by Mindy Fried | Jan 13, 2013 | arts education, arts education research, child development, dance education, early education and care, education, federal funding, music education, program evaluation, state budgets, youth theater

Over a year ago, I wrote a blog post about the importance of funding arts education. I’m still thinking about these issues, so here is Part Two: Save the arts because the arts save lives...

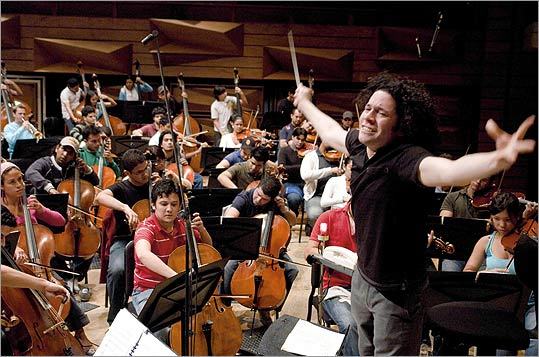

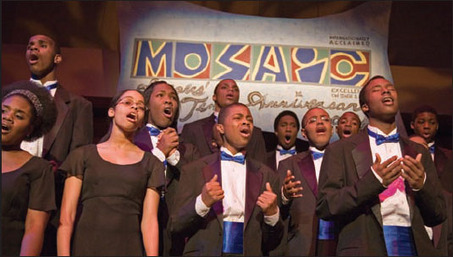

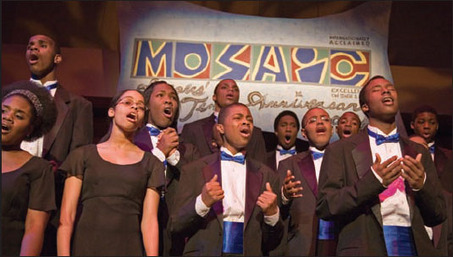

The arts – dance, theater, music, writing and the visual arts – have a powerful impact on children, opening the door to deeper knowledge and self-expression. I know from personal experience, and I have seen it in young people far and wide. While the current administration has said all the right things about arts education, this is sadly not enough, because federal, state and local policies STILL favor standardized testing and severely limit arts education funding. With all the concern about remaining competitive in a global market, this is precisely the time to fund arts education and allow our children to thrive.

I started taking dance lessons at age seven. For the first year, I did ballet, but only lasted one year because the teacher was nasty and the movements were too rigid for my soul. Instead my mother found a modern dance teacher, Seenie Rothier, a kind and ageless woman with a lean body and tight bun (and buns), who spoke with a raspy voice as she led her charges through endless contractions, swirls and triplets across the floor. Trained in Martha Graham-style dance, Seenie, as we all called her, had a penchant for the dramatic, and yet she was the most grounding element in my life. I always assumed that my family life was your average normal, and yet looking back, I have realized that it was a household rife with angry silence and disappointment. Seenie’s studio on Hertel Street in Buffalo, was just up the block from Kaufman’s Deli where they sold frosted brownies, and down the block from my grandparents’ working class neighborhood. It was my salvation. She recognized my talent, and by the time I was thirteen, had invited me to join a college dance troupe. Dance was my manna and still is.

While it is hard to “make a living” as an artist, I tried my best, working as a dance therapist in a psychiatric hospital and later, teaching dance as a resident artist in the Syracuse, New York public school system. I discovered the magic of movement as a source of expression for young children. Often in these schools, children were marched into the gym in single file, and told to remain quiet and respectful of the visiting teacher.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.

Dance is a healer, a universal mode of communication that is good for children. It’s natural. It’s great exercise. It wakes up the brain. It gives children an outlet. I have observed talented movement professionals use movement with children to help them learn science and math concepts. Dance can strengthen children’s emotional intelligence, and their ability to collaborate with others. And it can provide a form of discipline and order, when students are challenged to create dances that have beginnings, middles and ends.

A number of studies (see Critical Links) cite a positive correlation between dance experiences and nonverbal reasoning skills. One study demonstrated that “subjects” who were exposed to creative dance made significant gains in creative and critical thinking. And another study conducted with children with behavioral disorders found that when dance and poetry were combined, students’ were engaged and their social skills improved. Another study that promoted reading through dance to elementary children found that students improved significantly on all measures assessed by a reading test, including their ability to relate written consonants and vowels to their sounds.

The research on other arts modalities is equally strong, linking the study of theater to literacy, music education to improvements in spatial-temporal reasoning, achievement in reading, and reinforcement of social-emotional and behavioral skills. And classrooms that integrate the arts are a leveler for all students, including those with disabilities.

