by Mindy Fried | Jan 31, 2011 | family, loss, value of caregiving work

This past weekend, I visit my nearly 100-year-old dad who is now in home hospice in an assisted living facility. With several major organs failing, he remains the perennial survivor. As a literary guy, he always used to quote Dylan Thomas, saying: “Do not go gentle into that good night.” And he continues to hold on…

I leave his apartment after my visit, feeling both a sense of relief as well as a deep sadness, even though I know I will see him in two weeks (assuming…), and that meanwhile, he is being well-cared for. As anyone who has taken care of an older person knows, caregiving is stressful, and caregiving from afar has its special stresses.

The ride to the airport is straightforward in this small city. It’s always a bit nostalgic as I pass by my father’s old house, where he continued to live alone up until two years ago, when we moved him into assisted living. As I pass the old street, I call my husband to let him know my plane is delayed, ignoring the state’s anti-cell phone law. (Okay – I know it’s unsafe, but I was at a stoplight!). And then it happens – BOOM!

I feel my car being hit from behind. I say matter-of-factly, ‘Oh my G-d, I was hit. I’ve got to go.’ And then my car gets hit again! I manage to move into the next lane, and this car keeps charging forward, hitting the car that was in front of me.

I jump out of the car, realizing that I’m okay, but see that my rental car is not. The driver responsible for all this reckless bumper car action is an older man, probably in his 80s. I tell him to pull over and then follow him. Turns out that he had put his foot on the accelerator instead of the brake! He claims that his foot was stuck. He is on his way to visit his wife’s grave. She had died six years ago, and he has borrowed his son’s car to get there.

The front bumper on his car is mottled, but aside from being stunned, he isn’t injured. Of course, what happens with him and his son is their next chapter, not mine, and I can only imagine. (Will the man continue to drive? With the son lend him his car? I hope not…) With this crash, we are connected by our humanness – this elderly man who is grieving for the loss of his wife, and I, who am grieving for the gradual loss of my father.

But there isn’t time to meander. My flight is leaving soon. I get advice from the rental car company about information I need from this guy, and after well wishes, I move on, driving down the highway, with half of the bumper hanging off my rental car.

As I enter the airport roadway, I call the rental car company. Like relay racers, they are ready and waiting, as papers fly between us and I gather my luggage. Running to the ticket counter, I arrive out of breath, only to be told that boarding for my plane is closed, and it’s too late to get on the flight. I plead for the airline worker to do something, sputtering fragmented sentences about my dying father and my accident. Just an instinct to use a sad story to manipulate authority… And then out-of-the-blue, another kind airline worker intervenes and calls the gate and tells them to hold the flight for me. Just for ME!

They tell me to HURRY to the gate! I get through security as quickly as one can get through security, run up to the gate, heart beating wildly, and apologize to the airline worker for holding up the flight. She looks at me whimsically, and says with humor, “Oh yeah, the whole flight is waiting just for you!” It turns out that they have not even started to board the plane. In fact, I have about 20 more minutes to wait. With that relief, I blurt out my story again, and this time, start to cry. For a moment, she looks me straight in the eye, and then she wraps her arms around me, saying, “I’m such a softy. I feel like crying with you!” And we do. Me and an airline employee!

Today, the airline gave me a $50 credit for the “inconvenience you recently experienced with us.” So thank you, Jet Blue worker and thank you, Jet Blue.

But most of all, I am grateful that in the midst of the challenges of caregiving, I have encountered people – strangers – with whom I connect, who gracefully help to diffuse those challenges.

by Mindy Fried | Jan 21, 2011 | child care, early education and care, family, military family policies, parental leave policy, policy, work and family balance

A number of years ago, I was invited to the Pentagon to talk about a work and family study I was conducting. Anyone who knows me may find this fact pretty incongruous. But I was intrigued to find out about the human resources side of the military. Given my history of antiwar and women’s rights activities – and the fact that my father had been subpoenaed to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s – I fully imagined that I wouldn’t make it through the security screening. But, to my surprise, I sailed through. I found myself being chaperoned through dingy hallways to a very nondescript office for a meeting with a powerhouse of a woman who headed up programming on family supports for military “members” and their families.

