by Mindy Fried | Mar 12, 2013 | arts, arts education, AWP conference, creative writing, loss, sociological imagination, women and work, women artists

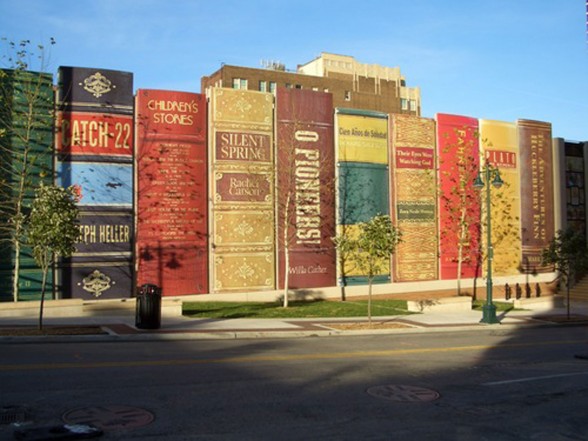

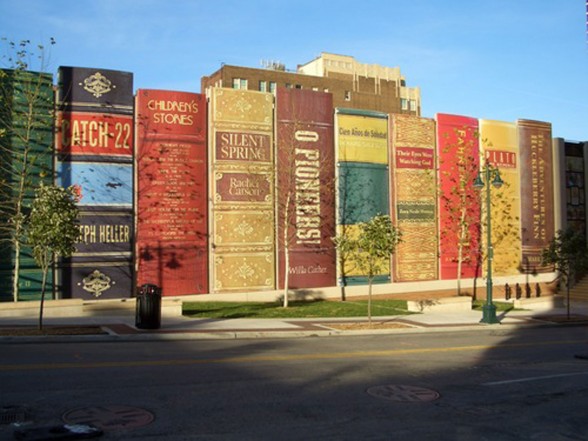

Writing is a solo act, but for those in attendance at the conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, or AWP (https://www.awpwriter.org/) this past weekend, you’d think it was one big party, with over 12,000 people moving through the sterile hallways of Boston’s massive Hynes Convention Center to attend hundreds of sessions. I had been forewarned that this event was downright overwhelming. So before I stepped foot into the Hynes, I carefully studied the program, selected sessions that fit my criteria, and found out exactly where they were physically located. Getting lost in the Convention Center was not on my agenda! As it turned out, this surgical approach served me well.

In one day, I managed to attend five sessions, chat with five random strangers, purchase an energy bar for nearly $5, and wander around the book fair where I was invited by at least five non-residency writing programs to look at their literature. I spoke with five or so small presses about their books, and was also accosted by a woman selling a weeklong “writing trip” to Paris, which was, in sum, a total rip-off. Of my small sample of informal interviewees, a few were undergraduate creative writing majors who were totally blown away by the panoply of rich resources in one place; one was an art history professor and another was a writing professor.

But I wasn’t there to make friends, although later I joined the Women’s Caucus of the organization (yes, there is gender bias everywhere!). I was there because I’m writing a memoir about the experience of caring for my dad in his final year of life, in which I am inter-weaving my family’s experience of political persecution, the FBI and more. I wanted to hear published authors talk about their experience writing memoirs, and to garner some tips about the process of publishing this type of book.

Here are a few gems that I got from the conference:

In a panel called “The Art of Losing”, authors talked about how profound personal loss fuels their writing. One of my favorite speakers on this panel was Jennine Capó Cruce, author of How to Leave Hialeah (http://www.jcapocrucet.com/), who said that she was told that she shouldn’t write from anger. But as she wrote her book, she saw rage as her source, and while writing her book, recognized that underneath her rage was grief.

In a panel called “How Do You Know You’re Ready?”, novelists shared stories about manuscripts they either sent to agents too soon or had locked in drawers, never to see the light of day. I realized that the question of when a book is complete is a universal question. The panelists seemed to agree that knowing when you’re done writing a book is a “visceral thing”. I was touched that the panelists also welcomed attendees to approach them with questions at the end of the session. I asked novelist Dawn Tripp (http://www.dawntripp.com/) for suggestions about making a “pitch” to an agent. She offered me a few tips, including “make it short and to the point”. And another panelist, Kim Wright, author of Love in Mid-Air (http://loveinmidair.com/), added that it’s important to maintain the voice of the book when you’re trying to get others interested.