In my own research, I’ve found that teachers who implemented arts-integrated curriculum into their classroom had increased enthusiasm for teaching as they observed the positive response from students, both in terms of their attitudes towards learning, but also their ability to learn.

It’s time to broaden the policy dialogue and demand increased funding for arts education!

by Mindy Fried | May 8, 2012 | arts, depression, education, finding work, graduating from college, making choices, unemployment, women and work

As our daughter goes into her final year of college, I have begun to feel a sense of trepidation about what comes next. The seniors I taught this past semester are already going into panic mode as they face a very uncertain future. Regardless of all the internships and community service experiences they are accruing, there’s no avoiding the dour statistics for young college graduates. When one student came to me, asking for advice about applying for a consulting job that was way beyond her reach, I found myself counseling her about the virtues of working in a coffee shop. So what if she’s an international relations major!

My first “real” job after graduating college was working in a state psychiatric hospital. This seemed like a “natural” place to be, since one whole side of my family was riddled with serious psychiatric disorders. Between an aunt with agoraphobia who never left her house, an aunt and an uncle who had “manic-depression” (now called bipolar disorder, a much more “respectable” name), and a mother who struggled with clinical depression and alcoholism, I was quite at home working in an institution for people with severe mental health problems.

I had been a dancer for many of my young years, and my professional goal – if one could call it that– was to somehow combine my interest in helping people with my passion for dance. I lucked out, since the field of dance therapy was just emerging, and one of the first certified dance therapists in the U.S. was willing to train me during my senior year of college. When I graduated, the state psych hospital was hiring tons of young college graduates. This was the early ‘70s, when thousands of patients, people who had spent years, sometimes decades, living in inside the walls of state hospitals, were released into the community in a move to “de-institutionalize” them. The motive was humanitarian, but the upshot for many of the patients was downright cruel. Nonetheless, it did mean that a lot of my friends and I had jobs.

I was hired as the institution’s dance therapist – and worked with people who were still living “inside” the institution, as well as out-patients that were being transitioned into a day treatment program. I fell in love with schizophrenics who were smart and spoke in metaphors that seemed poetic and deep. Because I was a professional dancer in a mental hospital, many of the institution’s rules did not seem to apply to me. Or at least that’s what I thought and how I behaved… More than once, I led a group of patients in a snake line through the hallways, and we seemed off-limits to criticism, as this “crazy” activity was “therapy”! It felt downright revolutionary!

While this experience – working in an institution – wasn’t where I “landed” professionally, it was nothing short of a profound experience. I will never forget one of my out-patients, a diminutive woman named Ruth, who had spent her entire adult life imprisoned in the psych hospital. Ruth held her body like a tight fist, and stood all day, rocking rhythmically back and forth. I still feel teary when I think about her. There was another man who is seared in my mind: a tall, broad gentleman in a perpetual cowboy hat who people called “the Captain”. He was a man of few words, and those words were garbled, but he had a jovial demeanor. One of my most glorious days with him was when I took him for drive in the country, with two other patients. Outside it was minus forty degrees; but inside the car, with sun shining through the windows, it felt warm and protective. He said little throughout this drive, just smiled…

By the time I had been hired to work as a dance therapist at the state psych center, sociologist Erving Goffman had already published his seminal book Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. One of Goffman’s greatest contributions was his critique of what he called “total institutions”, which included mental hospitals and prisons. Goffman argued that total institutions had a high degree of regimentation, and an elaborate privilege system. He described relations between staff and patients (or inmates) as caste-like, with detailed “rules” of deference and demeanor. One of the my favorite co-workers at Hutchings, a friendly and clever guy named Willie who was the janitor, surely understood Goffman’s analysis when he changed his first name from Willie to “Doctor”. Whenever anyone wanted his services, they would yell “Doctor” and he came running with a smirk on his face.

I knew nothing of Goffman while I was working in an institutional setting. But now, as I reflect on my first post-college job, and after studying this brilliant sociologist in graduate school and using his analyses in a class I now teach about the sociology of aging, it all comes back to me. First, I lived what Goffman described and then I was able to understand his theoretical frameworks, drawing upon my own experience. As my father used to say, everything we do in life accrues and has meaning. This has to be true, as well, for college students who are graduating to a lousy economy and a dearth of employment opportunities that “fit” with their majors.

Despite the draw of my first job, I realized within a year that I wasn’t going to last. I was too young, too inexperienced and too critical of the institution to stay. While I found the out-patients I was assigned to counsel interesting, I had no real training. And even though I was a good listener, I fought back tears every time a “client” expressed sadness or joy. What drove me to work at this state psych hospital – working with really troubled people – ultimately became the reason I had to leave. Ultimately, it wasn’t the right fit, even though it seemed right at the time. With a far more robust economy than we have today, I had saved up enough cash that year to travel in Europe for nearly a year, and that’s what I did!

