by Mindy Fried | Nov 21, 2010 | child care, early education and care, family, parental leave policy, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, work statistics

Yesterday, I shared a long plane ride with a Japanese woman who was coming to the States to visit a friend. She patiently helped me try to track down an old Japanese friend via Google. Yes, there was WiFi on board; yes, Google in Japanese is very cool; and no, we were not successful in tracking her down! But more importantly, we talked about work and family issues, as she described the gendered division of labor in Japan. She is employed as a translator, but took a 10 year hiatus from her paid work – actually quit her job – to care for her son. This is typical, she said, among women “in her generation.” (After our conversation I calculated her age as around 43.)

In his book, The New Paradox for Japanese Women: Greater Choice, Greater inequality, Japanese economist Toshiaki Tachibanaki presents a gendered analysis of the Japanese economy. He reports that while Japanese women now have more choices in their careers than in earlier days when their education consisted of preparing them to be “good wives,” they now face job discrimination, sexual harassment and wage inequalities on the job. My new Japanese airplane friend commented that her husband wanted her to stay home with her son, telling her that it was the most important thing she could do. He, on the other hand, was working 12+ hour days. When I asked her if he was “able to” spend time “at home,” she winced and said that he did play with their son sometimes, but didn’t do any housework or cooking.

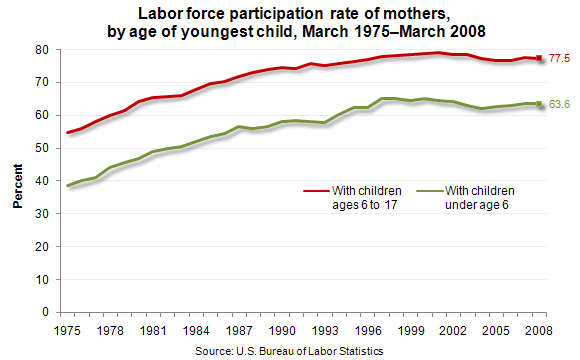

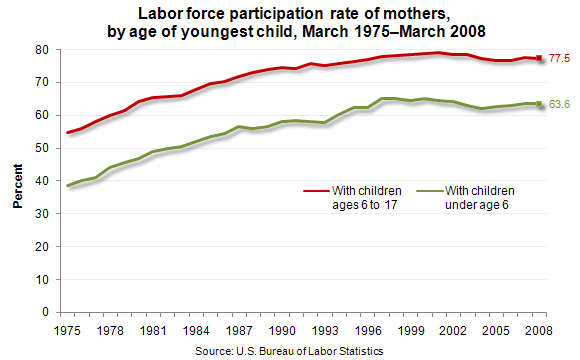

She was surprised to hear that over 75% of American mothers of school-age children work for pay. In Japan, nearly half of all women work in the labor force, but Japanese women earn less than half of what men earn. So it’s no surprise that women take on the brunt of the caregiving responsibilities, simply from an economic perspective. By the way, the gender wage gap in the US also is a significant problem, particularly for mothers, albeit less stark than in Japan.

She also described the dissolution of the extended family in which multiple generations lived together. Without a grandparent to do childcare, women in Japan have a harder time sustaining full time employment.

While we didn’t dive into a discussion of childcare policy in Japan, her observation got me thinking about the meaning of community and the gendered division of labor during my childhood years in the 50s. The 1950s in the U.S. are portrayed much like my Japanese friend’s description of contemporary Japanese culture, with the general assumption that mothers’ most important work was to stay at home with their children.

But what did staying at home actually mean in 1950s America? I know from personal experience, as a child of the 50s, I spent hours playing on the street with my friends. Whether it was kickball, dodgeball, relay or two-person races, or making up plays, we kept each other busy (on the street, as opposed to off the streets!). When I wasn’t in school or hanging out with my buddies on the street, I was taking dance classes or piano lessons. And when I wasn’t in school, on the street or at a lesson, I was firmly planted in front of our black-and-white TV, watching “traditional family life” in shows like Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best, and Ozzie and Harriet. While my mother was a “stay-at-home” mom, like the majority of middle-class mothers in that era, she and I didn’t spend a whole lot of time together because, frankly, I had other fish to fry!

