by Mindy Fried | Apr 1, 2015 | adventure, applied sociology, careers, finding work, gender, making choices, program evaluation, race, social science research, sociology

When attempting to transform communities through social policy, it is imperative to not only understand what the social problem is, but also how and why it exists and persists. Trained sociologists have indispensable tools for this type of applied work. – Chantal Hailey

In my last blog post – Choosing Applied Sociology – I referred to a 2013 article in Inside Higher Ed in which Sociologist Roberta Spalter-Roth, from the American Sociological Association, comments that “In sociology, there is close to a perfect match between available jobs and new Ph.D.s”, if you take into account non-academic jobs (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/08/06/sociology-job-market-continues-recover-steadily). She notes that while these “applied” jobs often pay more than university teaching positions, graduates rarely know about them and professors may even discourage their students from entering these professions.

Unfortunately, the majority of Sociology grad students view the tenure-track job market as their only career choice, but there are many Sociologists who have chosen to work in applied settings. The skills gleaned through a Sociology degree are applicable – or dare I say, “marketable” – in a whole host of other venues, including government, corporations, and all sizes of nonprofits, local, state and national. We are researchers, lobbyists, program managers, teachers/trainers, and more.

![]()

I decided to organize a panel on this topic at the annual meeting of Sociologists for Women in Society, held in Washington, DC. And on February, 2015, three distinguished Applied Sociologists from the DC area presented about why they chose this route of practice, what they do and for which populations, and how they incorporate sociological principles into their work, framed by a race, class, gender lens. In this post, one of the speakers, Chantal Hailey, talks about her draw to applied work, which she began as a Sociology student at Howard University. After a number of years doing Applied Sociology, Chantal is now a first year doctoral student at New York University.

Mindy: What interested you in doing applied work?

Chantal: Throughout out my childhood, I lived, attended summer camps and had friends and family who lived in low-income urban neighborhoods. I was able to see how low-quality schools, subpar housing, limited opportunities and violence shaped young peoples’ lives and limited their potential. I had a passion to transform these communities into places where all people could thrive. But on the other hand, I was a nerd. I enjoyed research, history, math and statistics.

During my internship at a research branch of a community development corporation, I discovered that providing statistical trends on health, education, and housing to nonprofits could help them inform how they served low-income communities. I also discovered that the voices of women and people of color were sometimes absent from these discussions. I knew that in order to get a seat at the table, as a black woman, I needed to have the highest credential possible. So I began my academic journey at Howard University (as an) undergraduate in the Sociology department, knowing that my ultimate goal was to complete a doctoral degree in Sociology.

Mindy: Did you know you were learning about Applied Sociology at that point?

Chantal: While I was at Howard, I didn’t know of any distinction between applied and “pure” sociology. I just completed papers on topics that were important to me–public housing, poverty, and education. Urban Institute (UI) kept popping up in my literature reviews and I applied for internship there after my junior year.

Mindy: What did you do when you were at Urban Institute?

Chantal: At Urban Institute (UI), I transformed from an intern to a Research Assistant to a Research Associate. UI’s research is a combination of researcher-generated projects and responses to RFPs (Requests for Proposals). Two of my projects exemplify the type of applied sociology I was able to undertake at UI. The first is the “Long Term Outcomes for Chicago Public Housing Families” project (LTO). LTO is a 10-year longitudinal study of families whose Chicago public housing was demolished or revitalized through the Plan for Transformation. We employed mixed methodology – family surveys; in-depth interviews with heads of household, young adults and children; and administrative data review.

We found that after relocation from distressed public housing developments, families generally lived in better quality housing in safer neighborhoods, but many adults struggled with physical illnesses and youth suffered the consequences of chronic neighborhood violence.

Mindy: What was your role there? What did you do?

Chantal: As a team member in this project, I assisted in developing the survey, helped lead data analysis, generated the young adult interview guides and conducted in-depth interviews with the young people in the study. I also co-led and lead-authored research briefs on housing and neighborhood quality and youth. A research brief is a 15-20 page synopsis of research findings. Unlike most journal articles, there is not a long literature review.

This short article allows us to disseminate the findings to wide audiences. In addition to the standard research brief, we also produced blogs, HUD online journal articles, and radio reports; and briefed the Chicago Housing Authority, Senate committee members, and the press. LTO used sociological methods to understand policy, but intentionally shared this knowledge with wider policy makers and practitioners.

Mindy: You say that trained Sociologists have “indispensable tools” for applied sociology. Can you elaborate on this a bit?

Chantal: Sociology can address a plethora of subject areas that often intersect (i.e. inequality, education, crime and violence, health, etc.), and it unveils the mechanisms behind social problems. A Sociology education trains researchers to look for the hidden transcripts among social groups and interactions, not just the most apparent narrative. It allows for simultaneous macro, meso, and micro analysis to understand multiple contributing factors. And it emphasizes the impact social context has on policies’ implementation and outcomes.

This was especially apparent in the LTO study. We understood that in addition to families’ relocation from public housing, a series of key factors – including proliferating national rates of housing foreclosure, increasing Chicago neighborhood violence, and rising income inequality – also shaped families’ experiences in South Side Chicago neighborhoods.