In a session called “Memoir Beyond the Self”, panelists talked about the importance of writing from one’s personal experience and broadening it to reflect on cultural implications. Travel writer and journalist, Colleen Kinder (http://www.colleenkinder.com/Colleenkinder/home.html) said, “personal essays have to be brave”, and she talked about the importance of “braiding” and “weaving” different strands of a story together. In describing this braiding and weaving process, Leslie Jamison, author of Empathy Exams (http://www.graywolfpress.org/Latest_News/Latest_News/Leslie_Jamison_wins_Graywolf_Press_Nonfiction_Prize//) said that “something in one sphere poses a question that another sphere can answer”. That intrigued me.

In a session called, “It’s Complicated: Memoir-Writing in the Political Sphere”, Melissa Febos talked about her book, Whip Smart, in which she wrote about her three years as a dominatrix while attending a liberal arts college in New York City (http://melissafebos.com/). Kassi Underwood talked about her book, A Lost Child, but Not Mine (http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/fashion/a-lost-child-but-not-mine-modern-love.html?pagewanted=all), which chronicles her experience of having an abortion and then encountering her ex-boyfriend who was now a father. And Nick Flynn described the writing of his book, Another Night in Suck City about seeing his estranged father in the homeless shelter where he worked. The book was later turned into a film called, “Being Flynn” with Robert DeNiro and Julianne Moore. Talk about star struck!

In a session called “Poetics of Fiction in/at Buffalo”, three writers read from their work about my poverty-stricken, yet vibrant hometown of Buffalo, New York. Ted Pelton (http://www.starcherone.com/ted/) began with this poem: “Buffalo Buffalo, Buffalo Buffalo Buffalo…”, saying that no other city can be a noun, verb and adjective. And Buffalo writer of Buffalo Noir, Dmitri Anastasopoulos (http://www.akashicbooks.com/catalog-tag/dimitri-anastasopoulos/), brought the experience full circle for me, when he said, “Buffalo is all about loss”.

The conference had a commercial element as well: In a so-called “Book Fair”, the small presses are there to entice writers, as are the creative writing programs and artists’ retreats. But one of my favorite booths in the exhibition hall was run by 826 National, a nonprofit organization that runs eight writing and tutoring centers around the country, aimed at helping at-risk youth find a voice to tell their stories (http://www.826national.org/). And who knows? Perhaps these young people will be the authors of tomorrow, and future attendees of this chaotic but enriching experience that is AWP…

by Mindy Fried | Jan 23, 2012 | aging, Blue Zones, engaged aging, family, House Un-American Activities Committee, HUAC, immigrants, loss, resiliency

The great thing about getting older is that you don’t lose all the other ages you’ve been.

Madeleine L’Engle

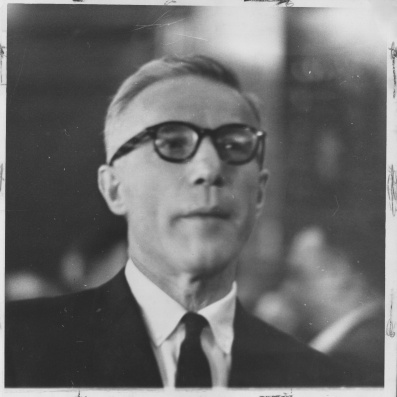

It is nearly one year ago that my father passed away. On that day, the headline of the Buffalo News proclaimed, “He was a man with a purpose”, with a smaller headline saying “Manny Fried, a guiding presence to area’s actors, writers and social activists, dies at 97.”

Anyone who observed my father as he surpassed the 80-year-old mark, then the 90-year-old mark, and eventually the 97-year-old mark wondered what kept him “so young”. At age 80, he was still jogging. At 90, he was still acting, writing and going to political meetings. And at 95, he performed a one-man autobiographical show, sitting on stage at a reputable Buffalo, New York theater, telling stories about his life with passion and vigor, for over a month of weekend performances. As heirs to 50% of our father’s genes, my sister and I hope that we can only be so lucky! The other side of the family is gifted with tons of creativity, but unfortunately rifled with bi-polar disease and plenty of medical problems. The former we welcome; the latter, we rationalize were the result of poor “lifestyle choices”.

