by Mindy Fried | Jan 5, 2011 | family, knitting, value of caregiving work, women and work

My grandmother survived the pogroms of Eastern Europe, a solo journey to America at age 13, and my grandfather, who is one of the grumpiest men I’ve ever met. But until the day she died, just shy of 100 years old, she was an avid knitter, spewing out afghans, sweaters and socks to keep her brood of nine children clothed and warm. Lucky me received one of her gems at age 20, a very tidy little blue cardigan that I have to this day.

I never really thought of my grandmother when I started to knit. It just seemed like a fun thing to do with my daughter, with whom I used to “co-knit” scarves that were more about process than product.

Several months ago, a friend, whom I will call my “knitting guru”, pulled together a group of women to knit caps for a special neighbor friend who was going through chemo. I was driven by the mission and inspired by the camaraderie of the group, and managed to make several hats for our friend. They were full of flaws, but beautiful, nonetheless (if I do say so myself!). We all read Kyoko Mori’s book, “Yarn: Remembering the Way Home”, a memoir that is framed by lessons she learned from her knitting experience. I was most touched by her recognition that mistakes are okay. I realize that this sounds pretty basic! But somehow knitting lends itself to metaphors that speak to the heart. For example,

* Individual pieces of yarn weave together and create something beautiful and new.

* Sometimes, when you make too many mistakes, you just need to undo what you’ve done and start over.

* When a ball of yarn gets really knotted, it takes a long time to undo the knots.

See what I mean? Once I got the knitting bug, I discovered a world of knitting addicts (we are everywhere!) who find pleasure – as do I – in color and texture, and creating usable objects that people want to wear! What a concept! I also discovered that the process of knitting is meditative, relaxing, invigorating, all-consuming, jitter-reducing, anxiety-protecting, and creative. Once you’ve gotten past stage one, you can actually talk and knit, which is also incredibly satisfying…

When I told my college-age daughter I had started to knit again, she expressed concern that I was – in short – getting old. Despite my arguments that knitting was the “new cool”, she had conjured up images of me as a doddering old grandmother, content with my yarn and needles. Alas, when she saw the hats I was making, she put in a request for a sweater, and lo and behold, she started to knit too!

My first three hats went to my friend who had lost her hair. The next three were sold to neighbors during an “open studio” event, in which people stroll through the ‘hood and view art on display in and around people’s homes. These folks actually paid money for my hats! The next batch went to my family. My father – nearly 100 years old – had moved to assisted living and I had started flying to visit him every other weekend.

I made four hats for the cousins who house me when I’m visiting him. They call them their “Mindy’s.” I’ve made five hats for my immediate family, including my husband and sister. And I finally made a hat for my father, who, after seeing all this knitting action, said he’d like “a Mindy” for himself. I also made several hats for my daughter’s friends and a neighbor. The next few hats will be for the amazing people who care for my father nearly 24/7, keeping him alive with their love and attention.

When I think I’m done making hats – after all, there are a lot of other interesting things to make – someone else puts in an order. And I’m grateful for it…

by Mindy Fried | Dec 19, 2010 | management policy, policy, positive work culture, productivity, women and work, work and family balance

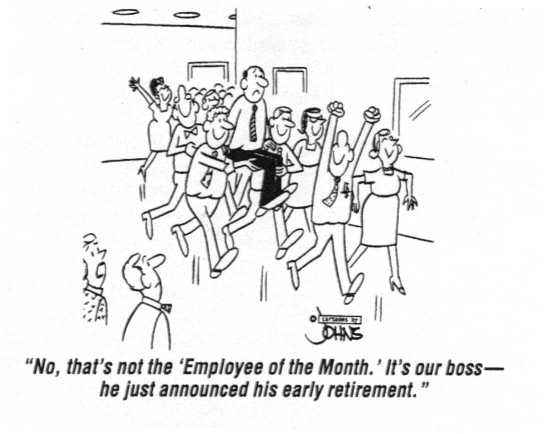

We’ve all had them, and maybe some of us are them! (No, not us!) As a sociologist who has spent many years studying workplaces, I am indebted to a number of bad bosses. Although some of them made my life miserable, they inspired me to understand why. So in the spirit of acknowledgment, I must first say thank you to the boss who told me I was destroying my life by leaving the job to pursue another direction. (Destroying whose life?) And thank you, too, to the psychotic boss who knew that I supported a particular political cause, and out of nowhere screamed at me, “Don’t ever let me see you on television with a sign in your hands supporting that Communist (crap).” Whoa! It hadn’t occurred to me, but now that you mention it…And thank you to the newly appointed manager who, in her first month on the job, falsely accused me of serious financial improprieties. (One month, and many sleepless nights later, I was vindicated.)

Given these experiences, it has been therapeutic to study the American workplace and to dissect some of the problems that contribute to “bad-bossism.” Despite having been “stung” by a few bad bosses, I still believe that people – including some bad bosses – are basically good.

So what is it that leads some people in management positions to “behave badly?” Well for a start, the workplace is a microcosm of our larger culture and society. Societal problems that exist outside the office are likely to surface within it as well, playing out via power dynamics between and among employees, based on their occupational status, their gender, and their racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Political economist and philosopher, Karl Marx, laid the groundwork for understanding the intrinsic tension between labor and management (or, as he would say, capital), in which a capitalist system favors profit over people. In this system, he argued, management would necessarily exploit workers with long hours and poor working conditions, in order to get more productivity out of workers, which in turn would maximize profit. With the advent of laws that limit working hours in manufacturing settings, and the regulation of working conditions, Marx’s critique and analysis continues to provide a useful framework, even though it’s probably more relevant to manufacturing work in Third World countries, where many multinational corporations have moved their operations in search of cheaper labor.