A Sociology education provides an array of methodological tools that can be tailored to best address research questions (i.e. interviews, focus groups, ethnography, quantitative analysis). It pairs theories of race, class, family structure, etc. to better understand social issues. These analytic and research skills allow us to partner with government, non-profit, and academic agencies to both advance sociological theory and offer practical solutions to social problems.

Mindy: Thank you! And can you provide another example of applied work you’ve done, where you’ve been able to bring your analytic and research skills to the fore?

Chantal: In D.C., I participated in a Community Based Participatory Grant funded by NIH entitled Promoting Adolescent Sexual Safety (PASS). UI, University of California San Diego, D.C. Housing Authority, and D.C. public housing residents collaborated in the PASS project.

This research team – along with a mix of individuals from different racial, class, and professional backgrounds – aimed to develop a program to increase sexual health and decrease sexual violence.

Mindy: How did you use what you were learning as a Sociology student/practitioner?

Chantal: Again, we used sociological methods to conduct this project, including an adult and youth survey, in-depth interviews with community members, participant observations, and focus groups.

Mindy: You said this project was participatory. Can you talk about who was involved? How was it participatory?

Chantal: Through the grant, we developed a community advisory board, a group of 15 residents who participated in creating the PASS program. The interactions between the community advisory board, community practitioners, and the researchers challenged the researchers to not only study educational, class, geographic and racial inequalities, but also to assess how our interactions dismantled or exacerbated power inequities.

Mindy: Earlier, when we spoke, you talked about what it was like to be an African-American researcher who also had a personal understanding of the experience of people you were researching. Can you talk a little about that?

Chantal: As an African American woman on the project with family who lived in D.C., I was personally challenged to both create distance as a researcher and closeness as a fellow black D.C. resident. I often found myself “code-switching” during community meetings, as I communicated with both my co-workers and the community members. Feeling a responsibility to and, often, sympathizing with the desires of the researchers and the residents, I also had to sometimes explain and mediate diverging understandings during conflicts. This closeness and distance dichotomy was also pertinent during data analysis. While my experiences allowed me to recognize and interpret focus group participants’ terminologies and cultural cues, I had to ensure that my sympathies with the community did not cloud my ability to see inconvenient truths.

Mindy: And how did you get what you learned out there to your target audiences?

Chantal: This research project, like most UI projects, focused on dissemination to wider audiences in palatable formats–a community data walk, research briefs, blogs and journal articles.

Mindy: Finally…now you’re a doctoral student at NYU and studying Sociology. How do you see yourself moving forward as a Sociologist? How will you incorporate what you’ve learned into your future practice? (or is that something you’re still figuring out!)

Chantal: As I continue in graduate school at NYU, I aim to crystalize my research identity and trajectory. I have methodological and policy research experience through the Urban Institute, and I am gaining theoretical expertise while completing my doctoral degree. I hope to incorporate these elements into my research and become a conduit between academia, policy makers, and urban communities to make inner city neighborhoods a place where all children can thrive. A mentor once advised me that graduate school is a journey where you begin in one place and end in another. I am tooled with amazing applied experiences and I’m excited to see how my graduate school journey directs my path.

by Mindy Fried | Mar 25, 2015 | applied sociology, gender, program evaluation, race, selecting evaluation researcher, social class, social justice, social science research, working with evaluation researcher

![]()

After working in the policy world in Massachusetts for many years, going back to graduate school in Sociology felt like going to a candy store in the country* every day, where I could read interesting books, have stimulating conversations, learn how to do research, and then write about it. I admired my professors, and I was kind of amazed that their job was to take me seriously and support my development as a scholar. Later, while I was working on my dissertation, I got a job teaching part-time in a local university while a full-time professor went out on leave. It was challenging; it was fun; and it was an incredible opportunity to experiment with pedagogy. I learned that I loved teaching, and over the next two years, got hired to teach a wide range of sociology classes – about families, sex and gender, feminism, work, and women and leadership – at several other Boston universities.

![]()

But the more I learned about the full-time tenure-track teaching world, the more I realized it was just not my thing. First off, I couldn’t imagine “starting over” again at the bottom of the career ladder, with what could be six grueling years of slogging towards tenure. Nor could I imagine the idea of a job for life – the promise of tenure – working with the same folks for the next few decades (apologies to my mythical could-have-been colleagues!). Call me fickle, but I enjoyed changing jobs every few years, having new and varied challenges, and working with a diverse array of people.

Learning on the job

By luck, while I was taking research methods classes, I was offered a small consulting job to evaluate the impact of a well-established training program on its activist participants. Here was an opportunity to put my newfound knowledge to use. Except that no one was teaching how to evaluate social programs in sociology graduate programs! I did have some experience with “program evaluation”. When I was directing a statewide child care project that was federally funded, some guy was hired by the state to evaluate my program. He met with me once at the beginning of the project, and at the end, he wrote a glowing report.

![]()

Every so often, I wondered if he’d be back. In the end, he really had no basis upon which to evaluate the strengths and challenges the project was facing – and believe me, there were plenty. But I wasn’t going to complain if he was phoning it in!

