by Mindy Fried | Mar 12, 2013 | arts, arts education, AWP conference, creative writing, loss, sociological imagination, women and work, women artists

Writing is a solo act, but for those in attendance at the conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, or AWP (https://www.awpwriter.org/) this past weekend, you’d think it was one big party, with over 12,000 people moving through the sterile hallways of Boston’s massive Hynes Convention Center to attend hundreds of sessions. I had been forewarned that this event was downright overwhelming. So before I stepped foot into the Hynes, I carefully studied the program, selected sessions that fit my criteria, and found out exactly where they were physically located. Getting lost in the Convention Center was not on my agenda! As it turned out, this surgical approach served me well.

In one day, I managed to attend five sessions, chat with five random strangers, purchase an energy bar for nearly $5, and wander around the book fair where I was invited by at least five non-residency writing programs to look at their literature. I spoke with five or so small presses about their books, and was also accosted by a woman selling a weeklong “writing trip” to Paris, which was, in sum, a total rip-off. Of my small sample of informal interviewees, a few were undergraduate creative writing majors who were totally blown away by the panoply of rich resources in one place; one was an art history professor and another was a writing professor.

But I wasn’t there to make friends, although later I joined the Women’s Caucus of the organization (yes, there is gender bias everywhere!). I was there because I’m writing a memoir about the experience of caring for my dad in his final year of life, in which I am inter-weaving my family’s experience of political persecution, the FBI and more. I wanted to hear published authors talk about their experience writing memoirs, and to garner some tips about the process of publishing this type of book.

Here are a few gems that I got from the conference:

In a panel called “The Art of Losing”, authors talked about how profound personal loss fuels their writing. One of my favorite speakers on this panel was Jennine Capó Cruce, author of How to Leave Hialeah (http://www.jcapocrucet.com/), who said that she was told that she shouldn’t write from anger. But as she wrote her book, she saw rage as her source, and while writing her book, recognized that underneath her rage was grief.

In a panel called “How Do You Know You’re Ready?”, novelists shared stories about manuscripts they either sent to agents too soon or had locked in drawers, never to see the light of day. I realized that the question of when a book is complete is a universal question. The panelists seemed to agree that knowing when you’re done writing a book is a “visceral thing”. I was touched that the panelists also welcomed attendees to approach them with questions at the end of the session. I asked novelist Dawn Tripp (http://www.dawntripp.com/) for suggestions about making a “pitch” to an agent. She offered me a few tips, including “make it short and to the point”. And another panelist, Kim Wright, author of Love in Mid-Air (http://loveinmidair.com/), added that it’s important to maintain the voice of the book when you’re trying to get others interested.

In a session called “Memoir Beyond the Self”, panelists talked about the importance of writing from one’s personal experience and broadening it to reflect on cultural implications. Travel writer and journalist, Colleen Kinder (http://www.colleenkinder.com/Colleenkinder/home.html) said, “personal essays have to be brave”, and she talked about the importance of “braiding” and “weaving” different strands of a story together. In describing this braiding and weaving process, Leslie Jamison, author of Empathy Exams (http://www.graywolfpress.org/Latest_News/Latest_News/Leslie_Jamison_wins_Graywolf_Press_Nonfiction_Prize//) said that “something in one sphere poses a question that another sphere can answer”. That intrigued me.

In a session called, “It’s Complicated: Memoir-Writing in the Political Sphere”, Melissa Febos talked about her book, Whip Smart, in which she wrote about her three years as a dominatrix while attending a liberal arts college in New York City (http://melissafebos.com/). Kassi Underwood talked about her book, A Lost Child, but Not Mine (http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/fashion/a-lost-child-but-not-mine-modern-love.html?pagewanted=all), which chronicles her experience of having an abortion and then encountering her ex-boyfriend who was now a father. And Nick Flynn described the writing of his book, Another Night in Suck City about seeing his estranged father in the homeless shelter where he worked. The book was later turned into a film called, “Being Flynn” with Robert DeNiro and Julianne Moore. Talk about star struck!