In the U.S., our current economy has increasingly shifted to knowledge-based work and services, and the lines that are drawn between workers and managers are often painted as more subtle. Nonetheless, stratification of the labor force ripples through multiple levels of professional and managerial workers. How do these dynamics affect the contemporary workplace?

Studies suggest that a number of factors shaping workplace environments contribute to the “bad boss” phenomenon:

1. Male model of the ideal worker

In this model, the “normal” trajectory of the worker is based on a “male model” of the ideal worker, a person who can work throughout his (her?) career in a continuous and uninterrupted manner, taking no time for non-work (e.g., personal, family) activities. Sociologist Erin Kelly, et al calls it a “masculinist work culture”, commenting,

“Working long hours is a sign that employees are readily available and eager to meet others’ needs; it further reinforces the ideal worker as someone – most often a man – who does not have, or does not attend to, other pressing commitments outside of work.”

With this model, work comes first. When managers perceive that’s not the case for one or more employees, it’s viewed as an affront to the company, a deviation from employee loyalty. Managers who “buy into” a “masculinist work culture” are likely to be critical of workers who challenge this norm. In a study I conducted on parental leave policy in a large financial services company, the norm was so powerful that men chose not to use the company’s generous parental leave policy, and women who used the policy took very short leaves, even though legally, all employees were entitled to longer leaves.

2. Structural issues that create a culture of competition

in our current American workplace, where the bottom line rules, there are economic pressures to produce. In line with the prevailing capitalist ethic, a culture of competition is viewed by many managers as necessary to foster productivity, with long hours as the norm. In order to sustain productivity, managers feel pressure from above to push employees to produce more, even when they realize that it’s not humanly possible. In a number of the workplace studies I’ve conducted, I’ve learned that being in a middle managerial position is often isolating. This makes these managers depressed and grumpy. Most have little support to figure out a better way, and they realize quickly that too much empathy for their “subordinates” takes too much time. Ergo, they may “act badly.”

3. Poor economic times makes managers even more grumpy

In our crisis economy, the financial pressure is even more intense, and some managers may exhibit more controlling behavior towards their employees. Managers are being more closely monitored on financial performance, and they may be even less likely to take the time to attend to employees’ feelings or needs under these conditions.

4. “Deal with it; I did!”

Some managers worked hard to get where they are, and along the way, they experienced a lot of pain themselves. When they get to the top (or close to it), some pass on what is familiar. While many of the managers I’ve interviewed worked very hard to respond to the needs of those under their supervision, some were less than understanding.

5. Lack of management training

Some managers who are good workers are rewarded by being moved up to management positions. While some organizations prepare their workers for this type of promotion, others fail to prepare them for the pressures they encounter once they are in charge. Without adequate management training, some bosses make mistakes, even lots of mistakes. Sometimes they find themselves in positions of power and it feels uncomfortable. They’re being asked to do things with and to workers that they wouldn’t have liked themselves. They know that. But they don’t know how to challenge or work with the system without jeopardizing their reputation or losing their jobs. This can make for frustration and grumpiness.

6. Personality problems

Some managers just shouldn’t be managing people. Their “management style” may look good to upper-level managers because it fits in with a culture of competition and drive. But they may be making the people who work for them miserable. Because of an “us” and “them” dichotomy, other managers may even side with them.

Perhaps we all have a story about the crazy or mean or incompetent boss. Are all managers bad bosses? No, of course not. But the problem is clearly pervasive: Google “bad boss” and you’ll find over 7 million citations, with countless workers publicly venting about their negative experiences, and experts offering advice on how to deal with that mean and disrespectful supervisor.

What is a good boss? There’s plenty written about good bosses as well. Google “good boss” and you’ll find over 14 million citations! Hopefully we’ve also had them (and maybe even are them!).

Here’s an excerpt (slightly tweaked) from an 10/10/10 article in the Chicago Tribute by Mary Schmich about what makes a “good boss.”

* A good boss understands that all power is fleeting and borrowed, and doesn’t take advantage of this moment.

* A good boss realizes that her/his real power comes not from those above him, but from the rank-and-file.

* A good boss listens, and can see a problem before it turns into a crisis. If it does turn into a crisis, the good boss works with an employee to resolve the situation.

* A good boss understands that your time is important too.

* A good boss is a good communicator, responding to your concerns and questions in person and via electronic communications.

* A good boss treats employees with respect. S/he does not treat people differently based on their occupational status, gender, race or sexual orientation.

* A good boss tries to make everyone feel special and included.

* A good boss is self-aware and tries to understand how his/her behavior affects others.

* A good boss has the courage to deal with problem employees, and does it professionally.

* A good boss tells you when you screwed up and forgives you.

* A good boss does not take credit for your ideas, nor does s/he demand credit when s/he gives you an idea.

* A good boss is not afraid of people as smart as s/he is.

* A good boss sees what you do best, matches your job to your talents, and gives you room to bloom.

* A good boss remembers how s/he felt about bosses before s/he was one.

* A good boss reveals just enough about her/his personal life to remind you that bosses are people too.

* A good boss doesn’t take bonuses when the workers can’t get a raise.

* A good boss knows how to apologize and how to laugh, sometimes at him/herself.