Over the next two years, I worked with her and a real live Colonel, a kind and gentle soul who was an expert on domestic violence issues in the military. Our work together focused on assessing how well various military family support agencies were able to collaborate. Their “mission” was to support families through the challenges of dealing with deployment and loss.

I initially felt like a fish out of water working within this institution. But I soon connected with the human dimension and discovered that within the military, there are people from incredibly diverse backgrounds – including political perspectives – who really care about people’s well-being. I also learned that the military has far more progressive family policies than governmental policies in the civilian sphere, which rely on a hodgepodge of precarious private and public funding to service those in need.

I discovered, for example, that the military provides high-quality, affordable and accessible childcare in which early childhood teachers are paid good wages. According to Gail Zelman and Susan Gates, researchers at RAND,

“While there are no easy or obvious solutions to the childcare problem, policymakers can look to an unlikely source from ideas about improving childcare: the military. The US Department of Defense (DoD) has succeeded in optimizing the three key aspects of child care delivery – availability, quality and affordability – a juggling act unduplicated anywhere else in the country. The system currently meets around 60% of the assessed need, serving about 176,000 children 6 weeks to 12 years old in 900 centers and in 9,200 family child care homes nationwide. (Family child care homes are usually run by military spouses.)”

Let’s be honest here: The military’s desire for high levels of productivity and commitment among its members – and the need for support from military family members – are the drivers underpinning military support for these policies.

So what can policymakers learn from DoD’s experience, ask researchers Zellman and Gates?

“The clear message is that affordable, high-quality child care requires a system level commitment to quality, as well as incentives and funding to make it a reality.”

In contrast, our “civilian” child care system in the U.S. is underfunded and suffers from lack of quality, which can largely be attributed to low wages and inadequate support for its workers. In fact, the turnover rate of early childhood teachers in the U.S. is between 25-30%. Research points to a “turnover climate” which affects overall program quality. One study found that highly trained teachers (BA level or higher with specialized training) “were more likely to leave their jobs if they earned lower wages, worked with fewer highly trained teachers and worked in a climate with less stability.” (Whitebook, at al, 2001). Therefore, worker retention is linked to the stability of the program and ultimately, to higher quality.

In addition to high quality, affordable child care, the military offers paid parental leave and universal health care. Ironically, when progressives promote these policies at the federal (civilian) level, conservatives cry ‘socialism!’

In a memo entitled, “For Our Air Force Family,” Lieutenant General, USAF, Assistant Vice Chief of Staff, Joseph H. Wehrle, Jr., says,

“The United States Air Force is committed to taking care of its own. Steadfast, homefront support is provided to family members by the Integrated Delivery System… As always, we remain One Force, One Family.”

in the military, the credo – “We take care of our own.” – is motivated by the belief that this will support “readiness” for battle, increase productivity, reduce turnover, and ease the process of leaving one’s family behind to put oneself “in harms way” around the globe.

Without such immediate drivers in the corporate or non-military governmental sphere, it is hard to make the case – or as human resource professionals would say, the business case – for progressive family policies. But we don’t have to only look to Europe for inspiration around family policies; we can look to the U.S. military to find some of the most progressive policies in this nation. Don’t we all deserve them?

by Mindy Fried | Jan 5, 2011 | family, knitting, value of caregiving work, women and work

My grandmother survived the pogroms of Eastern Europe, a solo journey to America at age 13, and my grandfather, who is one of the grumpiest men I’ve ever met. But until the day she died, just shy of 100 years old, she was an avid knitter, spewing out afghans, sweaters and socks to keep her brood of nine children clothed and warm. Lucky me received one of her gems at age 20, a very tidy little blue cardigan that I have to this day.

