by Mindy Fried | Apr 14, 2015 | applied sociology, care child policy, diabetes, early education and care, gender, health care policy, policy, race, social class

My first job in Boston was working for Senator Jack Backman, a progressive state Senator who headed up the Human Services Committee on Families and Elder Affairs. I was considered his “child and family expert”, but I hardly felt like an expert, particularly in that shark tank of policymaking. I loved and hated that job, the daily tedious business of writing legislation, sitting for hours in meetings, taking orders as the lowest of the low on that totem pole. But I learned how to analyze a state budget, and how bills get passed, and who makes decisions behind which closed doors. I also learned that I wasn’t suited to moving things from inside the system, but I loved being an outsider trying to make the system move.

![]()

Senator Backman sponsored the first universal child care bill in the state, arguing that all children should have access to early childhood education. While this seems laudable now, at the time it was laughable because people felt it was so “out there”, beyond anything that was remotely possible. This was the early 80s, and while women had already been entering the labor force in droves, some politicians were just getting used to it.

![]()

The Governor, a rabid right-wing demagogue, vociferously argued against increasing child care subsidies to poor families, much less even considering universal child care policy. His famous line was that “child care is a Cadillac service”, a “luxury” that the state could not afford, particularly because it was women’s place to stay at home to care for their families. It took several decades for Massachusetts and 39 other states to finally implement universal pre-kindergarten (UPK).

The most compelling part of my job was working with a ferociously committed group of early childhood teachers who fought for more funding for child care programs, including funds to increase child care worker wages. Since my role was as a liaison to a liberal Senator, they lobbied me to take up their cause. Initially I felt flattered that they were trying to convince me to support their issues, but I soon realized that I was “one of them”, except that I had some leverage to help them get access to key legislators.

![]()

It was from this group of amazing early childhood education advocates that I learned about the need for government subsidies to defray the high cost of child care for low- and middle-income parents. It was from them that I learned about the high turnover of child care workers because of their low wages – and the negative impact of teacher turnover on the quality of care to children. Not too soon after I left that job, I became a lobbyist for a statewide child care association.

Recently, I organized a panel for the Sociologists for Women in Society winter meeting, and as I looked for speakers who could demonstrate the wide range of jobs that sociologists have in the “applied world”, I discovered Tekisha Everette, a brilliant Sociologist who, at the time, was working as a lobbyist with the American Diabetes Association. Tekisha spoke about why she chose to be an Applied Sociologist, the substance of what she actually does in her job on a day-to-day basis as a lobbyist, and how she incorporates a race/gender/class lens in talking with policymakers about public health issues. Having worked in the policy world, I was particularly moved by how Tekisha uses her scholarship as a sociologist, incorporating analyses of how race, gender and class affect public health policy issues. Here’s a snippet of our conversation:

![]()

Mindy: Tekisha – why did you choose to do Applied Sociology?

Tekisha: I chose Applied Sociology because I wanted to combine my educational background – political science, policy and sociology – to affect change in society. I wanted to go beyond studying society to applying that knowledge to drive policy change in society.

M: Can you tell me a bit about the types of applied jobs you have held?

T: I am a lobbyist now but I’ve been policy analyst and a liaison between state government employees and a firm of economists. In each position, I have used my research skills as well as my sociological theoretical lens to execute my work. For me, this has been an amazing experience because I am relevant in a variety of spaces and I can alter my voice and perspective based on what is needed in the situation.

M: How would you describe the role you play within the organization’s structure?

T: I am the lead lobbyist for my organization and I lead a team of three lobbyists and one manager. I provide strategic leadership on policy and legislative efforts of the Association. I also serve as a member of senior management for the department and help shape a number of our projects and priorities. Since most, if not all, of our initiatives have to be evidence-based, I spend a fair amount of time reviewing, requesting, and explaining research to support our legislative ideas.

M: What does the work of a lobbyist entail?