* And a good boss understands how much we all yearn for a good boss.

by Mindy Fried | Dec 8, 2010 | productivity, women and work, work and family balance, work statistics

I just wrote the following piece for WorkplaceFlexibility.com.au, based in Australia. Thanks to Juliet Bourke from Aequus Partners for allowing reproduction:

After considerable debate, the U.S. Congress has finally approved the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010.

The Bill, which has passed both the House and the Senate, is now awaiting President Obama’s signature. Once that happens, federal agencies will be required to develop a policy that allows eligible employees to do at least some portion of their work outside of the office, with the aid of electronic communications. Agencies will also be required to incorporate this alternative arrangement into its operational planning for natural and other disasters.

Why it’s a no-brainer…

There is an abundance of research data demonstrating the positive effects of teleworking – or telecommuting – on employee well-being and on the employer’s bottom line. In a “meta-analysis” of 46 studies of telecommuting involving 12,833 employees, Pennsylvania State University psychologists, Ravi Gajendran and David A. Harrison, found that telecommuting was a win-win for both employees and employers.

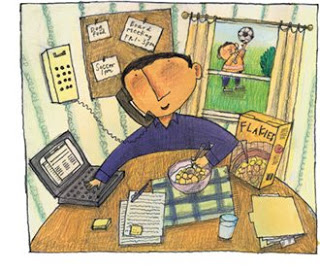

Telecommuting gives employees a sense of freedom at work, which contributes to job satisfaction. It reduces stress and helps workers balance their work and personal responsibilities. Employees who telecommute maintain and increase their productivity. Having access to telecommuting increases workers’ loyalty; and working outside of the office for one or two days per week has no negative effect on employee relations with coworkers or managers.

Gejendran and Harrison’s findings reflect what I learned in a small qualitative study of women telecommuters who were employed in several major American corporations. Despite the dramatic influx of women into the paid labor force in the past few decades, they continue to be the primary caregivers within their families. With inadequate government family policies in the U.S., and the limited response within the private sector to employees’ family concerns, our society is experiencing an enormous care gap. Telecommuting provides women – and increasingly men – with a legitimate avenue to combine and/or accommodate their market work and caregiving responsibilities.

The women telecommuters I interviewed claimed that the arrangement improved their work-life balance, allowing them to have more control over when and where they performed their work. At the same time, telecommuting helped them to maximize their productivity, serving the ultimate objective of employers. One telecommuter I interviewed for the study told me that she was able to maintain her work, despite dealing with a serious health problem.

“I’ve just been diagnosed with breast cancer, so about a month ago I had surgery and now I’m getting radiation every day, and in the summer I will start chemotherapy. So being a telecommuter is enabling me to work from home if I’m not well enough to come into the office.”

And a manager of a customer service department told me that telecommuting, while supporting employees’ needs, also benefited the company’s bottom line. Describing his rationale for implementing a telecommuting policy in his department, he said,

“People can do the same thing they can do in the office at home and save them the wear and tear of coming to work, the wear and tear of a long commute in many instances, maybe tolls… schlepping around with the kids trying to go to a child development center. The company benefits to the extent that every time we have a bad weather close-down, we have people on the phone at home instead of disruption of service. So it’s a win-win on both sides.”

Trial run in the States…

Indeed, telecommuting has been instituted in a number of U.S. federal agencies already, as well as in numerous corporations. In a 2004 study of 74 federal agencies, 43% of employees (323,292) reported that they were eligible to telework, compared to 35% of employees (625,313) in 2002, representing a gain of more than 20%. And in the overall U.S. labor force – including public and private employers – it’s estimated that more than 33.7 million workers telework at least one day per month.

Moreover, 22 states have already passed telework legislation. A number have implemented these policies to address environmental concerns or traffic congestion; some states encourage private employers to implement telecommuting programs; and others have statutes connecting employee productivity and efficiency to telecommuting, or promoting “a better quality of life.”

Historically, many federal policies in the U.S. are first implemented at the state level. This was the case for Social Security, health care reform, maternity and parental leave, and even civil rights legislation. The federal legislation was the culmination of pressure in smaller policy environments. But having a federal bill can also provide a model for more universal implementation. In addition to creating a mandate for federal agencies, hopefully the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 will provide encouragement for additional states and private sector employers to institute or expand their telecommuting policies.

Making the Bill real…

While the effects of telecommuting are positive for employers and employees, it is only workable for certain types of work and with certain employees, and therefore not a universal solution to problems in workplace policy. But it is particularly well-suited for those doing “knowledge work” that can be effectively performed in multiple locations with the help of electronic communications.

Even for those who have jobs that are conducive to telecommuting, the face-time culture of most organizations may undercut its utilization. It’s one thing to have a policy, and yet another to have employees use it. The Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 requires training for employers and employees, which is a critical element to shift an organization’s culture.

In my telecommuting study, I found that even those who felt supported for their work at home felt it was a privilege, and in turn, worked additional hours to “prove” their loyalty. But when they did use a policy, it improved their quality of life.

The cost/benefit debate…

The sad fact is that Republican opposition to the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010 is not based on what’s good for employees or employers. It simply affords Republicans another opportunity to say that less government is better. But that argument doesn’t make sense if the policy is administered with care. Representative Virginia Foxx, a Republican legislator from North Carolina, argued that with a high unemployment rate, it is a “travesty” that Democrats are “pushing this initiative to make it easier for federal employees – who already have it much easier than the rest of the country – to avoid the office.”