What is it that keeps people ticking for a long time? My father claimed it was a function of good genes from his hearty immigrant parents who lived until they were nearly 100. That, coupled with eating judiciously (he had a sign on his fridge that said “EAT LESS”!), consistent exercise, and staying involved intellectually… He had a rough life trajectory, but developed a resilience he absorbed from his father, who told him, “When you fall down, you get up.” In the 1940s and ’50s, as a labor organizer for the radical Electrical Workers union, he was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Rather than “taking the 5th”, and saying that he refused to speak on the grounds that anything he said could be used against him, he refused to respond to the Committee’s questions, challenging the right of the Committee to exist. He was unable to find work in the U.S., and ultimately worked for a Canadian company, and also wrote plays about his life experience.

As I move closer to what we define as “young old age” in our society, I am recognizing the elements of my father’s life that continued to fuel his sense of purpose. In fact, just about everything he did mirrors much of the research on aging and longevity as a combination of genetics and lifestyle choices. According to some twin studies, around 20-30% of an individual’s lifespan is related to genes, and the rest is due to individual behaviors and environmental factors which can be modified. Other studies demonstrate that some people have fewer choices than others, particularly given the greater environmental pollution in poorer neighborhoods, and differential access to quality health care for poor people and people of color.

Dan Buettner, in his Blue Zone project, traveled around the world looking for key areas that foster centenarians, people who lived to be 100 or more. He wanted to know what factors contributed to a long life.

Beuttner and his team spent seven years studying four “Blue Zones” where they met people who were aging in an extraordinary way. They interviewed dozens of centenarians, worked with local medical experts, and studied local cultures and lifestyles. Buettner said that each Blue Zone revealed its own recipe for longevity, but many of the fundamental ingredients were the same. Ultimately, he identified nine common lessons of living longer, which he felt were deeply embedded in the cultures they studied.

He found that the Italian island of Sardinia has the highest number of male centenarians in the world; Okinawa, Japan has the longest disability-free life expectancy; and in Loma Linda, Calif., a community of Seventh Day Adventists has a life expectancy that’s around ten years more than that of other Americans. What contributes to these long-living elders? Buettner says that first off, they eat a healthy diet and they get “natural” exercise, where physical activity – like walking around the community or climbing up and down hills – is a natural part of their daily lives.

They remain socially engaged in their communities, whether it be in a village or with a group of strong friends and family in which they are valued. And these centenarians continue to find meaning or purpose in their lives. Buettner describes 104-year-old Giovanni Sannai of Sardinia, saying,

“He was out chopping wood at 9 in the morning…He started his day with a glass of wine and there was a steady parade of people coming by to ask his advice. That’s one of the characteristics of the Sardinian Blue Zone — the older you get, the more celebrated you are.”

For those of us who don’t live on an island, or in a culture that reveres old age, how will we shape our lives moving forward, to maximize healthy aging? It is not “natural” for older people to disengage with their lives; in fact, contemporary aging research provides evidence of the importance of being involved in activities that inspire interest or passion, whether it be with one’s family and friends, in volunteering to help others, or in any endeavor that creates a sense of purpose and brings older people in contact with others.

Clearly, one of the hardest things about growing older is loss – loss of friends and partners whom we outlive. In observing my father, I saw that when many of his contemporaries had passed away, he continued to be surrounded by younger people of all ages who were both inspired by him, and revered him as the “elder” in Buffalo’s labor movement and theater community. I believe that this buffered the pain of overwhelming loss, and provided a critical community of friends and colleagues who sustained him for many years.

How can we create a sense of community – through family and friends, or a social or political group, or an artistic endeavor – that engages us, provides support when needed, and challenges us intellectually?

Aging is not lost youth but a new stage of opportunity and strength.

Betty Friedan

Age is an issue of mind over matter. If you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.