T: Interacting with Members of Congress and their staff, the White House and federal agencies, training and helping our advocates to use their experience to gain support for legislative proposals, reading/reviewing research and translating it into policy.

M: How do you incorporate a sociological lens in your work?

T: Since I have come to my organization, there have been a number of times where I’ve been able to bring a sociological lens to affect decision-making. Overall, I think I have worked to change the way we make decisions to ensure that we take a variety of backgrounds and various interests into account. Being a sociologist gives me the advantage of being able to go beyond the data and making it relevant to policymakers in ways they can understand. My goal is to always be sure I can explain the impact of policy at a localized level – and to incorporate the impact from a gender, race and class perspective.

M: What drives you to do this work?

T: I believe that you have to be a able to explain anything you do to your grandma! Perfecting the art of being able to use research and explain it to a variety of audiences is important to me.

Tekisha has just accepted a new position to become the inaugural Executive Director of Health Equity Solutions in Connecticut. The organization is a non-profit focused on addressing health equity issues in Connecticut through public policy, education and advocacy activities. She begins her new position in May, as she takes on another opportunity to have an impact in the policy arena!

by Mindy Fried | Mar 25, 2015 | applied sociology, gender, program evaluation, race, selecting evaluation researcher, social class, social justice, social science research, working with evaluation researcher

![]()

After working in the policy world in Massachusetts for many years, going back to graduate school in Sociology felt like going to a candy store in the country* every day, where I could read interesting books, have stimulating conversations, learn how to do research, and then write about it. I admired my professors, and I was kind of amazed that their job was to take me seriously and support my development as a scholar. Later, while I was working on my dissertation, I got a job teaching part-time in a local university while a full-time professor went out on leave. It was challenging; it was fun; and it was an incredible opportunity to experiment with pedagogy. I learned that I loved teaching, and over the next two years, got hired to teach a wide range of sociology classes – about families, sex and gender, feminism, work, and women and leadership – at several other Boston universities.

![]()

But the more I learned about the full-time tenure-track teaching world, the more I realized it was just not my thing. First off, I couldn’t imagine “starting over” again at the bottom of the career ladder, with what could be six grueling years of slogging towards tenure. Nor could I imagine the idea of a job for life – the promise of tenure – working with the same folks for the next few decades (apologies to my mythical could-have-been colleagues!). Call me fickle, but I enjoyed changing jobs every few years, having new and varied challenges, and working with a diverse array of people.

Learning on the job

By luck, while I was taking research methods classes, I was offered a small consulting job to evaluate the impact of a well-established training program on its activist participants. Here was an opportunity to put my newfound knowledge to use. Except that no one was teaching how to evaluate social programs in sociology graduate programs! I did have some experience with “program evaluation”. When I was directing a statewide child care project that was federally funded, some guy was hired by the state to evaluate my program. He met with me once at the beginning of the project, and at the end, he wrote a glowing report.

![]()

Every so often, I wondered if he’d be back. In the end, he really had no basis upon which to evaluate the strengths and challenges the project was facing – and believe me, there were plenty. But I wasn’t going to complain if he was phoning it in!

Since I had no idea how to evaluate a program, I hired someone who did, and for the next few years, she trained me and my sociologist friend, Claire, in how to use research skills to evaluate social programs. I never intended to continue doing this “applied” work for the next 20 years, but that is essentially what has happened. When I first started, I wasn’t very good at it, and I thought it was boring. But a couple decades later, I have learned a whole lot about how to do it well, and (luckily) find this work fascinating.

Making a choice to be an applied sociologist

The choice to be an “applied sociologist” is not a rejection or devaluation of academic sociology. It is a choice that is, in part, a function of economic imperatives – a tight job market, especially if you don’t want to move – but also a choice to make a different kind of difference. To impact the social world through organizations that are impacting people: through service, through organizing, and through education and advocacy, in the areas of public health, education, urban planning, climate change, arts and arts education and many more.