Rep. Darrell Issa, a Republican legislator from California, said that the law adds a layer of bureaucracy into federal agencies, claiming that Americans want less government. Bolstered by recent elections of conservative Republicans to Congress, he says, “This will be the first vote after the American people said no to government waste, fraud and abuse, government growth and government spending.” Issa will undoubtedly try to amend or change this legislation when he begins his role as the new Chair of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. According to the New York Times, Issa’s plans are part of a larger Republican agenda to vastly expand scrutiny of the Obama administration and aggressively push to cut spending and shrink the government, focusing on “excesses and waste.”

Democrats who supported the passage of the telework legislation provided evidence regarding its cost-effectiveness. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that implementing the bill will cost around $30 million over five years, but the return on this investment will pay off over time. Representative Stephen Lynch, a Democratic legislator from Massachusetts and my very own Congressional representative, said the long-term savings will provide an “excellent return” on this initial investment. And indeed, the experience of many private companies suggest that he’s right on the money. IBM has saved as much as $56 million annually and reduced office space by allowing employees to telework; Cisco generated an estimated annual savings of $277 million in productivity by allowing employees to telecommute. And IBM Canada currently saves $20 million in operating costs annually and over 500,000 feet of real estate with its telework program.

Let’s hope that sanity – backed up by plenty of data and experience throughout the U.S. – will prevail once this sensible piece of legislation is signed by the President, and that the resistance will be met with reason.

by Mindy Fried | Nov 21, 2010 | child care, early education and care, family, parental leave policy, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, work statistics

Yesterday, I shared a long plane ride with a Japanese woman who was coming to the States to visit a friend. She patiently helped me try to track down an old Japanese friend via Google. Yes, there was WiFi on board; yes, Google in Japanese is very cool; and no, we were not successful in tracking her down! But more importantly, we talked about work and family issues, as she described the gendered division of labor in Japan. She is employed as a translator, but took a 10 year hiatus from her paid work – actually quit her job – to care for her son. This is typical, she said, among women “in her generation.” (After our conversation I calculated her age as around 43.)

In his book, The New Paradox for Japanese Women: Greater Choice, Greater inequality, Japanese economist Toshiaki Tachibanaki presents a gendered analysis of the Japanese economy. He reports that while Japanese women now have more choices in their careers than in earlier days when their education consisted of preparing them to be “good wives,” they now face job discrimination, sexual harassment and wage inequalities on the job. My new Japanese airplane friend commented that her husband wanted her to stay home with her son, telling her that it was the most important thing she could do. He, on the other hand, was working 12+ hour days. When I asked her if he was “able to” spend time “at home,” she winced and said that he did play with their son sometimes, but didn’t do any housework or cooking.

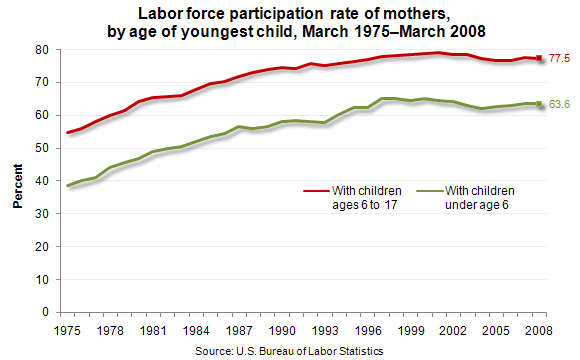

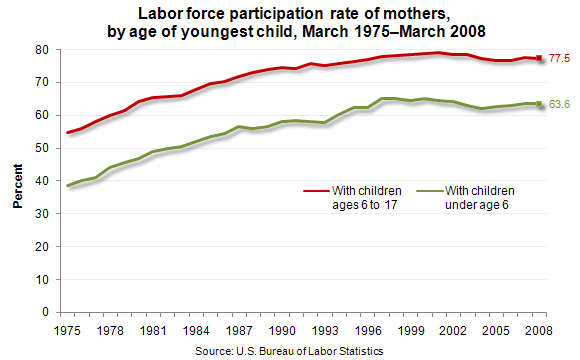

She was surprised to hear that over 75% of American mothers of school-age children work for pay. In Japan, nearly half of all women work in the labor force, but Japanese women earn less than half of what men earn. So it’s no surprise that women take on the brunt of the caregiving responsibilities, simply from an economic perspective. By the way, the gender wage gap in the US also is a significant problem, particularly for mothers, albeit less stark than in Japan.

She also described the dissolution of the extended family in which multiple generations lived together. Without a grandparent to do childcare, women in Japan have a harder time sustaining full time employment.

While we didn’t dive into a discussion of childcare policy in Japan, her observation got me thinking about the meaning of community and the gendered division of labor during my childhood years in the 50s. The 1950s in the U.S. are portrayed much like my Japanese friend’s description of contemporary Japanese culture, with the general assumption that mothers’ most important work was to stay at home with their children.

But what did staying at home actually mean in 1950s America? I know from personal experience, as a child of the 50s, I spent hours playing on the street with my friends. Whether it was kickball, dodgeball, relay or two-person races, or making up plays, we kept each other busy (on the street, as opposed to off the streets!). When I wasn’t in school or hanging out with my buddies on the street, I was taking dance classes or piano lessons. And when I wasn’t in school, on the street or at a lesson, I was firmly planted in front of our black-and-white TV, watching “traditional family life” in shows like Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best, and Ozzie and Harriet. While my mother was a “stay-at-home” mom, like the majority of middle-class mothers in that era, she and I didn’t spend a whole lot of time together because, frankly, I had other fish to fry!