I never really thought of my grandmother when I started to knit. It just seemed like a fun thing to do with my daughter, with whom I used to “co-knit” scarves that were more about process than product.

Several months ago, a friend, whom I will call my “knitting guru”, pulled together a group of women to knit caps for a special neighbor friend who was going through chemo. I was driven by the mission and inspired by the camaraderie of the group, and managed to make several hats for our friend. They were full of flaws, but beautiful, nonetheless (if I do say so myself!). We all read Kyoko Mori’s book, “Yarn: Remembering the Way Home”, a memoir that is framed by lessons she learned from her knitting experience. I was most touched by her recognition that mistakes are okay. I realize that this sounds pretty basic! But somehow knitting lends itself to metaphors that speak to the heart. For example,

* Individual pieces of yarn weave together and create something beautiful and new.

* Sometimes, when you make too many mistakes, you just need to undo what you’ve done and start over.

* When a ball of yarn gets really knotted, it takes a long time to undo the knots.

See what I mean? Once I got the knitting bug, I discovered a world of knitting addicts (we are everywhere!) who find pleasure – as do I – in color and texture, and creating usable objects that people want to wear! What a concept! I also discovered that the process of knitting is meditative, relaxing, invigorating, all-consuming, jitter-reducing, anxiety-protecting, and creative. Once you’ve gotten past stage one, you can actually talk and knit, which is also incredibly satisfying…

When I told my college-age daughter I had started to knit again, she expressed concern that I was – in short – getting old. Despite my arguments that knitting was the “new cool”, she had conjured up images of me as a doddering old grandmother, content with my yarn and needles. Alas, when she saw the hats I was making, she put in a request for a sweater, and lo and behold, she started to knit too!

My first three hats went to my friend who had lost her hair. The next three were sold to neighbors during an “open studio” event, in which people stroll through the ‘hood and view art on display in and around people’s homes. These folks actually paid money for my hats! The next batch went to my family. My father – nearly 100 years old – had moved to assisted living and I had started flying to visit him every other weekend.

I made four hats for the cousins who house me when I’m visiting him. They call them their “Mindy’s.” I’ve made five hats for my immediate family, including my husband and sister. And I finally made a hat for my father, who, after seeing all this knitting action, said he’d like “a Mindy” for himself. I also made several hats for my daughter’s friends and a neighbor. The next few hats will be for the amazing people who care for my father nearly 24/7, keeping him alive with their love and attention.

When I think I’m done making hats – after all, there are a lot of other interesting things to make – someone else puts in an order. And I’m grateful for it…

by Mindy Fried | Nov 21, 2010 | child care, early education and care, family, parental leave policy, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, work statistics

Yesterday, I shared a long plane ride with a Japanese woman who was coming to the States to visit a friend. She patiently helped me try to track down an old Japanese friend via Google. Yes, there was WiFi on board; yes, Google in Japanese is very cool; and no, we were not successful in tracking her down! But more importantly, we talked about work and family issues, as she described the gendered division of labor in Japan. She is employed as a translator, but took a 10 year hiatus from her paid work – actually quit her job – to care for her son. This is typical, she said, among women “in her generation.” (After our conversation I calculated her age as around 43.)

In his book, The New Paradox for Japanese Women: Greater Choice, Greater inequality, Japanese economist Toshiaki Tachibanaki presents a gendered analysis of the Japanese economy. He reports that while Japanese women now have more choices in their careers than in earlier days when their education consisted of preparing them to be “good wives,” they now face job discrimination, sexual harassment and wage inequalities on the job. My new Japanese airplane friend commented that her husband wanted her to stay home with her son, telling her that it was the most important thing she could do. He, on the other hand, was working 12+ hour days. When I asked her if he was “able to” spend time “at home,” she winced and said that he did play with their son sometimes, but didn’t do any housework or cooking.