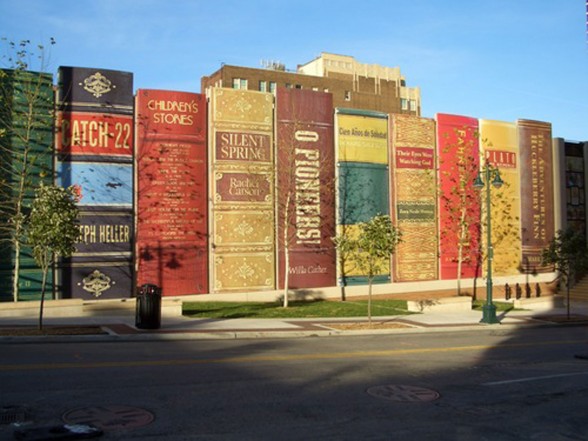

In a session called “Poetics of Fiction in/at Buffalo”, three writers read from their work about my poverty-stricken, yet vibrant hometown of Buffalo, New York. Ted Pelton (http://www.starcherone.com/ted/) began with this poem: “Buffalo Buffalo, Buffalo Buffalo Buffalo…”, saying that no other city can be a noun, verb and adjective. And Buffalo writer of Buffalo Noir, Dmitri Anastasopoulos (http://www.akashicbooks.com/catalog-tag/dimitri-anastasopoulos/), brought the experience full circle for me, when he said, “Buffalo is all about loss”.

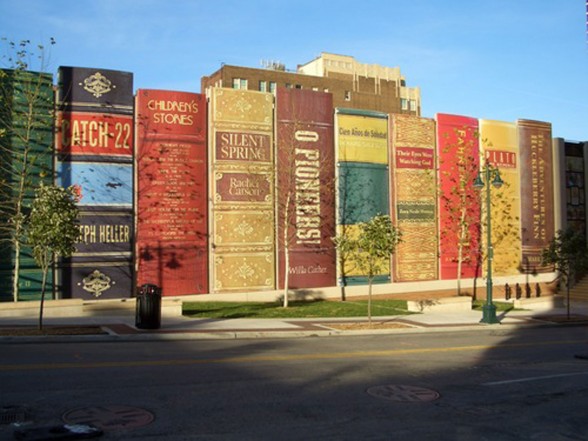

The conference had a commercial element as well: In a so-called “Book Fair”, the small presses are there to entice writers, as are the creative writing programs and artists’ retreats. But one of my favorite booths in the exhibition hall was run by 826 National, a nonprofit organization that runs eight writing and tutoring centers around the country, aimed at helping at-risk youth find a voice to tell their stories (http://www.826national.org/). And who knows? Perhaps these young people will be the authors of tomorrow, and future attendees of this chaotic but enriching experience that is AWP…

by Mindy Fried | Sep 30, 2010 | child care, depression, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, women artists

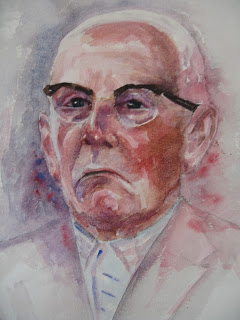

This is a picture of me and my mother. You’d never know from looking at the expression on her face that she hated being a “homemaker”. In fact, she looked pretty happy hanging out with me, even if we were washing dishes! In her younger years, prior to the birth of her two daughters, she wrote sultry torch songs and had her own radio show. Later, she studied painting and then continued to paint portraits until her final days. When I was a teenager, she exhibited her paintings every year in an outdoor art festival, near a studio she rented in what was considered the bohemian part of Buffalo, New York, my home town. Despite being an adolescent, this was the one and only weekend – every year – that I thought my mother was really cool.

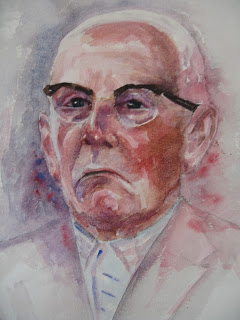

Here is one of her watercolors that I still really love. Middle-class women of my mother’s generation – caught between the suffragettes of the early twentieth century and the second wave of the women’s movement of the 1970s – did not have an organized “sisterhood” of women supporting them to step out of the kitchen. As an artist, my mother was passionate about her work, but it was never considered a career, nor did it generate much income, even though she taught painting and sold commissioned portraits. In fact, in her era of young motherhood – the 40s and 50s – single middle-class women who worked for pay were expected to leave their jobs once they were married. As we know now, the independence of women is often tied to their earning capacity, and not being considered a professional was hard on her. This phenomenon was eventually coined the “problem without a name” by Betty Friedan.