Mark Twain

I was always taught to respect my elders and I’ve now reached the age when I don’t have anybody to respect.

George Burns

by Mindy Fried | Mar 14, 2011 | family, loss, social justice, value of caregiving work

Joan and Warren lived next door. They were in the first-floor apartment of a modest, fading yellow, two-family house. Father and daughter, they had been living in that apartment for some 15 years. Before that, they lived in an apartment down the street, but the landlord raised the rent far beyond their means, and gave them no option but to move out. At the time, the neighbors were outraged. In their neighborhood, they said, people stayed forever, so the idea that a landlord could throw out one of their own was antithetical to “how things were done around here.” Shunning the landlord, the neighbors banded together and found them another apartment right down the street. When Joan and Warren moved into the faded yellow two-family, they pledged never to move again. People lived their whole lives in this neighborhood. Why shouldn’t they?

Despite an age gap of 30 years, many people mistook Joan and Warren for husband and wife. Maybe it was how they related to one another; maybe it was how they finished each other’s sentences, or made similar sarcastic jokes with a twinkle in their eyes. Joan and Warren even looked alike. Not just a little alike, but a lot alike, with but a few distinctions. Warren was large and tall to Joan’s short and stout. Joan hid her plump body in old wool, Catholic-plaid smocks, and comfortable old sweaters that united any division between breasts and belly. Warren wore flannel shirts and baggy pants, held up by a worn leather belt that had an extra six inches hanging off the buckle. Both of them had chins that receded into their necks, doubling and tripling in folds of skin. But Joan’s chin was framed by curly, blond waves and Warren always covered his head with a railroad hat he constantly readjusted.

On the weekdays, Joan left early for her teaching job at a local parochial school, but after work and on the weekends, she devoted herself to her father. Despite her easy-going personality, Joan didn’t seem to have many friends. In fact, Warren – her father – appeared to be her only friend. Since Warren’s knees “went” on him years ago, as he told me, he wasn’t able to walk very well, so he rarely left the house. Despite his maladies and the relative sameness of his days, Warren managed to maintain a chipper demeanor, sitting on the front porch in good weather and watching the world go by. He was limited by his health, and rarely had visitors, but he always seemed upbeat.

According to Harvard University-based psychiatrist George Vaillant, who studied the lives of 824 men and women over a 30-year period, “objective good physical health (is) less important to successful aging than subjective good health.” In other words, older people continue to function pretty well, as long as they don’t feel sick, and while we didn’t know much about Warren’s health, he certainly did not project the image of a sick man.

My daughter once interviewed Warren for an elementary school project, one of those-talk-to-someone-who-lived-through-the-war assignments. When we rang their doorbell, we could hear Warren shuffling slowly to open the door, accompanied by the thump-thump of his cane. Opening the door with a welcoming smile, we could see that he was tickled we were there. And as we entered their cluttered, old-fashioned apartment, we were struck by the sweet smell of Joan’s homemade brownies she had baked for this special occasion. As my daughter nervously prepared to ask her questions, Warren said self-deprecatingly, “What do I have to say?”, with the emphasis on the word, “I”. And then he launched into stories of his past.

After the interview, I didn’t see Joan and Warren for a few weeks. Joan’s schedule was hectic, she told me one day, when we ran into her. The end-of-the-year school party was coming up, and her kids were “goin’ nuts,” she said. And then she chuckled, letting us know that she actually liked the chaos of her kids going nuts. She also told me, almost in passing, that her landlady, who had been in a nursing homes for many years, had just died. This meant that the owner’s family would have to decide what to do with their house. It had never occurred to me that Joan and Warren might face another change…

But pretty soon the activity around the house picked up, as estranged family members began to lay claim on items they had inherited. Hungrily, they dragged out furniture, appliances, aged stereo equipment and pottery, hauling them into station wagons and SUVs. They also discovered that what used to be a working-class neighborhood many years ago had become a gentrified, sought-after neighborhood; and what had been an inexpensive house many years ago had soared in value. Rumors began to fly about what the family would do with the house. Would they sell it? Would one or some of them move in? And what would happen with Joan and Warren?