Despite the glorification of family life in 1950s America, believe it or not, mothers today spend about the SAME amount of time as the 50s and 60s moms who did not work outside of the home! Family sociologist Suzanne Bianchi found that while the number of children with mothers in the paid labor force has gone up considerably between 1965 and 2000, there has actually been a slight INCREASE in the amount of time moms are spending with their children over these years now – from 10.6 hours per week in 1965 to 12.9 hours per week in 2000. Contemporary dads also spend a little more time with their kids these days, from 2.6 hours per week in 1965 to 6.5 hours per week in 2000.

So what’s the deal? Well it looks like a number of factors have converged to create this new reality, even though mothers and fathers spend a lot of time at their paid jobs. First of all, the work of the “at-home” mother has been greatly altered by technology and fast food. Meal preparation – especially when it comes from a takeout joint, comes out of a package, or pops out of the microwave oven – takes less time. Mothers are also spending less time cleaning the house, compared to a few decades ago. Dust bunnies prevail! And actually, fathers never spent a whole lot of time cleaning the house anyway, so no big change there.

But equally important, the notion of good parenting has shifted over the years from more hands-off to more intensive, involved parenting. From playing classical music to your in-utero fetus to knowing all your kids’ teachers to coaching her Little League team to texting daily with college age kids, the contemporary notion of “good parenting” has been redefined as engaged parenting. Based on the research, it seems that mothers who work outside the home want to “protect” the amount of time they have with their children; ergo, spend as much time with them as possible.

In her study of nurses who work night shifts, Anita Garey found these women chose night hours so they could maintain the notion of the “ideal mother” who was available to meet during the day with her child’s teachers, bake for the bake sales, and show up at school events. All this came at a cost: sleep and personal care. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild called this phenomenon the “time famine.” Bianchi argues that the increase of mothers in the paid labor force, at least in two-parent families, has shifted some of the caregiving responsibility to fathers, commenting,

“Perhaps most controversial, women’s reallocation of their time probably has changed men. The increase in women’s market work has facilitated the increase in women’s involvement in child-rearing, at least within marriage.”

Clearly, the economy is the driver in the U.S. and other parts of the world, creating an imperative for women to participate in the paid labor force. But women, like men, derive meaning from paid work, and the women’s movement of the 1970s – while rarely mentioned these days – had a powerful impact on women’s sense of entitlement in the workforce.

While we are not battling the level of tradition that exists within Japanese culture, we have a long way to go to achieve equity, particularly for mothers in the paid labor force.

To achieve real equity in the labor force, we need concrete changes in government policies that promote and protect wage equity for women, and protect against gender- and parent-based job discrimination. We need a paid parental leave policy, and support for shorter work hours so that parents of young children can choose to gradually return to full employment after taking a parental leave from the jobs. We need universal child care so that all young children have access to high-quality early education and care, and not just those in families that can afford it. And we need universal health care, so that workers are not reliant on a job for their health insurance. That’s too dangerous in this economic climate, and even with employer-based insurance, there is too much variability in the type of care provided.

Tall order? Maybe, but we need a comprehensive set of solutions to achieve “good parenting” in this age of work-family imbalance.

by Mindy Fried | Oct 13, 2010 | child care, family, parental leave policy, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work

A sociologist buddy of mine just told me that she may be using my book on parental leave in a new class she’s teaching (Taking Time: Parental Leave Policy and Corporate Culture). While I should be overjoyed, I am not. Why? Because the book is 12 years old and it’s sadly as relevant today as it was twelve years ago!

Taking Time is based on an ethnographic study. In other words, I went native and hung out for a year in a financial services corporation I called Premium, Inc., studying its corporate culture. I wanted to understand how the culture of the workplace affected employees’ attitudes towards the company’s generous parental leave policy and ultimately, who used it.

I happened to be doing this study right after the passage of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA.), which was the first bill President Clinton signed in 1993. The bill mandates employers to allow their workers – women and men – to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to parent their newly arrived baby (biological or adoptive). This federal policy provided basic rights to Premium employees, in addition to the company’s own parental leave policy.

To my dismay, I found a strange and insidious blend of economics and culture that seriously undercut the use of parental leave policy at Premium. Of the 143 parental leave takers I interviewed, 140 were women and 3 were men! Women in high-level positions barely took leaves. In fact, only two female vice presidents took five weeks; the three senior female managers took five, nine and 10 weeks respectively. As one female senior manager said,

“Old-time management in the company still has an old mind-set about about women and work and family…The women who generally get to the higher top are the women who don’t have the children. You have to sacrifice something to get there.”

Not a single male senior manager took a parenting leave. Instead, new fathers tended to take 2-week vacations after the arrival of their new baby. One male manager I interviewed told me,

“It was simple economics. I was going to work full-time and (my wife) was going to work part-time. We joke about her job being a hobby because she’s hardly covering the cost of daycare.”

Most men facing new parenthood didn’t even consider taking time away from their jobs to parent a newly arrived infant, because they were worried their careers would suffer. For them, the cultural norms of the workplace mitigated against taking time to do what is still considered “women’s work”. Simply put, for both high-level female and male managers, babies and briefcases didn’t go together. This cultural norm trickled down to the organizational culture…

The largest group of workers who used the leave policy were women in non-management positions. Professional non-management women took an average of 10 weeks leave, two weeks less than the 12 weeks allowed by the FMLA! And nonprofessional women – women who earned less than those in professional positions – took an average of 8 weeks, with half taking 7 weeks or less. These women simply couldn’t afford to take longer leaves. Unless they had family lining up to care for their babies, much of their time was spent worrying about setting up quality, affordable childcare. This short leave-time falls far short of the six-month leave that T. Berry Brazelton, child development expert, recommends to support parent-child bonding.