Despite the glorification of family life in 1950s America, believe it or not, mothers today spend about the SAME amount of time as the 50s and 60s moms who did not work outside of the home! Family sociologist Suzanne Bianchi found that while the number of children with mothers in the paid labor force has gone up considerably between 1965 and 2000, there has actually been a slight INCREASE in the amount of time moms are spending with their children over these years now – from 10.6 hours per week in 1965 to 12.9 hours per week in 2000. Contemporary dads also spend a little more time with their kids these days, from 2.6 hours per week in 1965 to 6.5 hours per week in 2000.

So what’s the deal? Well it looks like a number of factors have converged to create this new reality, even though mothers and fathers spend a lot of time at their paid jobs. First of all, the work of the “at-home” mother has been greatly altered by technology and fast food. Meal preparation – especially when it comes from a takeout joint, comes out of a package, or pops out of the microwave oven – takes less time. Mothers are also spending less time cleaning the house, compared to a few decades ago. Dust bunnies prevail! And actually, fathers never spent a whole lot of time cleaning the house anyway, so no big change there.

But equally important, the notion of good parenting has shifted over the years from more hands-off to more intensive, involved parenting. From playing classical music to your in-utero fetus to knowing all your kids’ teachers to coaching her Little League team to texting daily with college age kids, the contemporary notion of “good parenting” has been redefined as engaged parenting. Based on the research, it seems that mothers who work outside the home want to “protect” the amount of time they have with their children; ergo, spend as much time with them as possible.

In her study of nurses who work night shifts, Anita Garey found these women chose night hours so they could maintain the notion of the “ideal mother” who was available to meet during the day with her child’s teachers, bake for the bake sales, and show up at school events. All this came at a cost: sleep and personal care. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild called this phenomenon the “time famine.” Bianchi argues that the increase of mothers in the paid labor force, at least in two-parent families, has shifted some of the caregiving responsibility to fathers, commenting,

“Perhaps most controversial, women’s reallocation of their time probably has changed men. The increase in women’s market work has facilitated the increase in women’s involvement in child-rearing, at least within marriage.”

Clearly, the economy is the driver in the U.S. and other parts of the world, creating an imperative for women to participate in the paid labor force. But women, like men, derive meaning from paid work, and the women’s movement of the 1970s – while rarely mentioned these days – had a powerful impact on women’s sense of entitlement in the workforce.

While we are not battling the level of tradition that exists within Japanese culture, we have a long way to go to achieve equity, particularly for mothers in the paid labor force.

To achieve real equity in the labor force, we need concrete changes in government policies that promote and protect wage equity for women, and protect against gender- and parent-based job discrimination. We need a paid parental leave policy, and support for shorter work hours so that parents of young children can choose to gradually return to full employment after taking a parental leave from the jobs. We need universal child care so that all young children have access to high-quality early education and care, and not just those in families that can afford it. And we need universal health care, so that workers are not reliant on a job for their health insurance. That’s too dangerous in this economic climate, and even with employer-based insurance, there is too much variability in the type of care provided.

Tall order? Maybe, but we need a comprehensive set of solutions to achieve “good parenting” in this age of work-family imbalance.

by Mindy Fried | Nov 2, 2010 | family, parenting, value of caregiving work

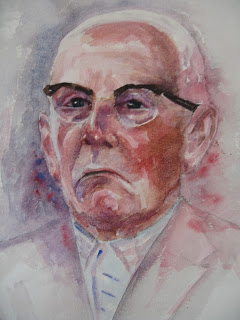

When I first visited my father’s assisted living facility, some guy shuffled up to me and asked, “Am I going to dinner or lunch?” I managed to reply as if it were the most normal question in the world, but felt like I had landed in the Twilight Zone. Over the past year, I’ve grown accustomed to hearing just about anything that anyone says. For example, over dinner this guy I really like, Harry, whispers to me in a conspiratorial tone, “How old is your father?” I tell him, for the umpteenth billion time, that he is 97-years-old. And as if this is the first time he’s heard this news, he responds with shock, telling me that my father looks so young! Harry tells me he’s 90 and then turns to his girlfriend, Millie, who is only 80, and says, “Isn’t that right?” She replies patiently, “Yes.”