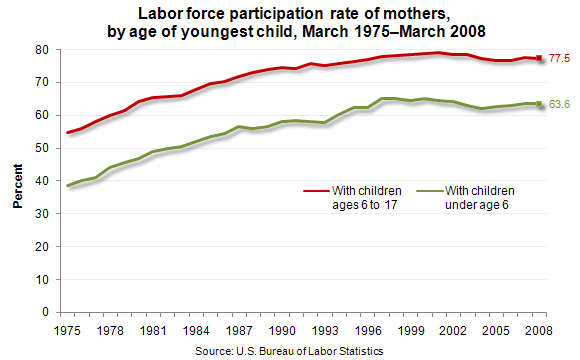

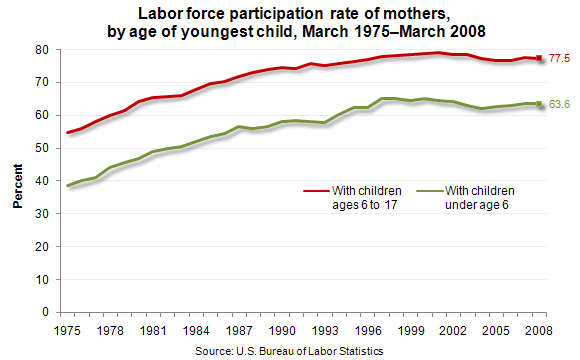

She was surprised to hear that over 75% of American mothers of school-age children work for pay. In Japan, nearly half of all women work in the labor force, but Japanese women earn less than half of what men earn. So it’s no surprise that women take on the brunt of the caregiving responsibilities, simply from an economic perspective. By the way, the gender wage gap in the US also is a significant problem, particularly for mothers, albeit less stark than in Japan.

She also described the dissolution of the extended family in which multiple generations lived together. Without a grandparent to do childcare, women in Japan have a harder time sustaining full time employment.

While we didn’t dive into a discussion of childcare policy in Japan, her observation got me thinking about the meaning of community and the gendered division of labor during my childhood years in the 50s. The 1950s in the U.S. are portrayed much like my Japanese friend’s description of contemporary Japanese culture, with the general assumption that mothers’ most important work was to stay at home with their children.

But what did staying at home actually mean in 1950s America? I know from personal experience, as a child of the 50s, I spent hours playing on the street with my friends. Whether it was kickball, dodgeball, relay or two-person races, or making up plays, we kept each other busy (on the street, as opposed to off the streets!). When I wasn’t in school or hanging out with my buddies on the street, I was taking dance classes or piano lessons. And when I wasn’t in school, on the street or at a lesson, I was firmly planted in front of our black-and-white TV, watching “traditional family life” in shows like Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best, and Ozzie and Harriet. While my mother was a “stay-at-home” mom, like the majority of middle-class mothers in that era, she and I didn’t spend a whole lot of time together because, frankly, I had other fish to fry!

Despite the glorification of family life in 1950s America, believe it or not, mothers today spend about the SAME amount of time as the 50s and 60s moms who did not work outside of the home! Family sociologist Suzanne Bianchi found that while the number of children with mothers in the paid labor force has gone up considerably between 1965 and 2000, there has actually been a slight INCREASE in the amount of time moms are spending with their children over these years now – from 10.6 hours per week in 1965 to 12.9 hours per week in 2000. Contemporary dads also spend a little more time with their kids these days, from 2.6 hours per week in 1965 to 6.5 hours per week in 2000.

So what’s the deal? Well it looks like a number of factors have converged to create this new reality, even though mothers and fathers spend a lot of time at their paid jobs. First of all, the work of the “at-home” mother has been greatly altered by technology and fast food. Meal preparation – especially when it comes from a takeout joint, comes out of a package, or pops out of the microwave oven – takes less time. Mothers are also spending less time cleaning the house, compared to a few decades ago. Dust bunnies prevail! And actually, fathers never spent a whole lot of time cleaning the house anyway, so no big change there.