I have learned that it makes me happy to use the research and writing skills I learned in graduate school as a tool to help promote social change, through the vehicle of strengthening nonprofit organizations and improving philanthropic decision-making. Once considered the stepchild of the field, applied sociology is now gaining prominence, but largely because the economy has not produced the plethora of academic sociology jobs once predicted.

“Close to a perfect match”

In a 2013 article in Inside Higher Ed, Roberta Spalter-Roth, from the American Sociological Association, commented that “In sociology, there is close to a perfect match between available jobs and new Ph.D.s” (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/08/06/sociology-job-market-continues-recover-steadily). But this is only if you factor in the many government, nonprofit and research analyst jobs out there that require the skills and sociological perspectives learned in graduate school. Spalter-Roth notes that these jobs often pay more than university teaching positions, but graduates rarely know about them and professors may even discourage their students from entering these professions.

This year, my applied sociology friends and I agree that the “applied route” seems to be gaining some traction, with increased interest from universities and professional associations. A number of us have been on a (minor) speaking circuit, talking to graduate students at the request of sociology departments about choosing applied sociology as a career. And this year, the Sociology Department of a major research university, Boston College, hired me to teach a course on Evaluation Research. (Kudos to BC Sociology for recognizing the importance of this avenue for sociologists-in-training!)

Panel at Sociologists for Women in Society: Choosing Applied Sociology (sponsored by the Career Development Committee)

Given this increased interest, and what I believe is a need for sociologists to promote the health and well-being of organizations and communities using research and sociological principles, I organized a panel on this topic at an annual meeting of my favorite national feminist sociology organization, Sociologists for Women in Society.

The panel included three distinguished applied sociologists from the DC area, where the meeting was held, who presented about why they chose this route of practice, what they do and for what populations, and how they incorporate sociological principles into their work, framed by a race, class, gender lens.

The speakers, all based in DC, included Tekisha Everette, a lobbyist for the American Diabetes Association; Andrea Robles, a research analyst at the Corporation for National and Community Service; and Chantal Hailey, who ran evaluation projects at the national Urban Institute and elsewhere, and is currently a sociology doctoral student at NYU. One other panelist, Rita Stephens, was not able to make it because of a blasted snowstorm, but she would have rounded out the panel very nicely as she works at the State Department. The three women spoke to a standing and sitting room only crowd at the meeting, followed by numerous informal conversations, attesting to the fact that there is a hunger for this kind of work.

In my next couple of blog posts, I will allow these amazing women’s words speak for themselves. I hope that their words stimulate a dialogue about the value of and choice to pursue sociology outside of the academy. Based on the remarkable response at this meeting and in classrooms where I talk about applied sociology, my sense is that sociologists want to know about alternatives to working within academia. The words of these speakers inspired me and I hope they inspire you.

“I was interested in doing applied work that could lead to positive social

change. Somehow, it seemed like I wanted to be part of making the world

a better place.”

Sociologist, Andrea Robles

Corporation for National and Community Service

Check out this excellent blog post by Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, Research and Social Media Consultant with Social Science Insights in Australia, called What is Applied Sociology?, published in Sociology at Work: Working for Social Change: http://sociologyatwork.org/about/what-is-applied-sociology/

*Brandeis University, which is actually in the suburb of Waltham, Massachusetts, but looked like the country to this city girl!

by Mindy Fried | Feb 12, 2013 | conservatives, ethnicity, G.O.P., gender, health, health care, inequality, progressive policies, race, Republicans, social class, social policy, social science research

The American Enterprise Institute just published a speech by G.O.P. darling and House Majority Leader, Eric Cantor, in which he calls for cutting all federal funds for social science research, insisting that the money would be better spent finding cures to diseases. He uses the story of a child named Katie who battled cancer, and who “just happened” to be sitting in the front row of his audience. “Katie became a part of my congressional office’s family and even interned with us”, he is quoted as saying. “We rooted for her, and prayed for her. Today, she is a bright 12-year-old that is making her own life work despite ongoing challenges…Katie, thank you for being here with us”.

