by Mindy Fried | Dec 8, 2010 | productivity, women and work, work and family balance, work statistics

I just wrote the following piece for WorkplaceFlexibility.com.au, based in Australia. Thanks to Juliet Bourke from Aequus Partners for allowing reproduction:

After considerable debate, the U.S. Congress has finally approved the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010.

The Bill, which has passed both the House and the Senate, is now awaiting President Obama’s signature. Once that happens, federal agencies will be required to develop a policy that allows eligible employees to do at least some portion of their work outside of the office, with the aid of electronic communications. Agencies will also be required to incorporate this alternative arrangement into its operational planning for natural and other disasters.

Why it’s a no-brainer…

There is an abundance of research data demonstrating the positive effects of teleworking – or telecommuting – on employee well-being and on the employer’s bottom line. In a “meta-analysis” of 46 studies of telecommuting involving 12,833 employees, Pennsylvania State University psychologists, Ravi Gajendran and David A. Harrison, found that telecommuting was a win-win for both employees and employers.

Telecommuting gives employees a sense of freedom at work, which contributes to job satisfaction. It reduces stress and helps workers balance their work and personal responsibilities. Employees who telecommute maintain and increase their productivity. Having access to telecommuting increases workers’ loyalty; and working outside of the office for one or two days per week has no negative effect on employee relations with coworkers or managers.

Gejendran and Harrison’s findings reflect what I learned in a small qualitative study of women telecommuters who were employed in several major American corporations. Despite the dramatic influx of women into the paid labor force in the past few decades, they continue to be the primary caregivers within their families. With inadequate government family policies in the U.S., and the limited response within the private sector to employees’ family concerns, our society is experiencing an enormous care gap. Telecommuting provides women – and increasingly men – with a legitimate avenue to combine and/or accommodate their market work and caregiving responsibilities.

The women telecommuters I interviewed claimed that the arrangement improved their work-life balance, allowing them to have more control over when and where they performed their work. At the same time, telecommuting helped them to maximize their productivity, serving the ultimate objective of employers. One telecommuter I interviewed for the study told me that she was able to maintain her work, despite dealing with a serious health problem.

“I’ve just been diagnosed with breast cancer, so about a month ago I had surgery and now I’m getting radiation every day, and in the summer I will start chemotherapy. So being a telecommuter is enabling me to work from home if I’m not well enough to come into the office.”

And a manager of a customer service department told me that telecommuting, while supporting employees’ needs, also benefited the company’s bottom line. Describing his rationale for implementing a telecommuting policy in his department, he said,

“People can do the same thing they can do in the office at home and save them the wear and tear of coming to work, the wear and tear of a long commute in many instances, maybe tolls… schlepping around with the kids trying to go to a child development center. The company benefits to the extent that every time we have a bad weather close-down, we have people on the phone at home instead of disruption of service. So it’s a win-win on both sides.”

Trial run in the States…

Indeed, telecommuting has been instituted in a number of U.S. federal agencies already, as well as in numerous corporations. In a 2004 study of 74 federal agencies, 43% of employees (323,292) reported that they were eligible to telework, compared to 35% of employees (625,313) in 2002, representing a gain of more than 20%. And in the overall U.S. labor force – including public and private employers – it’s estimated that more than 33.7 million workers telework at least one day per month.

Moreover, 22 states have already passed telework legislation. A number have implemented these policies to address environmental concerns or traffic congestion; some states encourage private employers to implement telecommuting programs; and others have statutes connecting employee productivity and efficiency to telecommuting, or promoting “a better quality of life.”

Historically, many federal policies in the U.S. are first implemented at the state level. This was the case for Social Security, health care reform, maternity and parental leave, and even civil rights legislation. The federal legislation was the culmination of pressure in smaller policy environments. But having a federal bill can also provide a model for more universal implementation. In addition to creating a mandate for federal agencies, hopefully the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 will provide encouragement for additional states and private sector employers to institute or expand their telecommuting policies.