In a 2009 study of current leave-taking practices, researchers found a a similar picture. There has been a very small increase in the amount of leave-time taken in the birth month (5.4%) by “highly educated and married mothers” and an increase of 13% in the next two months (Han, Ruhm and Waldfogel, 2009). Single mothers, on the other hand, are less able to afford unpaid leave. And fathers continue to take extremely short leaves or none at all.

This data confirms what I found in my study 12 years ago: that uppaid leave policy discriminates against those at the lower rungs of the income ladder who cannot afford to take longer leaves. With the absence of a mechanism to replace workers’ wages during the leave period, non-management female employees shorten their leaves; management employees take short leaves; and men don’t take parental leaves at all.

While lower paid workers would be the most obvious beneficiaries of paid leave, in fact, ALL employees would benefit from such a policy. The U.S. is the only wealthy nation in the world that does not offer parental leave, according to political scientist Janet Gornick, who conducted a cross- national study of parental leave policies.

“The United States has the least generous parental leave policies of all 21 economies compared in the study. We pay a high price for our meager policy, because parental leave improves the health and well-being of children and their parents, and paid leaves provide families with crucial economic support at such an important time.”

Gornick and her colleagues report that European countries, led by Finland, Norway and Sweden, rank far ahead of the United States in providing guaranteed parental leave, with Sweden ranking highest for gender equality and parental leave practices. Germany also offers a generous paid leave policy, and four countries show high levels of both generosity and gender equality: three Nordic countries (Finland, Norway and Sweden), and Greece.

We have a long way to go in the U.S.! California finally passed paid parental leave legislation in 2002, and the U.S. military even offers paid leave to its members. But a recent effort to extend paid leave to civilian employees got stuck in the Senate. And other initiatives to create paid leave through “baby unemployment insurance” – in which some small portion of the state unemployment insurance fund would go towards a paid leave fund – has hit a wall, given high employment rates.

Nonetheless, the issue will not go away for the thousands of mothers and fathers around this nation who want to spend more time with their babies.

It may seem counterintuitive to push for paid parental leave in this economic crisis, especially as people are being laid off from their jobs. You might argue that laid-off workers have more time to hang out with their kids anyway. And besides, why would employers want to add incentives for their existing labor force to take time away from the job? But those laid-off workers will return to the workforce when the economy improves, and those employers should care about creating humane work environments that don’t burn out their workers. And why shouldn’t we join the rest of the Western industrialized world in providing social policies that support mothers and fathers in the workplace?

Without a federal policy that provides the foundation of support for leavetaking, I fear that we will continue to see the patterns of leave-taking I found in my study twelve years ago. And that’s just not fair.

Meanwhile, my sociologist buddy asked if I could come to her class to talk about my book. I wish it were old news…

by Mindy Fried | Sep 30, 2010 | child care, depression, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, women artists

This is a picture of me and my mother. You’d never know from looking at the expression on her face that she hated being a “homemaker”. In fact, she looked pretty happy hanging out with me, even if we were washing dishes! In her younger years, prior to the birth of her two daughters, she wrote sultry torch songs and had her own radio show. Later, she studied painting and then continued to paint portraits until her final days. When I was a teenager, she exhibited her paintings every year in an outdoor art festival, near a studio she rented in what was considered the bohemian part of Buffalo, New York, my home town. Despite being an adolescent, this was the one and only weekend – every year – that I thought my mother was really cool.

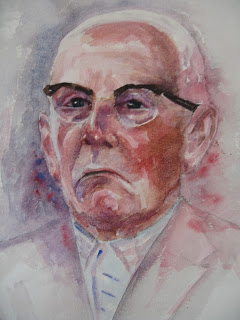

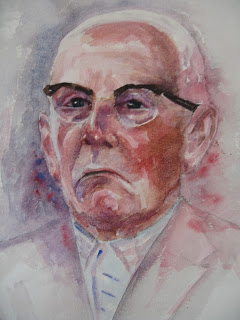

Here is one of her watercolors that I still really love. Middle-class women of my mother’s generation – caught between the suffragettes of the early twentieth century and the second wave of the women’s movement of the 1970s – did not have an organized “sisterhood” of women supporting them to step out of the kitchen. As an artist, my mother was passionate about her work, but it was never considered a career, nor did it generate much income, even though she taught painting and sold commissioned portraits. In fact, in her era of young motherhood – the 40s and 50s – single middle-class women who worked for pay were expected to leave their jobs once they were married. As we know now, the independence of women is often tied to their earning capacity, and not being considered a professional was hard on her. This phenomenon was eventually coined the “problem without a name” by Betty Friedan.

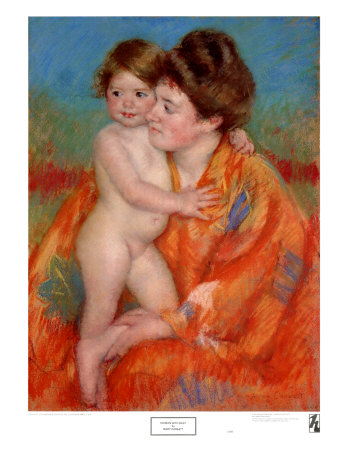

My mother’s favorite artist, Mary Cassatt, is quoted as saying:

“There’s only one thing in life for a woman; it’s to be a mother…A woman artist must be…capable of making primary sacrifices.”

How ironic, given that Cassatt never married, nor did she have children; and for many years she painted portraits of mothers and children!