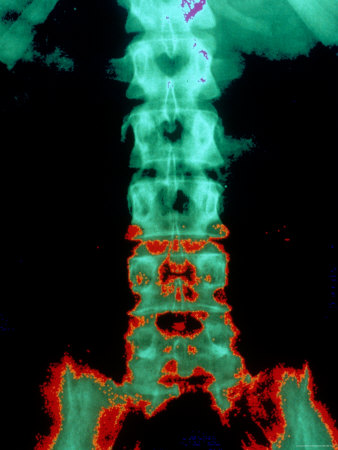

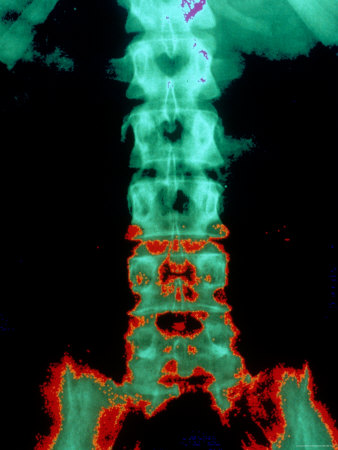

While my career as a dance therapist came to a halt, my original passion – dance – continued to be my life-line for decades until around ten years ago, when I experienced a serious injury. For a year, I was in persistent pain and could barely move, much less dance. With the sudden loss of the activity that centered me and gave me such joy, I plunged into a deep depression and felt overtaken by panic, fearful that I would never heal. Like many back-pain sufferers, I bounced around to various practitioners, many of whom got frustrated with me because I wasn’t getting better. In one pain clinic, a doctor yelled at me, saying that I was fine. In another back healing program, a doctor challenged ME to figure out what the problem was, because she could not. Other practitioners told me that I wouldn’t heal if I stayed depressed and anxious. A true chicken and egg problem…

During this time, I had a glimpse of what my patients from many years before had experienced. The one person who comes to mind, in particular, is a young woman who was around my age and had participated in an ongoing dance session I held for outpatients. I never knew what her story was; only that she was struggling with depression and had obviously spent time in the hospital itself, which meant that she had been in the role of “patient”, complete with the dehumanization that comes with that experience. She came up to me after one of our dance sessions and thanked me, saying it was the one thing in that setting made her feel “normal”.

How are young, college-educated people dealing with this lousy economy, saddled with debt and poor prospects for a job? A number of young people I know are living at home, and working in unpaid internships that they hope will lead to a paid job. I know one young person who dropped out of college in her freshman year and learned how to do organic farming. Now she’s running a business where she creates peace gardens for interested clients. And I know another young person who couch-surfed for a few months, and then got a job sailing someone’s boat down to the Virgin Islands. At one point, during an intense storm, he wondered if he was even going to make it… I can imagine that he is not the only one feeling that way.

Over time, I have come to realize that we humans are drawn to different types of work at different stages of our lives, and often there is a reason. I happened to work at a mental hospital because it grabbed me emotionally – and that’s where there were jobs. But even then, when the economy was decent, that first job out was hit or miss. The thing that sustained me was dance. It continues to be my way in, and my way out. When I think about my own daughter – and all the young people I encounter these days – what I wish for them is the courage to follow their passion, and then feel okay about whatever job or internship (or whatever) they find, knowing that those things may not be the same thing. At least for now.

by Mindy Fried | Feb 15, 2012 | blacklisted, education, House Un-American Activities Committee, HUAC, organizing, prejudice, protest, resiliency, social justice

I was on the treadmill at the gym the other day, frantically trying to undo a day of sitting and staring at my computer, when a casual “gym friend” joined me on an adjacent treadmill. She noticed that I hadn’t been there lately, and wanted to know why. I don’t know her well and could have manufactured some story, but she had always been so warm and friendly, so I decided to tell her the truth, that my 97-year-old dad had just passed away. Her response was immediate and kind, as she empathized with how hard it is to lose a parent. Then she looked up to the ceiling of the gym, and as I followed her gaze, wondering what had stolen her attention, she said in a reassuring voice that he was in heaven now, and then looked back at me with a smile. Not knowing how to respond, I smiled wanly and increased the incline on the treadmill. I wish I believed that he was in heaven and as my partner says, I hope to be happily surprised…

She then asked about the funeral, and I explained that we had it right away because I’m Jewish and that’s what we do… Apparently, distracted by the realization that I was a Jew, she then said that she had many arguments with her Catholic friends who believed that “the Jews killed Christ.” (Wait a minute – where did that lovely empathy go?!) Just as I was thinking about an exit strategy, she came back to earth and said, “It’s crazy that people of all faiths don’t get along.” And as I was mentally excusing her for that detour, she added, “except for the Muslims”. Again, I was hooked, and as I looked at her, I know I must have appeared surprised because she looked back at me with a slightly uncomfortable smile. And then went on to say that she worried that Muslims – presumably all Muslims – were terrorists. Wasn’t it time for me to leave the cardio area and work on my abs or something? But no, I couldn’t leave now, as this was a “teachable moment.”