But equally important, the notion of good parenting has shifted over the years from more hands-off to more intensive, involved parenting. From playing classical music to your in-utero fetus to knowing all your kids’ teachers to coaching her Little League team to texting daily with college age kids, the contemporary notion of “good parenting” has been redefined as engaged parenting. Based on the research, it seems that mothers who work outside the home want to “protect” the amount of time they have with their children; ergo, spend as much time with them as possible.

In her study of nurses who work night shifts, Anita Garey found these women chose night hours so they could maintain the notion of the “ideal mother” who was available to meet during the day with her child’s teachers, bake for the bake sales, and show up at school events. All this came at a cost: sleep and personal care. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild called this phenomenon the “time famine.” Bianchi argues that the increase of mothers in the paid labor force, at least in two-parent families, has shifted some of the caregiving responsibility to fathers, commenting,

“Perhaps most controversial, women’s reallocation of their time probably has changed men. The increase in women’s market work has facilitated the increase in women’s involvement in child-rearing, at least within marriage.”

Clearly, the economy is the driver in the U.S. and other parts of the world, creating an imperative for women to participate in the paid labor force. But women, like men, derive meaning from paid work, and the women’s movement of the 1970s – while rarely mentioned these days – had a powerful impact on women’s sense of entitlement in the workforce.

While we are not battling the level of tradition that exists within Japanese culture, we have a long way to go to achieve equity, particularly for mothers in the paid labor force.

To achieve real equity in the labor force, we need concrete changes in government policies that promote and protect wage equity for women, and protect against gender- and parent-based job discrimination. We need a paid parental leave policy, and support for shorter work hours so that parents of young children can choose to gradually return to full employment after taking a parental leave from the jobs. We need universal child care so that all young children have access to high-quality early education and care, and not just those in families that can afford it. And we need universal health care, so that workers are not reliant on a job for their health insurance. That’s too dangerous in this economic climate, and even with employer-based insurance, there is too much variability in the type of care provided.

Tall order? Maybe, but we need a comprehensive set of solutions to achieve “good parenting” in this age of work-family imbalance.

by Mindy Fried | Nov 2, 2010 | family, parenting, value of caregiving work

When I first visited my father’s assisted living facility, some guy shuffled up to me and asked, “Am I going to dinner or lunch?” I managed to reply as if it were the most normal question in the world, but felt like I had landed in the Twilight Zone. Over the past year, I’ve grown accustomed to hearing just about anything that anyone says. For example, over dinner this guy I really like, Harry, whispers to me in a conspiratorial tone, “How old is your father?” I tell him, for the umpteenth billion time, that he is 97-years-old. And as if this is the first time he’s heard this news, he responds with shock, telling me that my father looks so young! Harry tells me he’s 90 and then turns to his girlfriend, Millie, who is only 80, and says, “Isn’t that right?” She replies patiently, “Yes.”

Lately, I’ve been spending a lot of weekends with my father, as his health is rapidly declining. Despite the fact that he’s officially in home hospice, he is enjoying lunch and dinner visits with friends, and he goes to exercise class every day at the facility. On Sunday, he was too tired to go and as he was contemplating what to do, admitted that he felt guilty for not going. He’s not even Catholic!

I started looking forward to joining him at his morning weight exercise class, where a young and very perky teacher gets things rolling with balloon volleyball, a “game” I associate with young children. It’s pretty straightforward. She stands in the middle of the circle of residents who are all seated in their chairs or wheelchairs, and she flips the ball around the room, making sure everyone has a turn. Some are very cautious with the balloon; others give it a big whack and laugh out loud.

I’m amazed at how long folks enjoy playing this game. Even though the class is called weight exercise, this weightless balloon game constitutes about three quarters of the class. I get into it, mixing up my “moves” with actual hard punches and an occasional soccer head hit, which is entertaining for this crowd. Later in the dining hall, I see some of my volleyball team and we have a special connection.

For a moment, I imagine what it would be like if I actually lived here. And then I realize that by the time I had to live there, I probably would have some fairly significant things missing, like my ability to move freely and maybe even my mind.