Reflecting the schizophrenic existence of a strong-willed woman of that era, Cassatt also said,

“I am independent! I can live alone and I love to work!”

Even though her family objected to her becoming a professional artist, Cassatt began studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia – where my mother also studied art for one year. I never spoke to my mother about why she left, but Cassatt also left after one year, complaining that “there was no teaching” at the Academy. Unlike male students, females couldn’t use live models. This is likely just one of the inequities she encountered there. When she left, Cassatt moved to Paris. When my mother left, she moved back to Buffalo, New York…

My mother’s life was one of sacrifices, like so many women of her generation. The arts were a place for talented and creative women for whom other professional careers were closed. Maybe it was a vestige of the Victorian era when it was considered proper for upper-class girls and women to “dabble” in the arts. To be considered a serious artist was another thing though. And my mother always struggled to be considered a professional. It irked her when the realists or even the abstract expressionists – always male – won the competitions she entered. She intuitively understood that there was gender bias, but the proof was invisible. To be an artist means expressing oneself – putting one’s vision into the universe to challenge and inspire or simply to portray beauty. In an era where women’s voices were not heard, being a woman artist was revolutionary.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

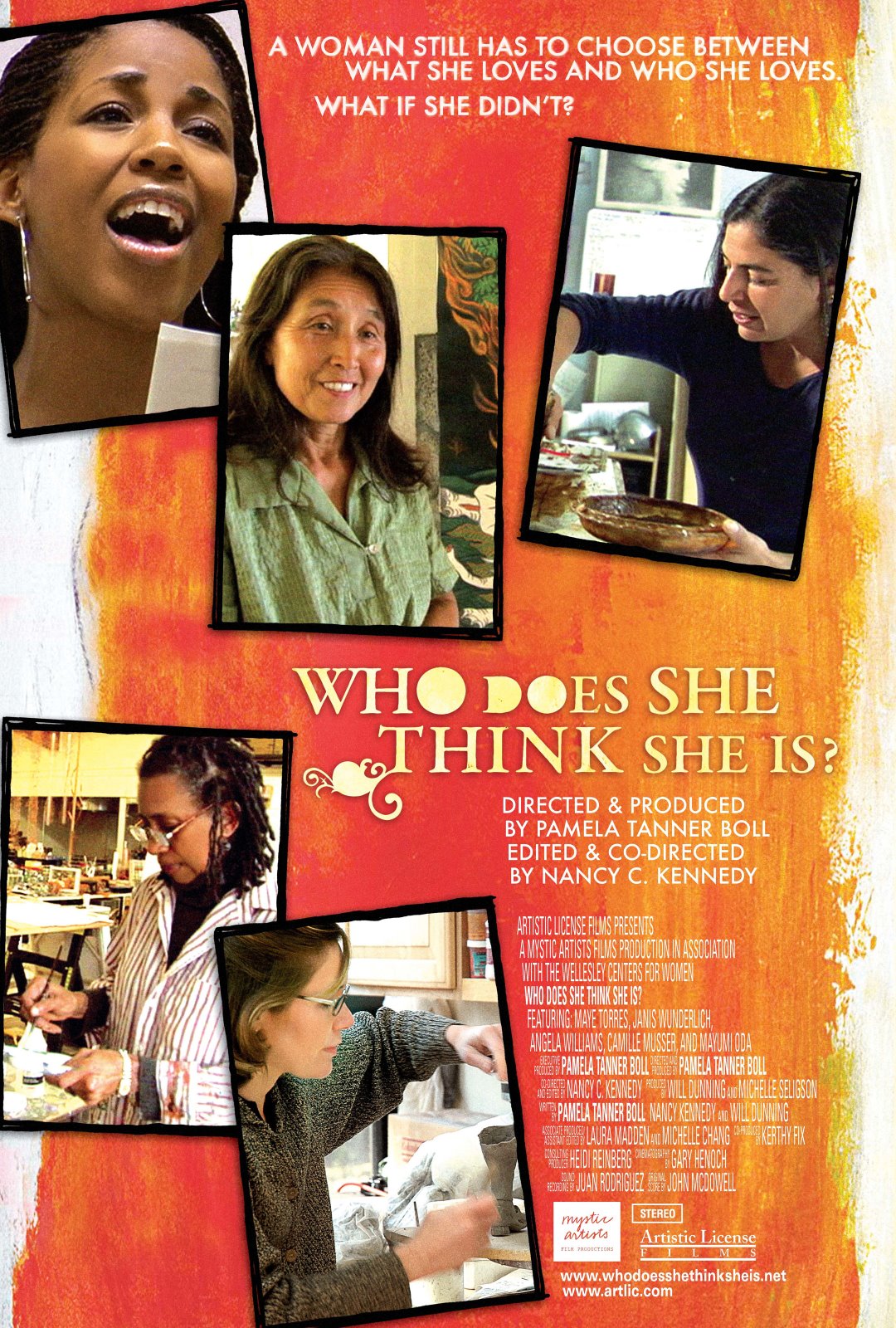

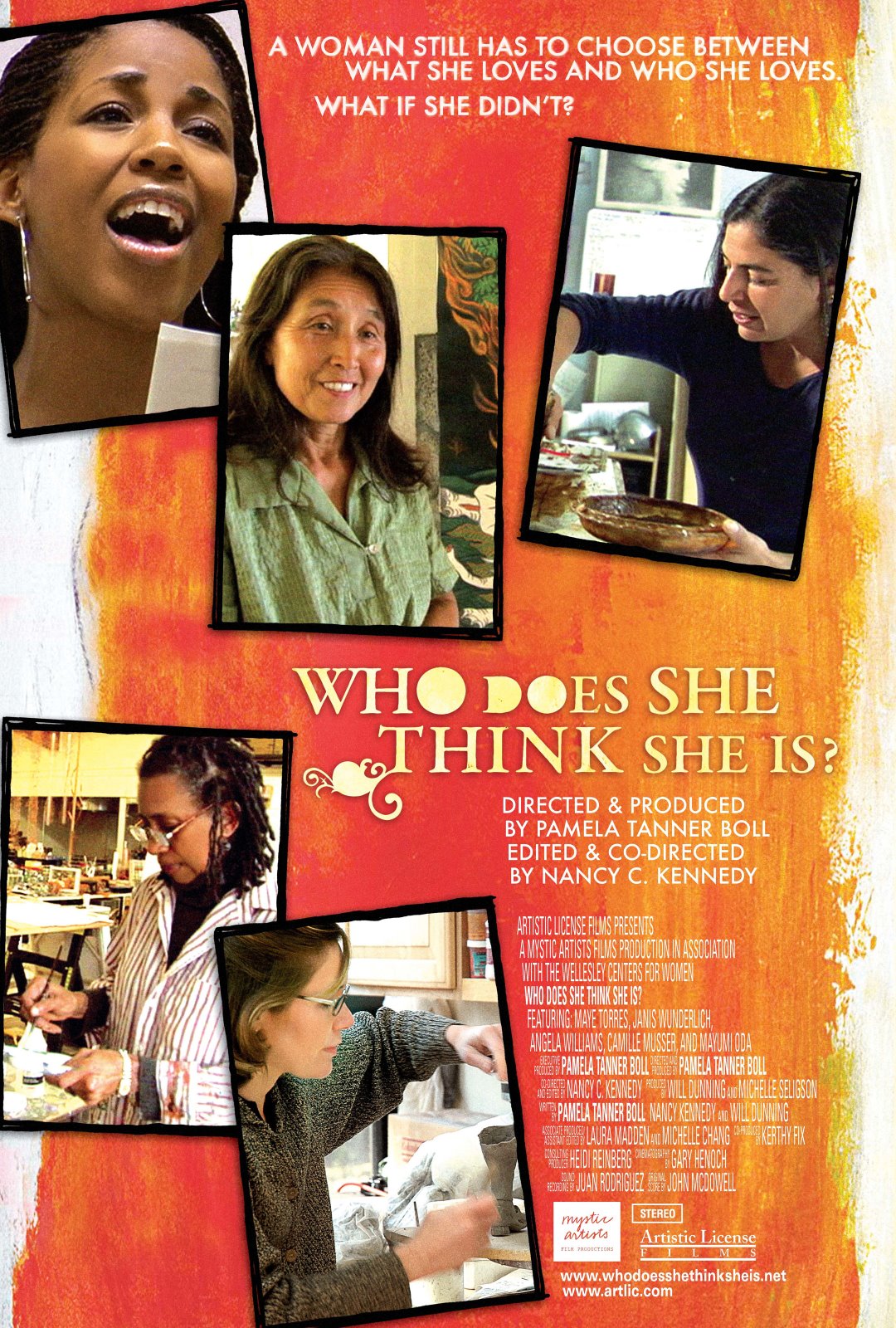

In a film about women artists called “Who does she think she is? – produced by Pamela Tanner Boll (who also produced Born into Brothels) – artists reflect on the challenges they face balancing their work and family demands.

They talk about how they’re not taken seriously precisely because they’re women. In fact, while 80% of students in visual arts schools are women, “in the real world,” 70-80% of artists whose works are shown in galleries and museums are male.

In an article in the New York Times, Marci Alboher says these statistics “sound alarmingly like the numbers released by organizations that track the presence of women in the highest echelons of professions like law, journalism, engineering or finance.” The women artists in the film also argue that they are dissuaded from focusing their art on the subject of mothers and children, because it is not considered “real” material. Both artist and subject are devalued…