Since I had no idea how to evaluate a program, I hired someone who did, and for the next few years, she trained me and my sociologist friend, Claire, in how to use research skills to evaluate social programs. I never intended to continue doing this “applied” work for the next 20 years, but that is essentially what has happened. When I first started, I wasn’t very good at it, and I thought it was boring. But a couple decades later, I have learned a whole lot about how to do it well, and (luckily) find this work fascinating.

Making a choice to be an applied sociologist

The choice to be an “applied sociologist” is not a rejection or devaluation of academic sociology. It is a choice that is, in part, a function of economic imperatives – a tight job market, especially if you don’t want to move – but also a choice to make a different kind of difference. To impact the social world through organizations that are impacting people: through service, through organizing, and through education and advocacy, in the areas of public health, education, urban planning, climate change, arts and arts education and many more.

I have learned that it makes me happy to use the research and writing skills I learned in graduate school as a tool to help promote social change, through the vehicle of strengthening nonprofit organizations and improving philanthropic decision-making. Once considered the stepchild of the field, applied sociology is now gaining prominence, but largely because the economy has not produced the plethora of academic sociology jobs once predicted.

“Close to a perfect match”

In a 2013 article in Inside Higher Ed, Roberta Spalter-Roth, from the American Sociological Association, commented that “In sociology, there is close to a perfect match between available jobs and new Ph.D.s” (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/08/06/sociology-job-market-continues-recover-steadily). But this is only if you factor in the many government, nonprofit and research analyst jobs out there that require the skills and sociological perspectives learned in graduate school. Spalter-Roth notes that these jobs often pay more than university teaching positions, but graduates rarely know about them and professors may even discourage their students from entering these professions.

This year, my applied sociology friends and I agree that the “applied route” seems to be gaining some traction, with increased interest from universities and professional associations. A number of us have been on a (minor) speaking circuit, talking to graduate students at the request of sociology departments about choosing applied sociology as a career. And this year, the Sociology Department of a major research university, Boston College, hired me to teach a course on Evaluation Research. (Kudos to BC Sociology for recognizing the importance of this avenue for sociologists-in-training!)

Panel at Sociologists for Women in Society: Choosing Applied Sociology (sponsored by the Career Development Committee)

Given this increased interest, and what I believe is a need for sociologists to promote the health and well-being of organizations and communities using research and sociological principles, I organized a panel on this topic at an annual meeting of my favorite national feminist sociology organization, Sociologists for Women in Society.

The panel included three distinguished applied sociologists from the DC area, where the meeting was held, who presented about why they chose this route of practice, what they do and for what populations, and how they incorporate sociological principles into their work, framed by a race, class, gender lens.

The speakers, all based in DC, included Tekisha Everette, a lobbyist for the American Diabetes Association; Andrea Robles, a research analyst at the Corporation for National and Community Service; and Chantal Hailey, who ran evaluation projects at the national Urban Institute and elsewhere, and is currently a sociology doctoral student at NYU. One other panelist, Rita Stephens, was not able to make it because of a blasted snowstorm, but she would have rounded out the panel very nicely as she works at the State Department. The three women spoke to a standing and sitting room only crowd at the meeting, followed by numerous informal conversations, attesting to the fact that there is a hunger for this kind of work.

In my next couple of blog posts, I will allow these amazing women’s words speak for themselves. I hope that their words stimulate a dialogue about the value of and choice to pursue sociology outside of the academy. Based on the remarkable response at this meeting and in classrooms where I talk about applied sociology, my sense is that sociologists want to know about alternatives to working within academia. The words of these speakers inspired me and I hope they inspire you.

“I was interested in doing applied work that could lead to positive social

change. Somehow, it seemed like I wanted to be part of making the world

a better place.”

Sociologist, Andrea Robles

Corporation for National and Community Service

Check out this excellent blog post by Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, Research and Social Media Consultant with Social Science Insights in Australia, called What is Applied Sociology?, published in Sociology at Work: Working for Social Change: http://sociologyatwork.org/about/what-is-applied-sociology/

*Brandeis University, which is actually in the suburb of Waltham, Massachusetts, but looked like the country to this city girl!

by Mindy Fried | May 2, 2014 | child care, early education and care, fathering, fathers, feminist, gender, Joe Ehrmann, making choices, mothers, New York Mets, parental leave policy, pro-feminist, Riverside High School, value of caregiving work

![]()

I was a high school cheerleader. Whew – I’ve gotten the confessional part of this post out of the way. In all honesty, I hated football, and didn’t know anything about the game. I had discovered ballet and modern dance at age seven, and very soon was taking lessons four times a week. Dance was my life. This was an era when girls were often discouraged or excluded from playing sports, before the passage of Title IX. When I reached Riverside High School (RHS) in Buffalo, New York, the only dance-like option available for athletic girls was cheerleading. So another dancer friend and I plunged into the world of rah-rah, feeling like outsiders even though we were viewed as football-loving cheerleaders. Perhaps more importantly, we were also considered “popular girls”, with status that was derived from our official role in supporting the football players, “our men”, who represented the epitome of masculinity.