Making the Bill real…

While the effects of telecommuting are positive for employers and employees, it is only workable for certain types of work and with certain employees, and therefore not a universal solution to problems in workplace policy. But it is particularly well-suited for those doing “knowledge work” that can be effectively performed in multiple locations with the help of electronic communications.

Even for those who have jobs that are conducive to telecommuting, the face-time culture of most organizations may undercut its utilization. It’s one thing to have a policy, and yet another to have employees use it. The Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 requires training for employers and employees, which is a critical element to shift an organization’s culture.

In my telecommuting study, I found that even those who felt supported for their work at home felt it was a privilege, and in turn, worked additional hours to “prove” their loyalty. But when they did use a policy, it improved their quality of life.

The cost/benefit debate…

The sad fact is that Republican opposition to the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 is not based on what’s good for employees or employers. It simply affords Republicans another opportunity to say that less government is better. But that argument doesn’t make sense if the policy is administered with care. Representative Virginia Foxx, a Republican legislator from North Carolina, argued that with a high unemployment rate, it is a “travesty” that Democrats are “pushing this initiative to make it easier for federal employees – who already have it much easier than the rest of the country – to avoid the office.”

Rep. Darrell Issa, a Republican legislator from California, said that the law adds a layer of bureaucracy into federal agencies, claiming that Americans want less government. Bolstered by recent elections of conservative Republicans to Congress, he says, “This will be the first vote after the American people said no to government waste, fraud and abuse, government growth and government spending.” Issa will undoubtedly try to amend or change this legislation when he begins his role as the new Chair of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. According to the New York Times, Issa’s plans are part of a larger Republican agenda to vastly expand scrutiny of the Obama administration and aggressively push to cut spending and shrink the government, focusing on “excesses and waste.”

Democrats who supported the passage of the telework legislation provided evidence regarding its cost-effectiveness. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that implementing the bill will cost around $30 million over five years, but the return on this investment will pay off over time. Representative Stephen Lynch, a Democratic legislator from Massachusetts and my very own Congressional representative, said the long-term savings will provide an “excellent return” on this initial investment. And indeed, the experience of many private companies suggest that he’s right on the money. IBM has saved as much as $56 million annually and reduced office space by allowing employees to telework; Cisco generated an estimated annual savings of $277 million in productivity by allowing employees to telecommute. And IBM Canada currently saves $20 million in operating costs annually and over 500,000 feet of real estate with its telework program.

Let’s hope that sanity – backed up by plenty of data and experience throughout the U.S. – will prevail once this sensible piece of legislation is signed by the President, and that the resistance will be met with reason.

by Mindy Fried | Nov 21, 2010 | child care, early education and care, family, parental leave policy, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, work statistics

Yesterday, I shared a long plane ride with a Japanese woman who was coming to the States to visit a friend. She patiently helped me try to track down an old Japanese friend via Google. Yes, there was WiFi on board; yes, Google in Japanese is very cool; and no, we were not successful in tracking her down! But more importantly, we talked about work and family issues, as she described the gendered division of labor in Japan. She is employed as a translator, but took a 10 year hiatus from her paid work – actually quit her job – to care for her son. This is typical, she said, among women “in her generation.” (After our conversation I calculated her age as around 43.)

In his book, The New Paradox for Japanese Women: Greater Choice, Greater inequality, Japanese economist Toshiaki Tachibanaki presents a gendered analysis of the Japanese economy. He reports that while Japanese women now have more choices in their careers than in earlier days when their education consisted of preparing them to be “good wives,” they now face job discrimination, sexual harassment and wage inequalities on the job. My new Japanese airplane friend commented that her husband wanted her to stay home with her son, telling her that it was the most important thing she could do. He, on the other hand, was working 12+ hour days. When I asked her if he was “able to” spend time “at home,” she winced and said that he did play with their son sometimes, but didn’t do any housework or cooking.