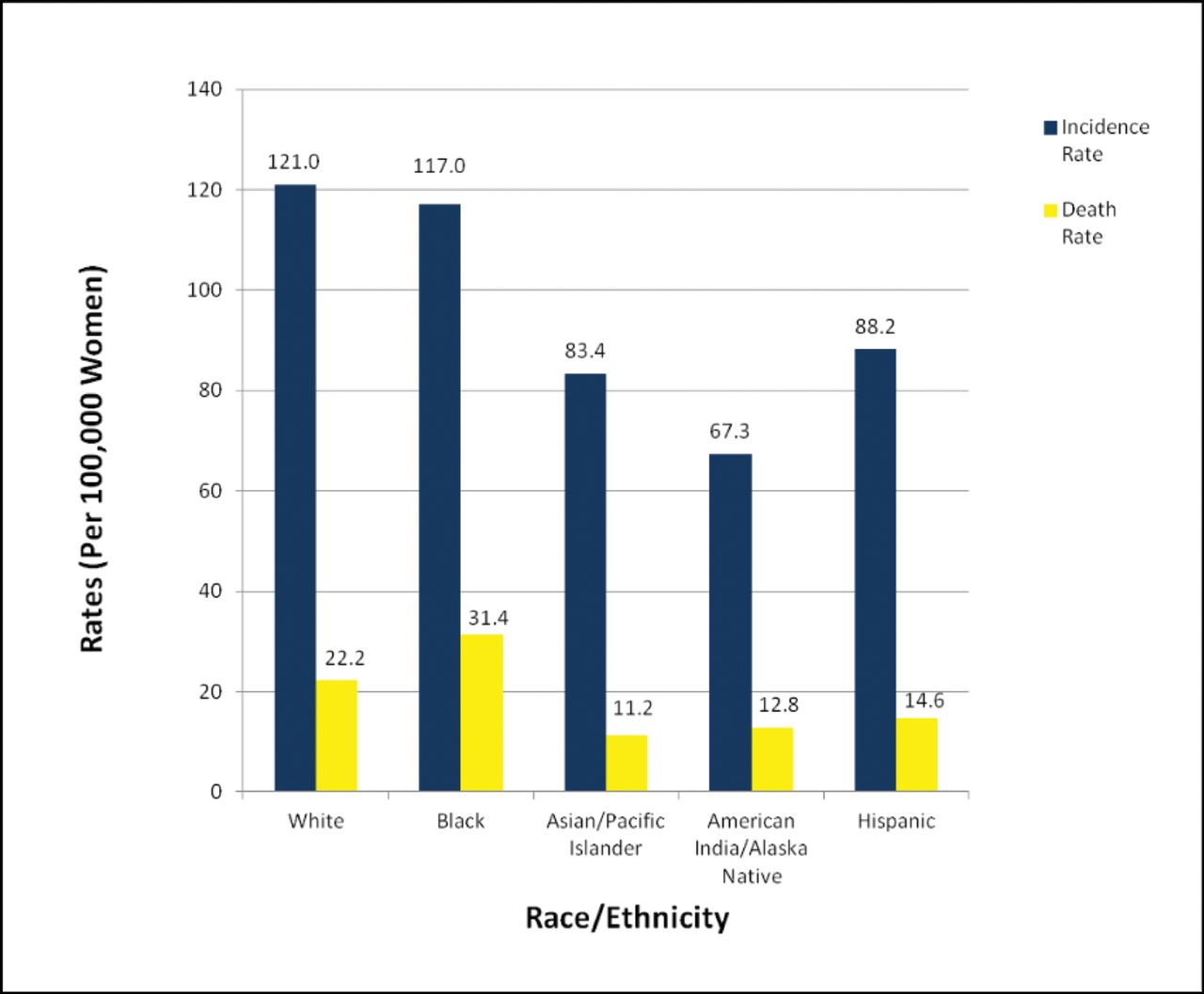

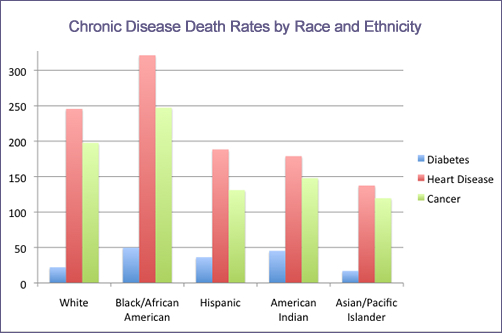

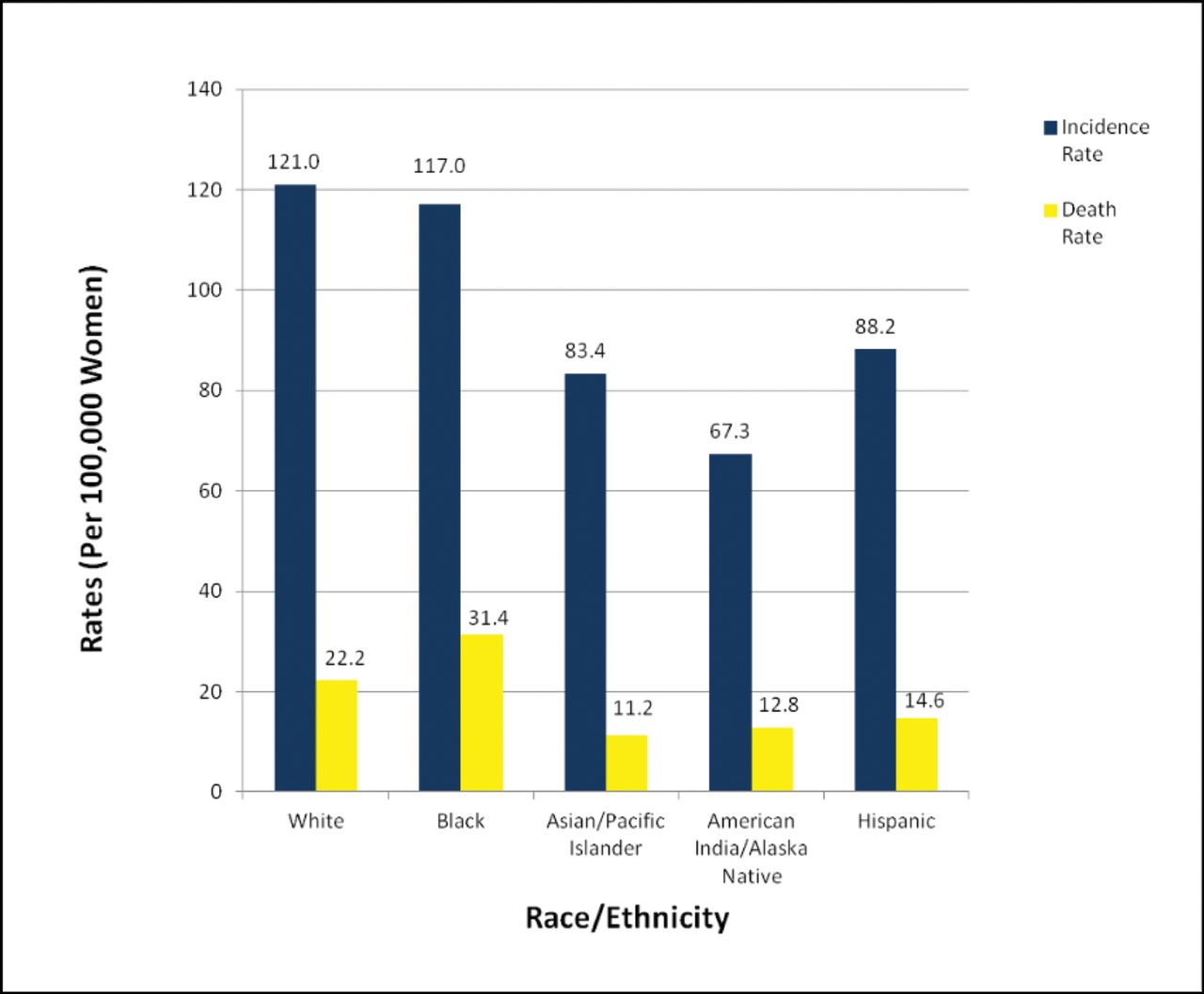

(Please note that the graphic visualizations in this post illustrate the importance of information generated through social science research which have critical implications for policy, e.g., the disproportionate impact of poverty on health outcomes by race/ethnicity) .

I can imagine the emotions in that room, as the audience learns that Katie’s disease is now in remission. Some people of faith in the crowd might be thinking that prayers led to the improvement in her health. But Cantor does not invoke divine intervention. Nor does he totally discount the role that publicly funded resources may have played in helping restore Katie’s health. On the contrary, he cannily declares that there is “an appropriate and necessary role for the federal government to ensure funding for basic medical research. Doing all we can to facilitate medical breakthroughs for people like Katie should be a priority. We can and must do better”.

But investing more public funds in research on medical cures, says Cantor, would require cuts in funding for social science research. Presumably, his argument is in the interests of budgetary discipline, because it makes no sense if the goal is to improve people’s health. Less social science research dollars will only weaken our capacity to understand the critical link between the social determinants of disease and health outcomes. We need to ask: Why did Katie get sick? Was she living near a power plant or did she go to a “sick school”? What kinds of services did she have access to? What is Katie’s ethnic/racial background? What is her class background? Because chances are, if Katie is white and middle-class, her access to services are better than if she’s black or Latino and poor.