![]()

Like most occupations that are female-dominated, our all-female cheerleading team was a vehicle through which we were able to bond. Our coach was the first lesbian I ever met, closeted of course in those days, who supported us in our prominent role, despite the fact that it was a gendered role. Our job was quite simple. We were to rev up the audience so that they could rev up the players. We cheerleaders – dressed in our short skirts and lettered sweaters – were happy to cheer and leap with chronically fixed smiles, as we performed to an appreciative crowd. Although unlike me, most of my “sisters” really meant it when they cheered for the players. Here was one of our popular chants, which I loved not because of the words, which glorified the heroes of the game, but because of the athletic moves that accompanied them:

“They always call him Mr. Touchdown

They always call him Mr. T.

He can run and and kick and throw

Give him the ball and just look at him go

Hip, hip, hooray for Mister Touch-down

He’s gonna beat ‘em today

So give a great big cheer (WOO! – cheers the crowd ) for the hero of the year,

Mister Touchdown, RHS (Riverside High School)”

![]()

The real hero of the RHS team was Joe Ehrmann, a star football player with a solid frame, wide, powerful neck, and muscles that popped out of his uniform. Unlike most other girls in school, I was not interested in football players, including Joe. I presumed – right or wrong – that if you were a football player, you probably had an inflated ego and you were short on smarts.

That said, it was clear that Joe was different than the other ball players. He was funny and clever, and a “mensch” – aka a really sweet guy. I remember his performance in an all-school “assembly” when Joe got up in front of the whole school and danced in a hula skirt. At the time, this was hysterical and unheard of – a popular football player cross-dressing for laughs. He wasn’t afraid to be outrageous, and perhaps understood that a hulk of a man displaying so-called femininity was discordant and therefore, funny.

No surprise that Joe and I didn’t see each other after high school, but we both attended Syracuse University. He went on to become a star player on SU’s football team, and I went on to become an anti-war activist and aspiring feminist. When Joe graduated from SU, he was immediately drafted to play defensive tackle in the NFL for the Baltimore Colts. Given my disconnect from the world of football – in my mind, a violent sport that typifies our “masculinist” culture – I knew nothing about Joe and his success over the next four decades. That is, until I began to teach courses on gender and workplace issues, and lo and behold, I discovered that Joe and I had a lot in common. Over the years, Joe had become a minister and popular motivational speaker who chose sports as his bully pulpit to preach all over the country about the damaging social construct of what it means “to be a man”.

In his blog, Joe writes about 10 lessons he’s learning about sports in America. Lesson # 7 says:

At the core of much of America’s social chaos – from boys with guns, to girls with babies, immorality in board rooms and the beat down women take– is the socialization of boys into men. Violence, a sense of superiority over women, and emotional disconnectedness are not inherent to masculinity – they are the results of societal messages that define and dictate American masculinity.

Speaking like a feminist sociologist, Joe says that “America is increasingly becoming a toxic environment for the development of boys into men”…which “disconnects a boy’s heart from his head (and) contributes to a culture of violence, emotional invulnerability, toughness and stoicism (that) perpetuates the challenge of helping boys become loving, contributing and productive citizens”.

![]()

I wouldn’t have found Joe, had I not become aware of a controversy around a couple of macho sportscasters who run a morning radio show on WFAN in New York City, called Boomer and Carton, followed by a social critique from my old classmate, Joe. The “Boomer and Carton” show began with Carton ranting about a New York Mets player, Daniel Murphy, who took two days of paternity leave, or as they called it a two-game paternity leave, to be with his wife as she was birthing their baby. He said that he could understand why a man would be with his wife while she’s HAVING the baby,

But to ME, and this is MY sensibility – Assuming the birth went well; assuming your wife is fine; assuming the baby is fine – (then he should take off) 24 hours! Baby’s good; you stay there; you have a good support system for the mom and the baby. (Then) you get your ass back to the team and you play baseball! That’s my take on it.

![]()

As Carton finishes these last words, he knocks his fist on the table, agitated, and then continues: “What do you need to do anyway? You’re not breastfeeding the kid!…I got four of these little rug rats! There’s nothing to do!”

Initially, Boomer counters by saying that Daniel Murphy has the legal right to be with the mom and his newborn, but when pressed by his co-host, Carton, about what HE would have done, Boomer backs off and says:

Quite frankly I would’ve said (to my wife), C-section before the season starts. I need to be at opening day. I’m sorry, this is what makes our money. This is how we’re going to live our life. This is going to give my child every opportunity to be a success in life. I’ll be able to afford any college I want to send my kid to because I’m a baseball player.

So here we have two sportscasters telling us that a) “real” men have no responsibility, nor should they have an interest in being an involved father; and b) “real” men should tell their wives that this is how it’s going to be: You wrap your birthing around my work schedule, and then when you’re done popping out the baby, I’m outa’ here because I’m making money to send this kid to college, and that’s more important.

This is where former NFL player Joe Ehrmann chimed in.