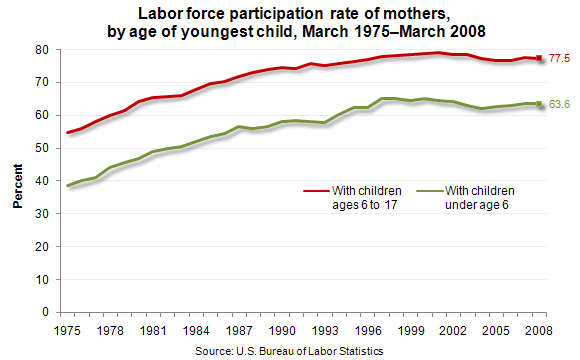

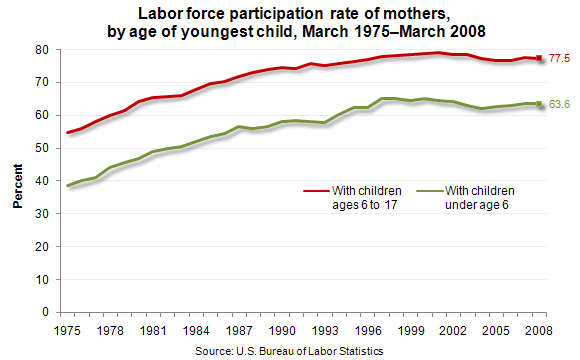

She was surprised to hear that over 75% of American mothers of school-age children work for pay. In Japan, nearly half of all women work in the labor force, but Japanese women earn less than half of what men earn. So it’s no surprise that women take on the brunt of the caregiving responsibilities, simply from an economic perspective. By the way, the gender wage gap in the US also is a significant problem, particularly for mothers, albeit less stark than in Japan.

She also described the dissolution of the extended family in which multiple generations lived together. Without a grandparent to do childcare, women in Japan have a harder time sustaining full time employment.

While we didn’t dive into a discussion of childcare policy in Japan, her observation got me thinking about the meaning of community and the gendered division of labor during my childhood years in the 50s. The 1950s in the U.S. are portrayed much like my Japanese friend’s description of contemporary Japanese culture, with the general assumption that mothers’ most important work was to stay at home with their children.

But what did staying at home actually mean in 1950s America? I know from personal experience, as a child of the 50s, I spent hours playing on the street with my friends. Whether it was kickball, dodgeball, relay or two-person races, or making up plays, we kept each other busy (on the street, as opposed to off the streets!). When I wasn’t in school or hanging out with my buddies on the street, I was taking dance classes or piano lessons. And when I wasn’t in school, on the street or at a lesson, I was firmly planted in front of our black-and-white TV, watching “traditional family life” in shows like Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best, and Ozzie and Harriet. While my mother was a “stay-at-home” mom, like the majority of middle-class mothers in that era, she and I didn’t spend a whole lot of time together because, frankly, I had other fish to fry!

Despite the glorification of family life in 1950s America, believe it or not, mothers today spend about the SAME amount of time as the 50s and 60s moms who did not work outside of the home! Family sociologist Suzanne Bianchi found that while the number of children with mothers in the paid labor force has gone up considerably between 1965 and 2000, there has actually been a slight INCREASE in the amount of time moms are spending with their children over these years now – from 10.6 hours per week in 1965 to 12.9 hours per week in 2000. Contemporary dads also spend a little more time with their kids these days, from 2.6 hours per week in 1965 to 6.5 hours per week in 2000.

So what’s the deal? Well it looks like a number of factors have converged to create this new reality, even though mothers and fathers spend a lot of time at their paid jobs. First of all, the work of the “at-home” mother has been greatly altered by technology and fast food. Meal preparation – especially when it comes from a takeout joint, comes out of a package, or pops out of the microwave oven – takes less time. Mothers are also spending less time cleaning the house, compared to a few decades ago. Dust bunnies prevail! And actually, fathers never spent a whole lot of time cleaning the house anyway, so no big change there.

But equally important, the notion of good parenting has shifted over the years from more hands-off to more intensive, involved parenting. From playing classical music to your in-utero fetus to knowing all your kids’ teachers to coaching her Little League team to texting daily with college age kids, the contemporary notion of “good parenting” has been redefined as engaged parenting. Based on the research, it seems that mothers who work outside the home want to “protect” the amount of time they have with their children; ergo, spend as much time with them as possible.