Cantor trots out the familiar conservative template: We need policies that are based on “self-reliance, faith in the individual, trust in the family and accountability in government”. He declares that the House Majority – aka Republicans – “will pursue an agenda based on a shared vision of creating the conditions for health, happiness, and prosperity for more Americans and their families. And to restrain Washington from interfering in those pursuits”.

But while Cantor frames this as a message of empowerment, his solutions will only reproduce and expand poverty and inequality. Self-reliance is code for slashing government funding. Restraining Washington from interfering with health and prosperity will mean reducing taxes for the rich. And cutting social science research will eliminate needed publicly-funded analyses that provide an essential critique of social and economic policies and their impact.

Cantor’s stance is calculated to appeal to people who are struggling in a tough economy. In his speech, he argues that in America, where two bicycle mechanics, the Wright Brothers, “gave mankind the gift of flight”, we have the power to overcome adversity. “That’s who we are”, he says. Moreover, he argues that throughout history, “children were largely consigned to the same station in life as their parents. But not here. In America, the son of a shoe salesman can grow up to be president. In America, the daughter of a poor single mother can grow up to own her own television network. In America, the grandson of poor immigrants who fled religious persecution in Russia can become the majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives”.

All I can say is, sign me up, Eric! I’m the grand-daughter of a Russian immigrant, and maybe I’d like to become the majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives! Honestly? I get weary when I hear about the American dream from another rich, white guy who points to exceptions to the rule, and cynically tries to generalize them.

I just came back from a four-day feminist sociology meeting, sponsored by the organization, Sociologists for Women in Society (SWS) http://www.socwomen.org/web/, in which 250 scholars from around the U.S. and beyond, shared their research about how gender, race and class affect power and status, and how these determinants affect the realities of people’s lives – including their access to quality health care, decent jobs with benefits, high quality education, freedom from discrimination, and safe environments. These are the conditions that Cantor claims should be the right of all Americans, and yet his agenda makes them all less achievable. If Eric Cantor had been at that conference for just one hour, he would have heard about the importance of social science research in understanding systems that reproduce disadvantage for low-income people, immigrants, people of color, same-sex couples and more… But maybe if you preach self-reliance, limited government involvement, and the power of prayer, even a group of brilliant social scientists won’t change your mind.