Of course, all of this fun and games is punctuated by an undercurrent of failing health, as residents notice who is not showing up at bingo or as someone is rushed out of the building on a stretcher. Harry often asks me how my father is doing, calling him “Mack” even though that’s not his name. His girlfriend reminds him, with a touch of annoyance sprinkled with humor. He says to me hopefully, “Mack looks really good, just the same as when he first moved in, doesn’t he?” The fact is that “Mack” isn’t doing too well at all, but I don’t have the heart to tell Harry.

I feel grateful that we found a place where the staff are kind and mostly competent, and the residents aren’t all out-of-it. My father first moved in after a serious fall and it was evident that he could no longer live independently. He was willing to move, but angry just the same, and at times, said he had to get out of there. He felt alienated. These weren’t “his” people. He assumed they weren’t into what he was into, like theater, literature and politics. He certainly wasn’t a bingo kind of guy, either, which is one of the big pastimes in that place. But over the year, he has succumbed to “gambling”, as he calls it, and takes pleasure in being in the company of others. Happy hours – which include cocktails like Margaritas served in little paper cups- seem to tickle his fancy.

It’s harder for him to follow conversations, and there’s no point in bringing him to the theater now, because he is now legally blind, and anyway, he’d have trouble following the action and would end up sleeping through the whole thing. Not to mention that getting there and back would be very hard.

How do we want to live the “end-stage” of our lives? The research says that a critical factor that keeps people going – no surprise – is engagement in meaningful activities. Another important thing that keeps us alive is giving to others. The bottom line is that we all need to feel that our lives have meaning, that were contributing to society, more broadly, or to our friends and loved ones at a personal level. We all want a life well-lived.

But how do we maintain engagement? Perhaps we need to ask: What are we doing now in our lives that will sustain our sense of engagement? What kind of networks will we still have if and when we live long? How do we maintain a network of younger friends? Because chances are, all or most of our contemporaries will be gone if we live very long. And what about housing? My father lived on his own until he was in his mid-90s, resisting our efforts to consider safer options. We could never imagine him in an institutional setting, but we’re lucky that he can afford a decent assisted living facility and extra care, as needed. But what about the thousands of elders who don’t have the resources to live this end-stage of their lives surrounded, as he is, with dignity and love?

I leave my weekends with my father feeling exhausted but glad I was there with him. And I can’t help but wonder whether I’ll live to his age or older, and if I do, what kind of options will be available for the old woman I become.

by Mindy Fried | Oct 13, 2010 | child care, family, parental leave policy, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work

A sociologist buddy of mine just told me that she may be using my book on parental leave in a new class she’s teaching (Taking Time: Parental Leave Policy and Corporate Culture). While I should be overjoyed, I am not. Why? Because the book is 12 years old and it’s sadly as relevant today as it was twelve years ago!

Taking Time is based on an ethnographic study. In other words, I went native and hung out for a year in a financial services corporation I called Premium, Inc., studying its corporate culture. I wanted to understand how the culture of the workplace affected employees’ attitudes towards the company’s generous parental leave policy and ultimately, who used it.

I happened to be doing this study right after the passage of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA.), which was the first bill President Clinton signed in 1993. The bill mandates employers to allow their workers – women and men – to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to parent their newly arrived baby (biological or adoptive). This federal policy provided basic rights to Premium employees, in addition to the company’s own parental leave policy.

To my dismay, I found a strange and insidious blend of economics and culture that seriously undercut the use of parental leave policy at Premium. Of the 143 parental leave takers I interviewed, 140 were women and 3 were men! Women in high-level positions barely took leaves. In fact, only two female vice presidents took five weeks; the three senior female managers took five, nine and 10 weeks respectively. As one female senior manager said,

“Old-time management in the company still has an old mind-set about about women and work and family…The women who generally get to the higher top are the women who don’t have the children. You have to sacrifice something to get there.”