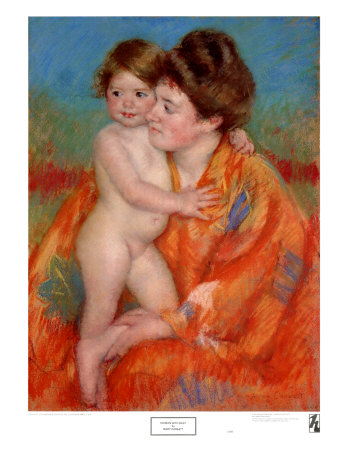

My mother’s favorite artist, Mary Cassatt, is quoted as saying:

“There’s only one thing in life for a woman; it’s to be a mother…A woman artist must be…capable of making primary sacrifices.”

How ironic, given that Cassatt never married, nor did she have children; and for many years she painted portraits of mothers and children!

Reflecting the schizophrenic existence of a strong-willed woman of that era, Cassatt also said,

“I am independent! I can live alone and I love to work!”

Even though her family objected to her becoming a professional artist, Cassatt began studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia – where my mother also studied art for one year. I never spoke to my mother about why she left, but Cassatt also left after one year, complaining that “there was no teaching” at the Academy. Unlike male students, females couldn’t use live models. This is likely just one of the inequities she encountered there. When she left, Cassatt moved to Paris. When my mother left, she moved back to Buffalo, New York…

My mother’s life was one of sacrifices, like so many women of her generation. The arts were a place for talented and creative women for whom other professional careers were closed. Maybe it was a vestige of the Victorian era when it was considered proper for upper-class girls and women to “dabble” in the arts. To be considered a serious artist was another thing though. And my mother always struggled to be considered a professional. It irked her when the realists or even the abstract expressionists – always male – won the competitions she entered. She intuitively understood that there was gender bias, but the proof was invisible. To be an artist means expressing oneself – putting one’s vision into the universe to challenge and inspire or simply to portray beauty. In an era where women’s voices were not heard, being a woman artist was revolutionary.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

