed to enter through the front door, but came to work instead through the kitchen in the back of the house. This was not the South, as you might be imagining. This was Syracuse, New York in 1968. Meanwhile, I was having fun with my old friends from the dorm who had joined the sorority, and was excited about the prospect of sisterhood. Only occasionally was I feeling pangs of dissonance, despite my excitement about feeling welcomed. My parallel passion was dance, “my true home”, and I had jumped head first into the Dance Club at my university, because there was no dance major in those days. It was there that I found the greatest solace and a full spectrum of kindred spirits. The world of dance was a place that had always felt like home.

In 1970, during my junior year, Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panther Party, came to campus to speak. By that time, my sorority days were far behind me, and I lined up with hundreds of students to get into a packed university chapel to hear him. I was blown away by his love of black people and his analysis of class-based hierarchies. I was struck by the power of celebrating one’s collective identity, as a way to build self-esteem, as a way to achieve solidarity with others, as a way to build a movement. Somehow, despite the fact that he was black and I am white, I felt that he was speaking to me, in his understanding of class divisions as well as racial divisions. I found myself a part of a group of white activists who supported the black power movement and Malcolm X., and felt that Martin Luther King was not radical enough. Of course now I see that the full spectrum of black leaders was necessary. But this was the early 1970s. My experience as a Jew who “passed” allowed me to understand tokenism, and my experience as a woman allowed me to better understand prejudice, being regarded as less than, not smart enough, not equal to…

In 1970, during my junior year, Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panther Party, came to campus to speak. By that time, my sorority days were far behind me, and I lined up with hundreds of students to get into a packed university chapel to hear him. I was blown away by his love of black people and his analysis of class-based hierarchies. I was struck by the power of celebrating one’s collective identity, as a way to build self-esteem, as a way to achieve solidarity with others, as a way to build a movement. Somehow, despite the fact that he was black and I am white, I felt that he was speaking to me, in his understanding of class divisions as well as racial divisions. I found myself a part of a group of white activists who supported the black power movement and Malcolm X., and felt that Martin Luther King was not radical enough. Of course now I see that the full spectrum of black leaders was necessary. But this was the early 1970s. My experience as a Jew who “passed” allowed me to understand tokenism, and my experience as a woman allowed me to better understand prejudice, being regarded as less than, not smart enough, not equal to…