I think these comments are pretty shortsighted and reflect old school thinking about masculinity and fatherhood. Paternity leave is critical in helping dads create life-long bonding and sharing in the responsibilities of raising emotionally healthy children. To miss the life altering experience of ‘co-laboring’ in a delivery room due to nonessential work-related responsibilities is to create false values.

Take that, Boomer and Carton!

![]()

In the background throughout all this hub-bub was Daniel Murphy who, without any fanfare, commented that he did hear about the controversy around his leave-taking, but he didn’t care. “That’s the awesome part about being blessed, about being a parent, is you get that choice. My wife and I discussed it, and we felt the best thing for our family was for me to try to stay for an extra day – that being Wednesday, due to the fact that she can’t travel for two weeks”.

Instead of cow-towing to the traditional view that men – in particular, high-priced athletes – should put work over family, Murphy exhibited compassion for his wife and a desire to be an involved dad. “It’s going to be tough for her to get up to New York for a month. I can only speak from my experience – a father seeing his wife – she was completely finished. I mean, she was done. She had surgery and she was wiped. Having me there helped a lot, and vice versa, to take some of the load off. … It felt, for us, like the right decision to make.”

Okay, Murphy defended his right to take a measly two days off from work. This isn’t so different from thousands of men around the nation, as the range of men’s use of parental leave goes somewhere from a couple days to a couple of weeks. And that time is generally taken as vacation time, which disassociates it from the act of involved fathering. But still, the public face of this story elevates the importance of father involvement in child caring and co-parenting, with Murphy as the protagonist, and my old classmate, Joe, the advocate who understands and has a lot of important things to say about it.

![]()

Joe continues to give inspirational talks around the country, where he questions how men begin to understand themselves and connect more deeply to others. “It’s a long term process but it starts with the idea that you can’t keep hiding and protecting yourself. You’ve got to be able to let people in. Then you have a chance to be truly loved and to love.”

Check out Joe Ehrmann’s TedX Baltimore talk called “Be a Man”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jVI1Xutc_Ws

by Mindy Fried | Apr 20, 2014 | aging, connections with people, engaged aging, family, gender, making choices, retirement, social science research, women and work

re•tire [ri-tahyuh r]

1. to withdraw, or go away or apart, to a place of privacy, shelter, or seclusion: “He retired to his study”.

2. to fall back or retreat in an orderly fashion and according to plan, as from battle, an untenable position, danger, etc.

3. to withdraw or remove oneself: “After announcing the guests, the butler retired”.

4. to withdraw from office, business, or active life, usually because of age: to retire at the age of sixty.

5. retirement or withdrawal, as from worldly matters or the company of others.

One of my friends is passionate about Latin America and travels widely, monitoring elections and writing for an international journal. Her life-long “career” as an energy consultant is gradually shifting to her passionate “avocation”.

A family member who is a therapist decided to significantly pull back on her work hours, but then it didn’t “feel right”. Instead of leaving her practice, she decided to slow down the process, and continues to see clients. She is working fewer hours, spends more time with her children and grandchildren, and has increased her volunteer work.

Another friend had a decades-long successful career as a librarian. As her retirement approached, she was uncertain about what would come next, but stayed open to possibilities. She now works as a volunteer in a number of non-profit organizations, travels, reads, and has time to hang out with friends and former colleagues.

And me? I don’t plan to retire for a long time. First off, even though I’m technically approaching the typical “retirement age”, I like to work because I’d like to think that I’m contributing to making the world a slightly better place, at least in the small piece of the universe I inhabit. Maybe more basic is the fact that, like many people, I can’t afford to retire!

When it comes to major life changes, I like to be fully informed, so I decided to study “retirement narratives”. It’s an informal study that is personally driven by my desire to remain engaged in and satisfied with life when I stop working for pay someday (who knows which day). My study is a pre-emptive strike against loneliness and a concern that as I age, I will be on the periphery, no longer a contributor to the world, no longer a player in daily life…I know this can happen because I’ve seen it happen, and I bet you have too. My observations and intuition have been confirmed by reading a ton of books about aging, in preparation for an aging course I taught at Brandeis University, as well as following the substantial media coverage of issues of aging. My feeling was that my informal study would provide me with an opportunity to better understand this life changing event from a sociological perspective.

My role model for retirement was my father, who didn’t stop working in his job as an English professor until he was around 95 years old. I used to think that his formula – essentially, to never stop working – was how I wanted to live my life. I, too, imagined that I would basically work full-time until I dropped. But now I’m re-thinking my plans. And that’s where my research comes in. My study basically consists of informal “interviews” with friends who are reducing their paid work hours, as well as informal “chats” with acquaintances I run into in random places, like CVS, walking around Jamaica Pond, and on the street. For the people I know and with whom I have regular contact, I plan to follow them over a long period of time, meaning that I want to see what they do and how they adjust for as long as I know them, which could be until I or they die. With these friends, I hear the intimate details of their decision-making. Some of them had full-time jobs in organizations or institutions that provide incentives to retire, and some worried that they might lose their jobs past a certain age. Others work more autonomously as therapists or consultants.

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?