Finally, the house went on the market, and for two weeks, hoards of buyers came and went, gliding with ease through the upper two floors of this simple home, its rooms clean and ready for the next owner. They seemed to save their perusal of the first floor until last, more daintily tiptoeing through Joan and Warren’s apartment, which was cluttered with memorabilia, dusty with age and daily living.

When they reached the living room, there sat Warren, firmly planted in front of his television set, refusing to move to make it easier for real estate brokers to “show” the house. He was a part of the house, almost seemed like he came with it, one might say. So why should he move, just so some rich people could sashay through the house, looking at its “potential”. As the days progressed and no one had ostensibly made an offer on the house, there was rumor that maybe the market had slowed down. But after a couple of weeks, the house sold at a good profit.

Joan and Warren hoped that the new owners wouldn’t raise the rent, but they were getting nervous. When I saw Joan the next day, her eyes were red and her face bloated. “What will happen now?”, I asked. She shrugged, looking embarrassed. “I’m not sure, but the new people seem pretty nice,” she replied. Maybe they would stay, I thought, feeling more hopeful for them. I wished her “the best of luck,” then felt the emptiness of those words. Shortly after we spoke, Joan got into her car and drove off to work.

When she drove back into her driveway later that day, her car was filled with empty boxes, in anticipation of the inevitable move. She slowed her car down for a group of kids playing soccer in the street, and waved first at them and then at the parents who were monitoring them. Slipping into her house, she self-consciously avoided conversation, but the parents on the street were painfully aware of her presence and concerned about both her and her father. Another parent and I started talking about helping her find a new home, but our conversation was interrupted by a piercing scream, coming from inside their home.

Somehow at first, the kids didn’t hear it. In the midst of their game, maybe it seemed like just another loud sound. I ran to Joan and Warren’s front door, which was ajar, and let myself into the apartment. And there, on the floor, was Warren, lying motionless, with Joan lying on top of him, sobbing…

The next few hours, we all learned that Warren had died of a heart attack. The younger kids were initially oblivious, but the older ones, particularly my daughter and her best friend, began to cry. The cries became wails that were deep and loud and persisted for about an hour, capturing a raw grief that many of the adults shared but couldn’t express so freely. As the ambulance came and took Warren away, the younger ones were shuffled back to their homes, perhaps to protect them from that visual impression, and certainly to respect Joan in that painful moment.

Would it be too simple to say that gentrification killed Warren? It would be hard to make the causal connection, but perhaps there is a correlation, as Warren was forced to experience the stress of losing his home, again. Ironically, Warren was right when he claimed that this was going to be his last home. Ultimately, the power of the market won, as the highest bidder got the house, and with it, the legal right to determine whether or not to raise the rent, or for that matter, to take over the whole house. That evening, my daughter remembered that she had the tape from her interview with Warren, and asked if she could give it to Joan. “Sure,” I said, “but let’s wait a little while.”

by Mindy Fried | Mar 3, 2011 | family, loss, memories, organizing, social justice

My father just died. My 98-year-old, fearless, outspoken father – who was devoted to fighting for the rights of workers – just died. He hung on for over a year, despite major organ failure, with incredible determination and will. Just the way he lived. Even towards the end, despite the challenges and limitations to his body and mind, he was energized by the protests in Wisconsin, as state workers – police, firefighters, nurses and more – fight to maintain their right to bargain collectively.

In the 40s and 50s, my father was unafraid to speak up for working-class people who toiled in factories. This was his organizing base, and as a child of the 50s, it seemed very foreign to me in my middle-class world. I was schooled by the antiwar movement, the women’s movement and gay/lesbian rights movement, all a far cry from the world of factory workers who made auto or typewriter parts.

In the 40s and 50s, my father was unafraid to speak up for working-class people who toiled in factories. This was his organizing base, and as a child of the 50s, it seemed very foreign to me in my middle-class world. I was schooled by the antiwar movement, the women’s movement and gay/lesbian rights movement, all a far cry from the world of factory workers who made auto or typewriter parts.