In her study of nurses who work night shifts, Anita Garey found these women chose night hours so they could maintain the notion of the “ideal mother” who was available to meet during the day with her child’s teachers, bake for the bake sales, and show up at school events. All this came at a cost: sleep and personal care. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild called this phenomenon the “time famine.” Bianchi argues that the increase of mothers in the paid labor force, at least in two-parent families, has shifted some of the caregiving responsibility to fathers, commenting,

“Perhaps most controversial, women’s reallocation of their time probably has changed men. The increase in women’s market work has facilitated the increase in women’s involvement in child-rearing, at least within marriage.”

Clearly, the economy is the driver in the U.S. and other parts of the world, creating an imperative for women to participate in the paid labor force. But women, like men, derive meaning from paid work, and the women’s movement of the 1970s – while rarely mentioned these days – had a powerful impact on women’s sense of entitlement in the workforce.

While we are not battling the level of tradition that exists within Japanese culture, we have a long way to go to achieve equity, particularly for mothers in the paid labor force.

To achieve real equity in the labor force, we need concrete changes in government policies that promote and protect wage equity for women, and protect against gender- and parent-based job discrimination. We need a paid parental leave policy, and support for shorter work hours so that parents of young children can choose to gradually return to full employment after taking a parental leave from the jobs. We need universal child care so that all young children have access to high-quality early education and care, and not just those in families that can afford it. And we need universal health care, so that workers are not reliant on a job for their health insurance. That’s too dangerous in this economic climate, and even with employer-based insurance, there is too much variability in the type of care provided.

Tall order? Maybe, but we need a comprehensive set of solutions to achieve “good parenting” in this age of work-family imbalance.

by Mindy Fried | Jul 3, 2010 | depression, finding work, unemployment, women and work, work statistics

Every so often, someone – generally some man – will ask me if I work, or even better, if I still work. In the past, this comment meant: Are you a “stay-at-home mom” (first reference), ergo, not doing “more important” work in the paid labor force; or are you retired because you’re old or don’t “need” to work (second reference)? Jeez! Most women – including those with kids – work for pay. And I’d like to think that I’m still “in my prime” in terms of my labor market participation. The truth is that, like so many Americans, I work like a maniac. Why? Because I have to; I derive pleasure and purpose from it; and hopefully I can contribute something meaningful to the world… But there’s a new interpretation to that question about whether I – or any of us – work, and it has to do with the increasing normalcy of unemployment.

Despite all the government’s attempts at jump-starting the economy, the rate of unemployment has remained stubbornly high at around 10%. A recent rise in the job rate was more related to the creation of temporary jobs. In fact, some of my friends who got hired as census workers were part of that faux decrease in the unemployment rate, and when their jobs end, the unemployment rate will likely go up. Unemployment affects people from all walks of life, but it disproportionately affects people of color. For example, the unemployment rate for white men is 8%, compared to a whopping 17.1% for African-American men and 11.1% for Latino men. The unemployment rate for white women is 7.4% versus 12.4% for African-American women and 10.3% for Latinas.

In this current recession, men initially experienced higher job losses than women, because the industries first hit – like housing, construction and manufacturing – are dominated by men. But downsizing has become an increasingly gender-neutral phenomenon. As the recession has expanded, women are losing more jobs and at a slightly faster rate than men in key sectors like retail and service work. According to Valerie Norton, a Public Policy Fellow at the National Women’s Law Center, in January, 2009, women’s unemployment was at the highest rate in 16 years and had the largest single-year increase in 33 years.

In the past few weeks, I have had numerous conversations with friends and acquaintances about the difficulty they’re having finding a job, or how they’re worried about being laid off from their current job. There’s the 20-something armed with degrees who has been thinking about launching a business and meanwhile is working in unpaid internships. There’s the highly educated manager who thought her job was stable, but her organization doesn’t have the funds to cover her, so she’s scrambling to network with contacts near and far. And there’s that person I knew ten years ago and haven’t heard from in ages who suddenly asked me to “link in”. I don’t blame her; I’d be doing the same thing.