I said that the media would like us to believe that all Muslims are terrorists, but most Muslims are peaceful people. And she asked me, didn’t I think that the “Koran incites Muslims to commit terrorist acts?” I replied with certainty, with whatever knowledge I have accumulated since 9/11, that that was untrue.

This really bugged me, a kind-hearted, well-meaning person swallowing Fox News whole. And it really upset me that the media is so compelling that good people can believe such nonsense.

I learned the hard way from my father not to run away from difficult conversations and to stand up for my beliefs. In the 1950s, and again in the 1960s, he was called before the Senate House of Un-American Activities (HUAC) to answer the now-infamous question, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party (CP) of the United States?”. The first time he was subpoenaed before the committee, he challenged its legality. And the second time, he used the first amendment, declaring his right to freedom of speech. As a result of the first committee hearing, he was “blacklisted” from work in the U.S., and ultimately sold life insurance for 15 years through a Canadian firm. He also became a prolific playwright, writing about his experiences within the labor movement in attempt to give voice to working people.

It was not until I was well into my 30s that my father admitted to me that he had been a member of the CP, but had wanted to protect me in case the FBI approached me with that question. That might seem like crazy-thinking, but the FBI actually did follow my father – and consequently, our family – for half a decade, employing agents to observe meetings where my father spoke, reviewing documents he wrote, including plays and memoirs, and even observing the fall-out we experienced in our family, as a result of being persecuted by the government.

When I left for college, my father warned me that I might be approached by an FBI agent, asking about his political activities. At the time, that seemed ridiculous, the product of narcissistic, paranoid thinking. But in my junior year, a guy from the Dance Club – in which I was very active – began asking me questions about my dad. Through some research, I discovered that he had been working out in California, trying to sabotage the Cesar Chavez grape boycott. I realized that maybe my father’s paranoia wasn’t so crazy after all. Using the Freedom of Information Act, my father ultimately received roughly 5,000 pages of FBI notes, with many of the words redacted (meaning crossed-out!), supposedly to “protect” the identity of the agent who was following him. I spent hours pouring through these files a number of years ago, and was stunned to read that the FBI knew that my sister and I were being ostracized by our so-called friends because of my father’s political beliefs, and that my mother lost many dear friends and family members to the fears they had about being associated with “a Communist family”. You can read more about this in Colin Dabkowski’s article in the Buffalo News:http://www.buffalonews.com/spotlight/article727714.ece

After my mother died, my father told me another reason why he left the Communist Party. He didn’t want that admission to have negative repercussions on his CP colleagues and friends. He was a working class Jewish man who had strong convictions and was loyal to his friends, risking a lot to stay true to them. He wasn’t trying to overthrow the government, although he was challenging an economic system that, even more so today, creates haves and have-nots. He was simply a very effective labor organizer who mobilized workers around issues of wages and benefits and fair treatment on the job. In doing this work, he was simply executing his first amendment rights to speak out about his beliefs. I believe that the world was a better place because of people like him.

So what to say to my friend at the gym, who seems to have drunk the kool-aid of misinformation in the right-wing media? What to say to many of my fellow Americans who are now stumped about whether to support a wealthy businessman for President whose personal and political interests are intertwined or an evangelical politician who would happily turn our country into the United Christian States?

There are many ways to fight disinformation and work for a better, more equitable world, through organizing, writing, teaching, and just speaking to friends, colleagues and acquaintances. And we must not be afraid to do so.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.

Little did they know that the new visitor was about to tell the children to jump up and down like popcorn, express their joy and anger through finger dances, and shout as loud as they could, using only their eyes or feet. There was always one child in every school who attached her- or himself to me, following me around, sometimes sitting on my lap or holding my hand as I moved through the room. Sometimes I imagined that what this child really wanted was to crawl into my womb for safety. And there was always the wild child. Sometimes teachers warned me about him or her, and other times, I learned through my own encounters. If teachers were observing – they rarely participated – they might speak with the child in a stern, warning tone or pull the child away for time out. But when I could, I intervened and said ‘no, it’s okay’, because I could usually figure out a way that that child could use movement to express herself.