The research questions I employ with my “almost, kinda” friends have a one-two punch. We start by asking one another a few basic questions: “How are you?”, is the starter. Can’t get more basic than that! And then a probing question: “And what have you been up to?” Now this question also seems pretty basic but the reply reveals a lot through their words as well as their body language. If/when they say they’re retired – or just that they left their job of many years – my panoply of probes is unleashed and I ask, “Is it a good thing?” This is a general yes-no question, followed up by “How do you fill your days?” That’s the meat of what I’m looking for.

My informal study has no real parameters. My “sample” is fairly random; it’s not designed with any demographic in mind; I’ll talk to anyone. I’m not keeping track of how many people I’m interviewing, and I’m cool with going with the flow of the conversation, wherever it leads. I’m not discovering anything new, in a broader sense. There’s plenty of literature that argues for continued engagement in life, as one ages. Instead, my study is about getting at the particulars. What do people do as they’re considering retirement? Do they consciously prepare? Once they retire, what are they doing and how do they feel about it?

The issue of retirement has become even more salient because we are living longer. For example, in 2000, the life expectancy in the U.S. for women was 77.6, and for men it was 74.3. In 2010, those numbers had jumped to 79 and 76 respectively. It’s important to note that there is also a racial disparity, as reflected in 2010 figures, with white women projected to live until they are 81.3, and African-American women projected to live until they are 78. For men, the comparison between white and African-American men is 76.5 to 71.8, respectively.

Despite these gender and race disparities, an increase in longevity has resulted in a larger gap in time between official retirement and the point where people stop working for pay altogether. Dr. Mo Wang from the University of Maryland calls this period “post-retirement”, a time when people may choose self-employment, part-time work or temporary jobs. Dr. Jacquelyn B. James, from Boston College’s Sloan Center on Aging and Work (http://www.bc.edu/research/agingandwork/) calls this “transition” period “the “crown of life”, which implies that it is a special time, perhaps less fraught with the demands of one’s “regular” job which may have consumed years or decades of their lives. According to Wang’s research, “retirees who transition from full-time work into a temporary or part-time job experience fewer major diseases and are able to function better day-to-day than people who stop working altogether.”

At the same time, other research doesn’t focus on the impact of paid work; rather, it notes that as people age, those who stay engaged in life, both socially and intellectually, will fare much better than those who retreat, regardless if they are working for pay or doing something else like volunteering, doing unpaid caregiving work, or just about any activity that engages them.

In my effort to amass retirement narratives, I welcome you to tell me yours! It would be great to hear about your journey, whether you’re in the thinking stage or you have started instituting changes in your paid work schedule, or you have left a paid job and are in a next chapter of your life!

Also, just for fun, check out this video of a policy debate between Republican Paul Ryan who wants to increase the retirement age, claiming that the Social Security fund is depleted, and Democrat Debbie Wasserman Schultz, who strongly disagrees: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIrltAkTf38

by Mindy Fried | Feb 12, 2013 | conservatives, ethnicity, G.O.P., gender, health, health care, inequality, progressive policies, race, Republicans, social class, social policy, social science research

The American Enterprise Institute just published a speech by G.O.P. darling and House Majority Leader, Eric Cantor, in which he calls for cutting all federal funds for social science research, insisting that the money would be better spent finding cures to diseases. He uses the story of a child named Katie who battled cancer, and who “just happened” to be sitting in the front row of his audience. “Katie became a part of my congressional office’s family and even interned with us”, he is quoted as saying. “We rooted for her, and prayed for her. Today, she is a bright 12-year-old that is making her own life work despite ongoing challenges…Katie, thank you for being here with us”.