I empathize with each of their circumstances. I’ve been out-of-a-job or underemployed a few times in my life, and because I make my living as a consultant, it could happen again. The first time I was without a job, I was in my early 20s. I had worked for a year in a psychiatric hospital and saved enough money to travel in Europe for nearly a year. I came back home – job-less – to an icy, grey Syracuse, New York winter, with no prospects or plans. Poor me… (you think). I had the time of my life, being carefree, so it’s probably hard to “feel my pain.” But I discovered a very dark place emotionally that lingered for months. Although I only had me to support, I was still terrified of the abyss that seemed to lie in my future. Ultimately, I ended up in graduate school, that legitimating haven for the unemployed (that is, those who can afford it time-wise and financially). With a nice scholarship, I had returned to the familiar womb of education, which paid off when I re-entered the job market. My second experience of unemployment was equally tough and unfortunately, I didn’t seem to have learned anything from my first experience. I was quite adept at internalizing the depression of the economy, fighting an internal battle about my value to society, until I again landed back on my feet with a new job.

Like many a sociologist, I have sought to understand life’s experiences by broadening the palette of my own mind and studying the phenomenon. Over the years, I have done a number of workplace studies, and invariably, even if the study isn’t about UN-employment, it becomes about unemployment or, equally difficult, about the challenges of working in dysfunctional workplaces. From my vantage point, most workplaces have a touch of crazy, and well-adjusted employees recognize this and maintain some perspective.

In one workplace study I did in six major corporations, examining the impact of flexible work policies on bottom line issues, two of the participating companies announced lay-offs during the course of the study. In one case, managers from around the country were brought into an auditorium, where the CEO announced the downsizing plan, charging the managers with the task of executing it. As you can imagine, the waves of fear and anger rippled throughout the corporation. In another company, the two top guys in the firm released a video which all employees watched at the same time, in which they sat comfortably in their mahogany wood-paneled office and speaking directly into the camera, announcing major lay-offs, and audaciously suggesting employees now had the opportunity to spend more time with their families. Seriously?! All the people I interviewed at that company were scrambling to figure out their next move, all second-guessing who was on “the list”. They were furious and they felt betrayed.

In another corporation, I was hired to conduct research on why people were leaving their jobs, and then the corporation announced it was downsizing thousands of employees. What were they thinking?! My work partner and I spent three years conducting phone interviews with 350 people about “why they were leaving” and invariably, the interview became a phone therapy session about how they felt betrayed by the company. In one unit, contract workers were brought in before the long-term employees left. Most (yes most) of the workers we interviewed in this unit confided in us that they were seeing a psychiatrist and taking Prozac. We just wanted to say to them, ‘Talk to your co-workers! You’re not alone!’ But confidentiality didn’t allow that…

One of the hardest hit groups is unmarried women, many of whom are mothers or caregivers. According to Liz Weiss and Heather Boushey, economists from the Center for American Progress, “The high unemployment of unmarried women, and particularly the 1.3 million unemployed female heads of household who are primary breadwinners for their families, is devastating to their financial circumstances and standard of living.” Unmarried women have much higher unemployment than married women. In October, 2009, 10.3% of unmarried women age 20 and over and 5.7% of married women were unemployed.

Losing a job usually means losing employer-supported health insurance, which is one reason why national health care reform is so critical. Weiss and Boushey report that there are an additional 276,000 children of unemployed single mothers who no longer have access to health insurance. Poverty rates for unmarried women are usually much higher than for married women (20.8 percent versus 6.2 percent of women 18 and over in 2008, the most recent data available), and poverty rates are probably higher because of growing unemployment.

At the policy level, we need an infusion of funds into job creation and job training programs, and better family policies to support women and men when they are “inbetween” jobs. Universal early childhood education, paid family leave and universal non-stigmatized family allowances would go a long way. At the personal level, it looks like those with more education experience less job loss, so this is another area that requires government policy and support.

Meanwhile, the next time some one – probably some man – asks me if I’m working or still working, I will ask for clarification. Are you asking if I’m unemployed? Do I look like I have a sugar daddy or momma? Do you really think I look old enough to have retired? Or maybe I’ll just smile and say “yes”.