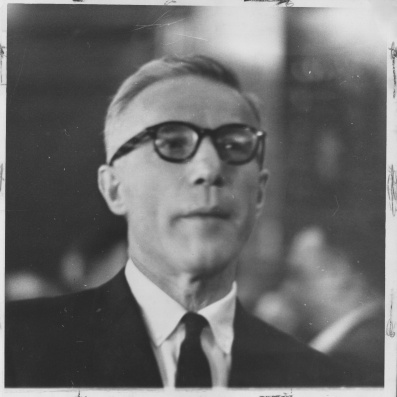

|

| Manny speaking before House Un-American Activities Committee 1964 |

|

But I absorbed my father’s social justice values, even though I felt very separate from the people he was organizing. It was hard for me to imagine the unfortunate plight of the factory worker, but over the years, I began to understand the need to fight against inequities around workers’ wages and working conditions. And once I was in the work world, I learned first-hand what it meant to be caught in a stratified social structure that appropriated varying amounts of power to its employees. In fact, a string of lousy work experiences was one thing that inspired me to study workplaces once I became a sociologist. I discovered first-hand that worker control is the key to job satisfaction, and many people don’t have enough of it…

I was once on a plane with a factory owner, and over the course of our flight, discovered that this guy’s plant – Remington Rand – was one that my father had organized. Listening to him talk about how he decided to move the company abroad, and how he couldn’t understand why his workers weren’t willing to move with him, I realized how out of touch he was with the reality of his workers. I knew more about him than he could have possibly known. My father had led the workers employed by that man in a successful strike against the company, and the workers forced the company to back down on cutting wages and benefits. I decided not to share this information, but found great satisfaction in knowing…

At my father’s funeral this past Sunday, I told the congregation that if he were still alive and well, he’d be in Wisconsin. This was his fight, something to which he dedicated his life, through his organizing work, and then later through plays he wrote about worker-management struggles. The nature of the “working class” is different today, as factory work has moved to locations with cheaper labor. Wisconsin workers represent the “new” working-class, whose self-identification is folded into our broadly defined middle-class. They are service and professional workers who provide the critical supports to our society – regulating safety, putting out fires, teaching our children, maintaining our sewage systems, and caring for the sick.

There are far too few heroes these days, people who are willing to stand up against adversity to speak their piece and demand justice. My father chose to do just this. It wasn’t always easy to have a father who prioritized the outside world over his family. In fact, I learned early on that if I wanted to be close to him, I had to speak his language. I tried very hard – sometimes too hard – back then. And the older and more knowledgeable I became, the more I realized where we differed. But at the very base, I valued his commitment to a set of ideals, even when they created adversity for him and for us. He always hoped that we would see he made the right choices. And in the end, as a daughter to a loving father who became more emotionally generous with age, I feel that he did.

|

| Manny receives Joe Hill Award from AFL-CIO Labor Heritage Foundation |

by Mindy Fried | Jan 31, 2011 | family, loss, value of caregiving work

This past weekend, I visit my nearly 100-year-old dad who is now in home hospice in an assisted living facility. With several major organs failing, he remains the perennial survivor. As a literary guy, he always used to quote Dylan Thomas, saying: “Do not go gentle into that good night.” And he continues to hold on…

I leave his apartment after my visit, feeling both a sense of relief as well as a deep sadness, even though I know I will see him in two weeks (assuming…), and that meanwhile, he is being well-cared for. As anyone who has taken care of an older person knows, caregiving is stressful, and caregiving from afar has its special stresses.

The ride to the airport is straightforward in this small city. It’s always a bit nostalgic as I pass by my father’s old house, where he continued to live alone up until two years ago, when we moved him into assisted living. As I pass the old street, I call my husband to let him know my plane is delayed, ignoring the state’s anti-cell phone law. (Okay – I know it’s unsafe, but I was at a stoplight!). And then it happens – BOOM!

I feel my car being hit from behind. I say matter-of-factly, ‘Oh my G-d, I was hit. I’ve got to go.’ And then my car gets hit again! I manage to move into the next lane, and this car keeps charging forward, hitting the car that was in front of me.