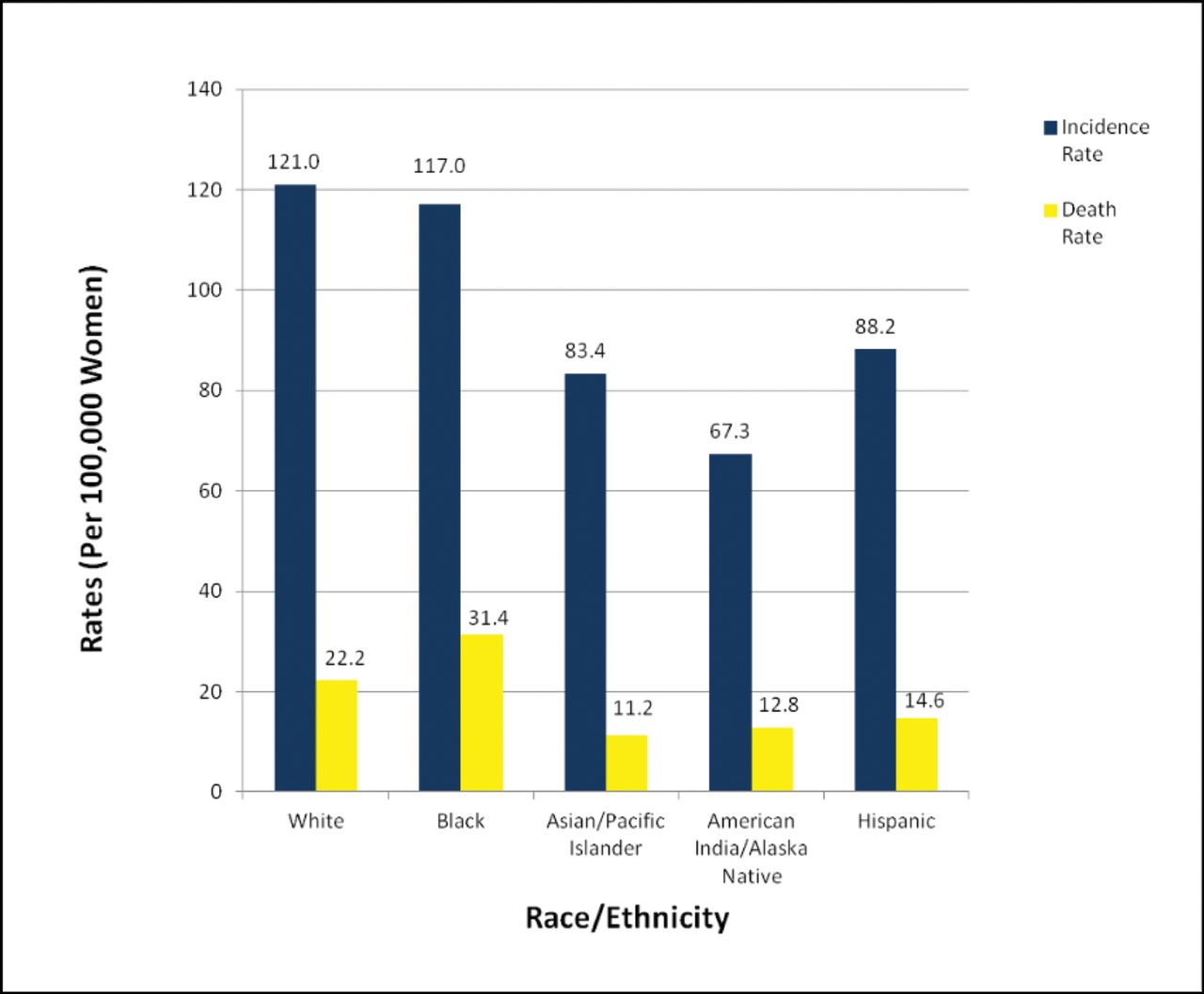

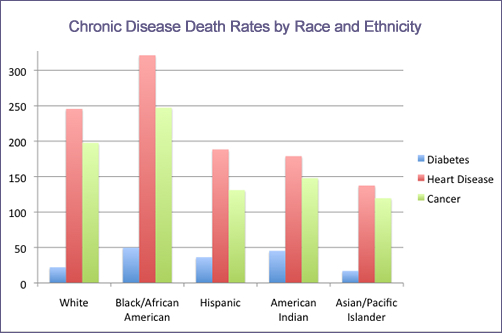

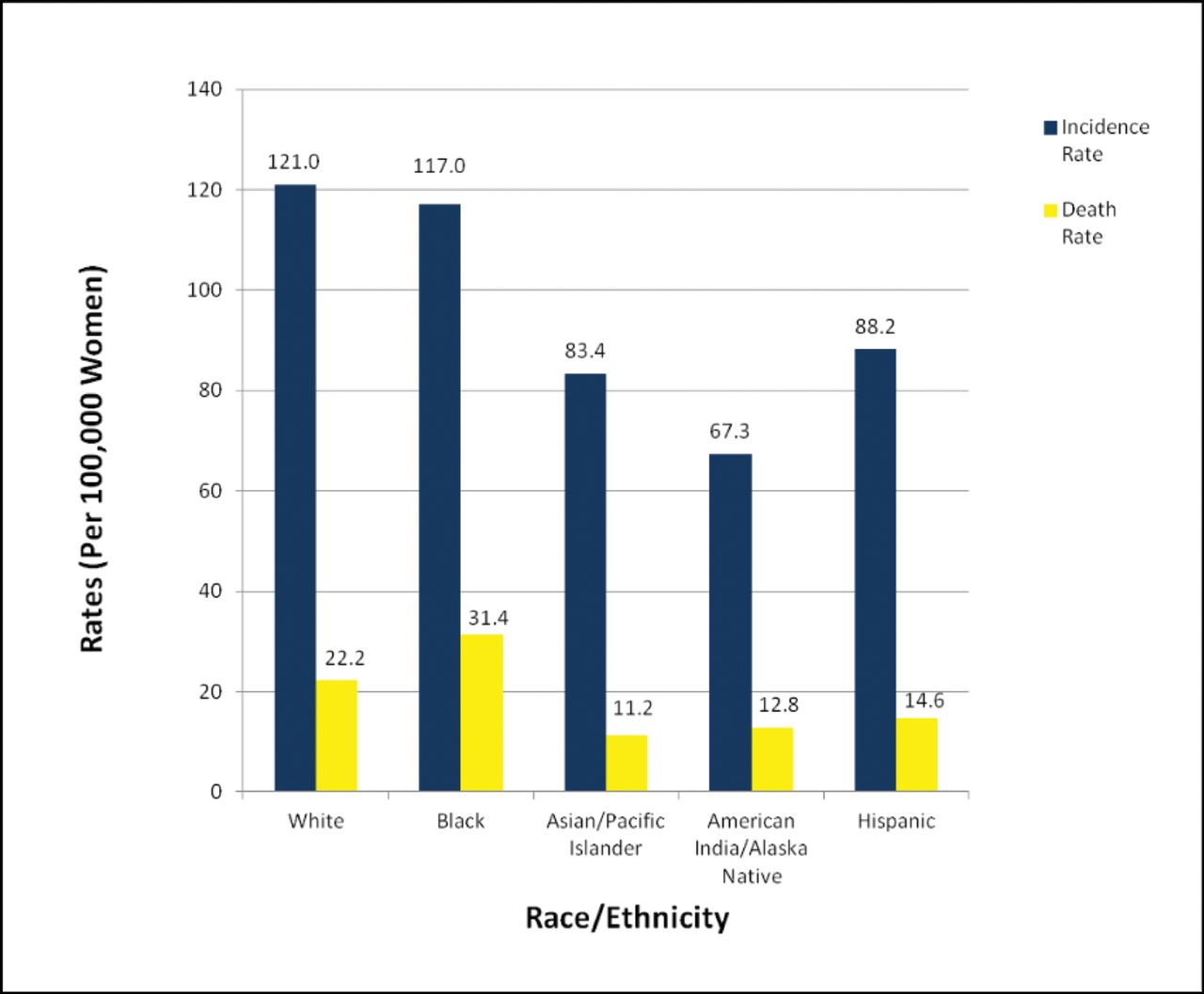

(Please note that the graphic visualizations in this post illustrate the importance of information generated through social science research which have critical implications for policy, e.g., the disproportionate impact of poverty on health outcomes by race/ethnicity) .

I can imagine the emotions in that room, as the audience learns that Katie’s disease is now in remission. Some people of faith in the crowd might be thinking that prayers led to the improvement in her health. But Cantor does not invoke divine intervention. Nor does he totally discount the role that publicly funded resources may have played in helping restore Katie’s health. On the contrary, he cannily declares that there is “an appropriate and necessary role for the federal government to ensure funding for basic medical research. Doing all we can to facilitate medical breakthroughs for people like Katie should be a priority. We can and must do better”.

But investing more public funds in research on medical cures, says Cantor, would require cuts in funding for social science research. Presumably, his argument is in the interests of budgetary discipline, because it makes no sense if the goal is to improve people’s health. Less social science research dollars will only weaken our capacity to understand the critical link between the social determinants of disease and health outcomes. We need to ask: Why did Katie get sick? Was she living near a power plant or did she go to a “sick school”? What kinds of services did she have access to? What is Katie’s ethnic/racial background? What is her class background? Because chances are, if Katie is white and middle-class, her access to services are better than if she’s black or Latino and poor.

Cantor trots out the familiar conservative template: We need policies that are based on “self-reliance, faith in the individual, trust in the family and accountability in government”. He declares that the House Majority – aka Republicans – “will pursue an agenda based on a shared vision of creating the conditions for health, happiness, and prosperity for more Americans and their families. And to restrain Washington from interfering in those pursuits”.