Outside the art world, says Alboher, people rarely discuss the challenges faced by women artists “moving up the ranks.” This has a lot to do with the fact that women are still considered primary caregivers in this society. Despite the large percentage of mothers in the labor force, we are still defined primarily by our capacity to bear children. Most workplaces do not accommodate the need for work-life balance for their employees, be they women or men.

As a teenager, I was often frustrated by my mother’s lack of confidence in her work. I wanted her to be a strong role model in many ways, someone who followed her passion and knew she had talent as an artist. But now I have an increased understanding of the effects of working in isolation, in a society that didn’t value the work of women artists, and in the microcosm of that society, in a family that expected her to have dinner on the table every night. (No wonder she hated to cook!)

I love the comment by Georgia O’Keefe who once said,

“I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking the time to look at it. I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

It takes guts to think that your painting will stop New Yorkers in their tracks! But while guts are good, women’s voices need to be valued; the balance of caregiving must be shared; workplaces need to accommodate the work-life balance needs of parents; and social policy must broaden to include paid parental leave and universal, free early care and education.

According to a 2008 National Endowment for the Arts report called “Artists in the Workforce: 1990-2005”, women artists are as likely to marry as women workers in general, but… they are less likely to have children! Only 29% of women artists had children under 18, almost six percentage points lower than for women workers in general. So like Cassatt, it appears that many contemporary women artists have decided to avoid the social institution of motherhood.

The incredible Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo, once said, “Painting completed my life.” I think my mother felt the same way, even though she never achieved traditional “success” as a painter…