by Mindy Fried | Jan 13, 2013 | arts education, arts education research, child development, dance education, early education and care, education, federal funding, music education, program evaluation, state budgets, youth theater

Over a year ago, I wrote a blog post about the importance of funding arts education. I’m still thinking about these issues, so here is Part Two: Save the arts because the arts save lives...

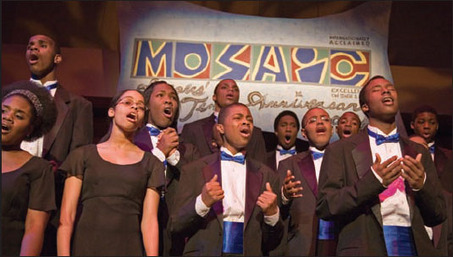

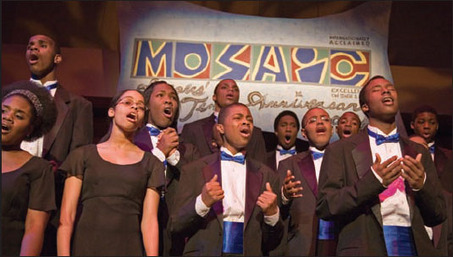

The arts – dance, theater, music, writing and the visual arts – have a powerful impact on children, opening the door to deeper knowledge and self-expression. I know from personal experience, and I have seen it in young people far and wide. While the current administration has said all the right things about arts education, this is sadly not enough, because federal, state and local policies STILL favor standardized testing and severely limit arts education funding. With all the concern about remaining competitive in a global market, this is precisely the time to fund arts education and allow our children to thrive.

I started taking dance lessons at age seven. For the first year, I did ballet, but only lasted one year because the teacher was nasty and the movements were too rigid for my soul. Instead my mother found a modern dance teacher, Seenie Rothier, a kind and ageless woman with a lean body and tight bun (and buns), who spoke with a raspy voice as she led her charges through endless contractions, swirls and triplets across the floor. Trained in Martha Graham-style dance, Seenie, as we all called her, had a penchant for the dramatic, and yet she was the most grounding element in my life. I always assumed that my family life was your average normal, and yet looking back, I have realized that it was a household rife with angry silence and disappointment. Seenie’s studio on Hertel Street in Buffalo, was just up the block from Kaufman’s Deli where they sold frosted brownies, and down the block from my grandparents’ working class neighborhood. It was my salvation. She recognized my talent, and by the time I was thirteen, had invited me to join a college dance troupe. Dance was my manna and still is.

While it is hard to “make a living” as an artist, I tried my best, working as a dance therapist in a psychiatric hospital and later, teaching dance as a resident artist in the Syracuse, New York public school system. I discovered the magic of movement as a source of expression for young children. Often in these schools, children were marched into the gym in single file, and told to remain quiet and respectful of the visiting teacher.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.

Dance is a healer, a universal mode of communication that is good for children. It’s natural. It’s great exercise. It wakes up the brain. It gives children an outlet. I have observed talented movement professionals use movement with children to help them learn science and math concepts. Dance can strengthen children’s emotional intelligence, and their ability to collaborate with others. And it can provide a form of discipline and order, when students are challenged to create dances that have beginnings, middles and ends.

A number of studies (see Critical Links) cite a positive correlation between dance experiences and nonverbal reasoning skills. One study demonstrated that “subjects” who were exposed to creative dance made significant gains in creative and critical thinking. And another study conducted with children with behavioral disorders found that when dance and poetry were combined, students’ were engaged and their social skills improved. Another study that promoted reading through dance to elementary children found that students improved significantly on all measures assessed by a reading test, including their ability to relate written consonants and vowels to their sounds.

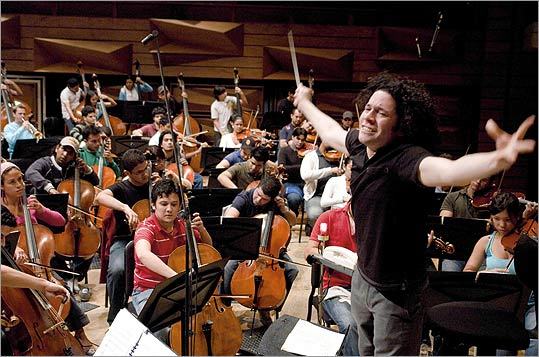

The research on other arts modalities is equally strong, linking the study of theater to literacy, music education to improvements in spatial-temporal reasoning, achievement in reading, and reinforcement of social-emotional and behavioral skills. And classrooms that integrate the arts are a leveler for all students, including those with disabilities.

In my own research, I’ve found that teachers who implemented arts-integrated curriculum into their classroom had increased enthusiasm for teaching as they observed the positive response from students, both in terms of their attitudes towards learning, but also their ability to learn.