Not a single male senior manager took a parenting leave. Instead, new fathers tended to take 2-week vacations after the arrival of their new baby. One male manager I interviewed told me,

“It was simple economics. I was going to work full-time and (my wife) was going to work part-time. We joke about her job being a hobby because she’s hardly covering the cost of daycare.”

Most men facing new parenthood didn’t even consider taking time away from their jobs to parent a newly arrived infant, because they were worried their careers would suffer. For them, the cultural norms of the workplace mitigated against taking time to do what is still considered “women’s work”. Simply put, for both high-level female and male managers, babies and briefcases didn’t go together. This cultural norm trickled down to the organizational culture…

The largest group of workers who used the leave policy were women in non-management positions. Professional non-management women took an average of 10 weeks leave, two weeks less than the 12 weeks allowed by the FMLA! And nonprofessional women – women who earned less than those in professional positions – took an average of 8 weeks, with half taking 7 weeks or less. These women simply couldn’t afford to take longer leaves. Unless they had family lining up to care for their babies, much of their time was spent worrying about setting up quality, affordable childcare. This short leave-time falls far short of the six-month leave that T. Berry Brazelton, child development expert, recommends to support parent-child bonding.

In a 2009 study of current leave-taking practices, researchers found a a similar picture. There has been a very small increase in the amount of leave-time taken in the birth month (5.4%) by “highly educated and married mothers” and an increase of 13% in the next two months (Han, Ruhm and Waldfogel, 2009). Single mothers, on the other hand, are less able to afford unpaid leave. And fathers continue to take extremely short leaves or none at all.

This data confirms what I found in my study 12 years ago: that uppaid leave policy discriminates against those at the lower rungs of the income ladder who cannot afford to take longer leaves. With the absence of a mechanism to replace workers’ wages during the leave period, non-management female employees shorten their leaves; management employees take short leaves; and men don’t take parental leaves at all.

While lower paid workers would be the most obvious beneficiaries of paid leave, in fact, ALL employees would benefit from such a policy. The U.S. is the only wealthy nation in the world that does not offer parental leave, according to political scientist Janet Gornick, who conducted a cross- national study of parental leave policies.

“The United States has the least generous parental leave policies of all 21 economies compared in the study. We pay a high price for our meager policy, because parental leave improves the health and well-being of children and their parents, and paid leaves provide families with crucial economic support at such an important time.”

Gornick and her colleagues report that European countries, led by Finland, Norway and Sweden, rank far ahead of the United States in providing guaranteed parental leave, with Sweden ranking highest for gender equality and parental leave practices. Germany also offers a generous paid leave policy, and four countries show high levels of both generosity and gender equality: three Nordic countries (Finland, Norway and Sweden), and Greece.

We have a long way to go in the U.S.! California finally passed paid parental leave legislation in 2002, and the U.S. military even offers paid leave to its members. But a recent effort to extend paid leave to civilian employees got stuck in the Senate. And other initiatives to create paid leave through “baby unemployment insurance” – in which some small portion of the state unemployment insurance fund would go towards a paid leave fund – has hit a wall, given high employment rates.

Nonetheless, the issue will not go away for the thousands of mothers and fathers around this nation who want to spend more time with their babies.

It may seem counterintuitive to push for paid parental leave in this economic crisis, especially as people are being laid off from their jobs. You might argue that laid-off workers have more time to hang out with their kids anyway. And besides, why would employers want to add incentives for their existing labor force to take time away from the job? But those laid-off workers will return to the workforce when the economy improves, and those employers should care about creating humane work environments that don’t burn out their workers. And why shouldn’t we join the rest of the Western industrialized world in providing social policies that support mothers and fathers in the workplace?

Without a federal policy that provides the foundation of support for leavetaking, I fear that we will continue to see the patterns of leave-taking I found in my study twelve years ago. And that’s just not fair.

Meanwhile, my sociologist buddy asked if I could come to her class to talk about my book. I wish it were old news…