But while Cantor frames this as a message of empowerment, his solutions will only reproduce and expand poverty and inequality. Self-reliance is code for slashing government funding. Restraining Washington from interfering with health and prosperity will mean reducing taxes for the rich. And cutting social science research will eliminate needed publicly-funded analyses that provide an essential critique of social and economic policies and their impact.

Cantor’s stance is calculated to appeal to people who are struggling in a tough economy. In his speech, he argues that in America, where two bicycle mechanics, the Wright Brothers, “gave mankind the gift of flight”, we have the power to overcome adversity. “That’s who we are”, he says. Moreover, he argues that throughout history, “children were largely consigned to the same station in life as their parents. But not here. In America, the son of a shoe salesman can grow up to be president. In America, the daughter of a poor single mother can grow up to own her own television network. In America, the grandson of poor immigrants who fled religious persecution in Russia can become the majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives”.

All I can say is, sign me up, Eric! I’m the grand-daughter of a Russian immigrant, and maybe I’d like to become the majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives! Honestly? I get weary when I hear about the American dream from another rich, white guy who points to exceptions to the rule, and cynically tries to generalize them.

I just came back from a four-day feminist sociology meeting, sponsored by the organization, Sociologists for Women in Society (SWS) http://www.socwomen.org/web/, in which 250 scholars from around the U.S. and beyond, shared their research about how gender, race and class affect power and status, and how these determinants affect the realities of people’s lives – including their access to quality health care, decent jobs with benefits, high quality education, freedom from discrimination, and safe environments. These are the conditions that Cantor claims should be the right of all Americans, and yet his agenda makes them all less achievable. If Eric Cantor had been at that conference for just one hour, he would have heard about the importance of social science research in understanding systems that reproduce disadvantage for low-income people, immigrants, people of color, same-sex couples and more… But maybe if you preach self-reliance, limited government involvement, and the power of prayer, even a group of brilliant social scientists won’t change your mind.