It’s time to broaden the policy dialogue and demand increased funding for arts education!

by Mindy Fried | Jul 3, 2010 | child care, early education and care, policy, poverty, state budgets, value of caregiving work, women and work

In the early 1980s, I was radicalized by a small band of smart and committed child care workers who lobbied me when I was working for Jack Backman, a progressive state Senator in Massachusetts. First of all, as a new Bostonian who was just starting on the job, I was totally flattered that anyone would lobby me! But moreover, these incredible child care teachers were activists who loved children and understood firsthand the wage inequities for teachers caring for young children. The governor at the time called child care a “Cadillac service”, in other words, something superfluous – because women were expected to be primary caregivers for their children. But even then, 30 years ago, this view was way out of sync with the reality of women in the labor force, and especially the rise of mothers – about ½ of all mothers with infants and around ¾ of mothers with children under 5 – who continued to work for pay after their babies were born.

My child care activist buddies did their work well, and I came to believe that childcare– or early care and education as it is now called – was one of the most important issues for working parents and their children. It wasn’t a hard sell for Senator Backman, who sponsored a bill to create universal child care for all. At the time, this bill seemed outrageous, the kind of outrageous that inspired behind-his-back twitters (the old-fashioned, non-techy kind). But I have learned that in the world of policy, we NEED outrageous to push the debate towards the possible…

Suffice it to say, the bill never went anywhere. Over these past 30 years, the child care movement has matured into the early childhood education movement, fueled in part by the push for educational achievement of young children, as well as by the economic reality that two-parent families need/require stable child care services to maintain economic stability. The movement throughout the country around early care and education continues to grow. There has been progress, and Massachusetts has had some notable victories. A few decades after Senator Backman’s failed legislation, a Massachusetts-based group called the Early Education for All Campaign, mobilized support among legislators and advocates around a universal pre-kindergarten bill. The bill passed, creating access to public education for all Massachusetts 4-year-olds.

But there’s still a long way to go, and we could learn a lot from family policies in Europe that include paid parental leave, universal child care (that serves very young children), and non-stigmatized financial support for family caregiving…

Short of more radical change, we need to unravel some of the systemic glitches…

In a recent NY Times article (5/23: Cuts to Child Care Subsidy Thwarts More Job Seekers) – we learn that the Arizona state budget has cut funding for subsidized child care, forcing some low-income mothers to quit their jobs and instead receive state welfare benefits. These are single women who depend on their salaries to support their families. They will look for another job, but they need to keep their salaries below a certain limit to access subsidized child care.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/24/business/economy/24childcare.html?pagewanted=3&sq=child%20care%20subsidy%20thwarts&st=cse&scp=1),

What’s wrong with this picture? Once again – or should I say still – we see that early care and education services are critical to family survival, and our social welfare policies in this nation undermine family economic stability.

by Mindy Fried | May 25, 2010 | child care, policy, state budgets, women and work

In the early 1980s, I was radicalized by a small band of smart and committed child care workers who lobbied me when I was working for Jack Backman, a progressive state Senator in Massachusetts. First of all, as a new Bostonian who was just starting on the job, I was totally flattered that anyone would lobby me! But moreover, these incredible child care teachers were activists who loved children and understood firsthand the wage inequities for teachers caring for young children. The governor at the time called child care a “Cadillac service”, in other words, something superfluous – because women were expected to be primary caregivers for their children. But even then, 30 years ago, this view was way out of sync with the reality of women in the labor force, and especially the rise of mothers – about ½ of all mothers with infants and around ¾ of mothers with children under 5 – who continued to work for pay after their babies were born.

My child care activist buddies did their work well, and I came to believe that childcare– or early care and education as it is now called – was one of the most important issues for working parents and their children. It wasn’t a hard sell for Senator Backman, who sponsored a bill to create universal child care for all. At the time, this bill seemed outrageous, the kind of outrageous that inspired behind-his-back twitters (the old-fashioned, non-techy kind). But I have learned that in the world of policy, we NEED outrageous to push the debate towards the possible…

Suffice it to say, the bill never went anywhere. Over these past 30 years, the child care movement has matured into the early childhood education movement, fueled in part by the push for educational achievement of young children, as well as by the economic reality that two-parent families need/require stable child care services to maintain economic stability. The movement throughout the country around early care and education continues to grow. There has been progress, and Massachusetts has had some notable victories. A few decades after Senator Backman’s failed legislation, a Massachusetts-based group called the Early Education for All Campaign, mobilized support among legislators and advocates around a universal pre-kindergarten bill. The bill passed, creating access to public education for all Massachusetts 4-year-olds.

But there’s still a long way to go, and we could learn a lot from family policies in Europe that include paid parental leave, universal child care (that serves very young children), and non-stigmatized financial support for family caregiving…

Short of more radical change, we need to unravel some of the systemic glitches…

In a recent NY Times article (5/23: Cuts to Child Care Subsidy Thwarts More Job Seekers) – we learn that the Arizona state budget has cut funding for subsidized child care, forcing some low-income mothers to quit their jobs and instead receive state welfare benefits. These are single women who depend on their salaries to support their families. They will look for another job, but they need to keep their salaries below a certain limit to access subsidized child care.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/24/business/economy/24childcare.html?pagewanted=3&sq=child%20care%20subsidy%20thwarts&st=cse&scp=1),

What’s wrong with this picture? Once again – or should I say still – we see that early care and education services are critical to family survival, and our social welfare policies in this nation undermine family economic stability.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.