I jump out of the car, realizing that I’m okay, but see that my rental car is not. The driver responsible for all this reckless bumper car action is an older man, probably in his 80s. I tell him to pull over and then follow him. Turns out that he had put his foot on the accelerator instead of the brake! He claims that his foot was stuck. He is on his way to visit his wife’s grave. She had died six years ago, and he has borrowed his son’s car to get there.

The front bumper on his car is mottled, but aside from being stunned, he isn’t injured. Of course, what happens with him and his son is their next chapter, not mine, and I can only imagine. (Will the man continue to drive? With the son lend him his car? I hope not…) With this crash, we are connected by our humanness – this elderly man who is grieving for the loss of his wife, and I, who am grieving for the gradual loss of my father.

But there isn’t time to meander. My flight is leaving soon. I get advice from the rental car company about information I need from this guy, and after well wishes, I move on, driving down the highway, with half of the bumper hanging off my rental car.

As I enter the airport roadway, I call the rental car company. Like relay racers, they are ready and waiting, as papers fly between us and I gather my luggage. Running to the ticket counter, I arrive out of breath, only to be told that boarding for my plane is closed, and it’s too late to get on the flight. I plead for the airline worker to do something, sputtering fragmented sentences about my dying father and my accident. Just an instinct to use a sad story to manipulate authority… And then out-of-the-blue, another kind airline worker intervenes and calls the gate and tells them to hold the flight for me. Just for ME!

They tell me to HURRY to the gate! I get through security as quickly as one can get through security, run up to the gate, heart beating wildly, and apologize to the airline worker for holding up the flight. She looks at me whimsically, and says with humor, “Oh yeah, the whole flight is waiting just for you!” It turns out that they have not even started to board the plane. In fact, I have about 20 more minutes to wait. With that relief, I blurt out my story again, and this time, start to cry. For a moment, she looks me straight in the eye, and then she wraps her arms around me, saying, “I’m such a softy. I feel like crying with you!” And we do. Me and an airline employee!

Today, the airline gave me a $50 credit for the “inconvenience you recently experienced with us.” So thank you, Jet Blue worker and thank you, Jet Blue.

But most of all, I am grateful that in the midst of the challenges of caregiving, I have encountered people – strangers – with whom I connect, who gracefully help to diffuse those challenges.

by Mindy Fried | Aug 4, 2010 | gardens, loss, memories

As the summer is hitting its peak, our garden is proliferating with cherry tomatoes, two different kinds of lettuce, green peppers, herbs and more… I can’t take credit for it, but I certainly do appreciate it! I’m also appreciating the increased interest across this country in local foods, eating healthy and the pinnacle of city gardens: farmers markets. It is VERY exciting that Boston will soon (1 1/2 years soon) have its own downtown farmers market, following in the footsteps of other cities like Philadelphia, Seattle and San Francisco.

But when I think of gardens and gardening, I am reminded of my cousin, an amazing gardener and gifted health care professional, who passed away over 3 years ago after struggling with lung cancer. Here is a poem that I wrote a couple years ago, following his untimely death…

Treatment stopped and powerful medicines eased the pain

So we sat on the porch on that crisp fall day

Atop the sloping hill, gazing at the garden below

Childlike in our wonder

Timeless in a moment of joy,

Feeling the warmth amidst the cool breeze

Wind chimes serenading us gently.

“Should I live another year”, you said,

“I’ll build a new bed

and get rid of those tall plants to let in more sun”.

Speaking quietly but resolutely,

as we sat on the porch on that crisp fall day.

Looking down at two tall grass-like reeds,

Surveying the garden and envisioning a valley of colorful abundance.

For the past two summers,

a cadre of family and friends have labored hard on this sacred land

Honoring your life and spirit with rakes and trowels, weeders and hoes,

Sprinkling the hills and valleys with greens, oranges and reds

that provide solid ground to your two young children.

Who grow stronger every day,

as they dig their fingers into rich, brown soil

that channels memories of their father through their tiny hands.

You had a plan when you surveyed the garden

from the porch on that crisp fall day

A moment of joy before things turned

The cool breeze and warm wind harmonizing

in a chorus of chimes and tears

Capturing a moment that continues to breathe

into that hallowed garden plot of land.