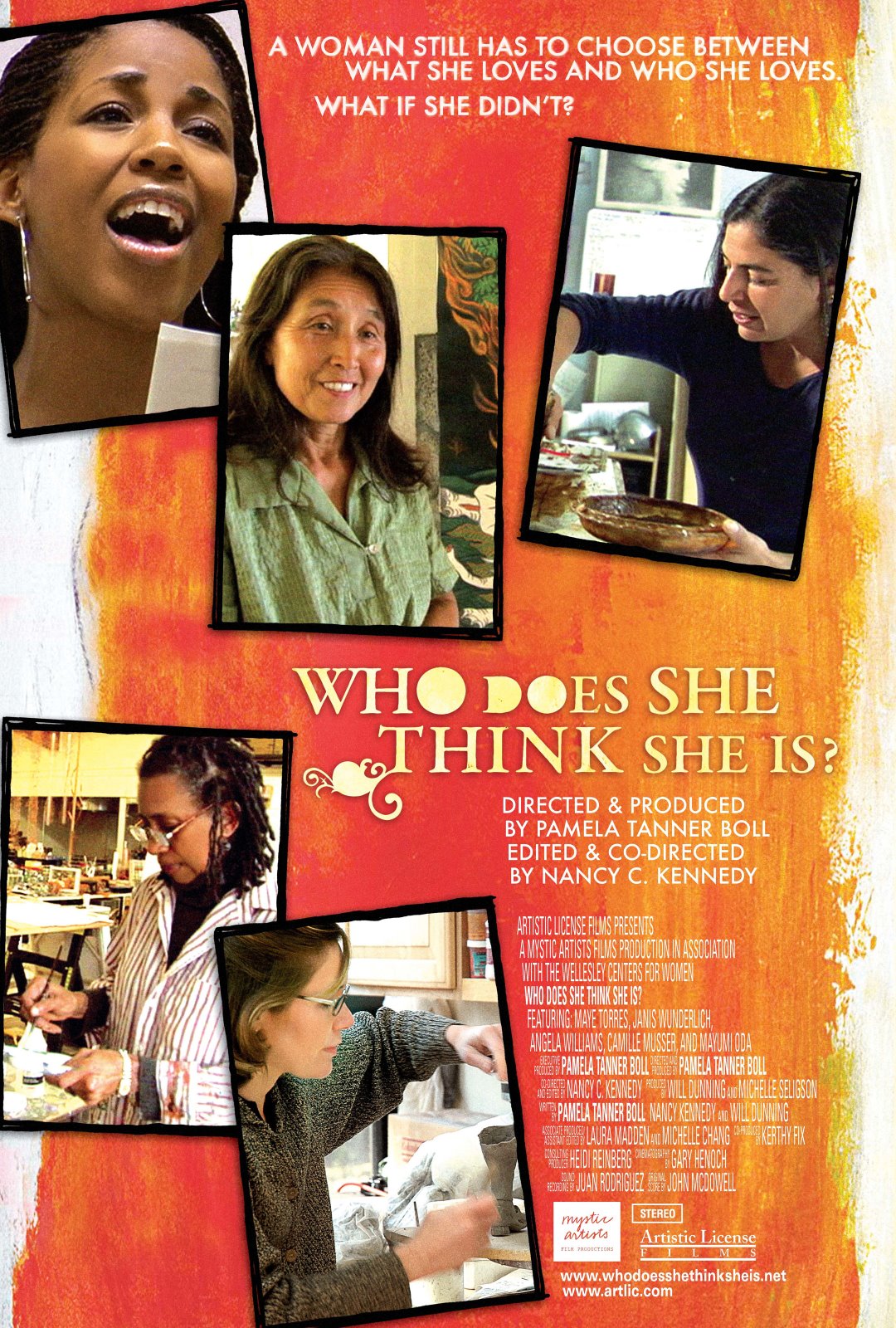

In a film about women artists called “Who does she think she is? – produced by Pamela Tanner Boll (who also produced Born into Brothels) – artists reflect on the challenges they face balancing their work and family demands.

They talk about how they’re not taken seriously precisely because they’re women. In fact, while 80% of students in visual arts schools are women, “in the real world,” 70-80% of artists whose works are shown in galleries and museums are male.

In an article in the New York Times, Marci Alboher says these statistics “sound alarmingly like the numbers released by organizations that track the presence of women in the highest echelons of professions like law, journalism, engineering or finance.” The women artists in the film also argue that they are dissuaded from focusing their art on the subject of mothers and children, because it is not considered “real” material. Both artist and subject are devalued…

Outside the art world, says Alboher, people rarely discuss the challenges faced by women artists “moving up the ranks.” This has a lot to do with the fact that women are still considered primary caregivers in this society. Despite the large percentage of mothers in the labor force, we are still defined primarily by our capacity to bear children. Most workplaces do not accommodate the need for work-life balance for their employees, be they women or men.

As a teenager, I was often frustrated by my mother’s lack of confidence in her work. I wanted her to be a strong role model in many ways, someone who followed her passion and knew she had talent as an artist. But now I have an increased understanding of the effects of working in isolation, in a society that didn’t value the work of women artists, and in the microcosm of that society, in a family that expected her to have dinner on the table every night. (No wonder she hated to cook!)

I love the comment by Georgia O’Keefe who once said,

“I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking the time to look at it. I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

It takes guts to think that your painting will stop New Yorkers in their tracks! But while guts are good, women’s voices need to be valued; the balance of caregiving must be shared; workplaces need to accommodate the work-life balance needs of parents; and social policy must broaden to include paid parental leave and universal, free early care and education.

According to a 2008 National Endowment for the Arts report called “Artists in the Workforce: 1990-2005”, women artists are as likely to marry as women workers in general, but… they are less likely to have children! Only 29% of women artists had children under 18, almost six percentage points lower than for women workers in general. So like Cassatt, it appears that many contemporary women artists have decided to avoid the social institution of motherhood.

The incredible Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo, once said, “Painting completed my life.” I think my mother felt the same way, even though she never achieved traditional “success” as a painter…