Lately, I’ve been spending a lot of weekends with my father, as his health is rapidly declining. Despite the fact that he’s officially in home hospice, he is enjoying lunch and dinner visits with friends, and he goes to exercise class every day at the facility. On Sunday, he was too tired to go and as he was contemplating what to do, admitted that he felt guilty for not going. He’s not even Catholic!

I started looking forward to joining him at his morning weight exercise class, where a young and very perky teacher gets things rolling with balloon volleyball, a “game” I associate with young children. It’s pretty straightforward. She stands in the middle of the circle of residents who are all seated in their chairs or wheelchairs, and she flips the ball around the room, making sure everyone has a turn. Some are very cautious with the balloon; others give it a big whack and laugh out loud.

I’m amazed at how long folks enjoy playing this game. Even though the class is called weight exercise, this weightless balloon game constitutes about three quarters of the class. I get into it, mixing up my “moves” with actual hard punches and an occasional soccer head hit, which is entertaining for this crowd. Later in the dining hall, I see some of my volleyball team and we have a special connection.

For a moment, I imagine what it would be like if I actually lived here. And then I realize that by the time I had to live there, I probably would have some fairly significant things missing, like my ability to move freely and maybe even my mind.

Of course, all of this fun and games is punctuated by an undercurrent of failing health, as residents notice who is not showing up at bingo or as someone is rushed out of the building on a stretcher. Harry often asks me how my father is doing, calling him “Mack” even though that’s not his name. His girlfriend reminds him, with a touch of annoyance sprinkled with humor. He says to me hopefully, “Mack looks really good, just the same as when he first moved in, doesn’t he?” The fact is that “Mack” isn’t doing too well at all, but I don’t have the heart to tell Harry.

I feel grateful that we found a place where the staff are kind and mostly competent, and the residents aren’t all out-of-it. My father first moved in after a serious fall and it was evident that he could no longer live independently. He was willing to move, but angry just the same, and at times, said he had to get out of there. He felt alienated. These weren’t “his” people. He assumed they weren’t into what he was into, like theater, literature and politics. He certainly wasn’t a bingo kind of guy, either, which is one of the big pastimes in that place. But over the year, he has succumbed to “gambling”, as he calls it, and takes pleasure in being in the company of others. Happy hours – which include cocktails like Margaritas served in little paper cups- seem to tickle his fancy.

It’s harder for him to follow conversations, and there’s no point in bringing him to the theater now, because he is now legally blind, and anyway, he’d have trouble following the action and would end up sleeping through the whole thing. Not to mention that getting there and back would be very hard.

How do we want to live the “end-stage” of our lives? The research says that a critical factor that keeps people going – no surprise – is engagement in meaningful activities. Another important thing that keeps us alive is giving to others. The bottom line is that we all need to feel that our lives have meaning, that were contributing to society, more broadly, or to our friends and loved ones at a personal level. We all want a life well-lived.

But how do we maintain engagement? Perhaps we need to ask: What are we doing now in our lives that will sustain our sense of engagement? What kind of networks will we still have if and when we live long? How do we maintain a network of younger friends? Because chances are, all or most of our contemporaries will be gone if we live very long. And what about housing? My father lived on his own until he was in his mid-90s, resisting our efforts to consider safer options. We could never imagine him in an institutional setting, but we’re lucky that he can afford a decent assisted living facility and extra care, as needed. But what about the thousands of elders who don’t have the resources to live this end-stage of their lives surrounded, as he is, with dignity and love?

I leave my weekends with my father feeling exhausted but glad I was there with him. And I can’t help but wonder whether I’ll live to his age or older, and if I do, what kind of options will be available for the old woman I become.

by Mindy Fried | Oct 13, 2010 | child care, family, parental leave policy, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work

A sociologist buddy of mine just told me that she may be using my book on parental leave in a new class she’s teaching (Taking Time: Parental Leave Policy and Corporate Culture). While I should be overjoyed, I am not. Why? Because the book is 12 years old and it’s sadly as relevant today as it was twelve years ago!

Taking Time is based on an ethnographic study. In other words, I went native and hung out for a year in a financial services corporation I called Premium, Inc., studying its corporate culture. I wanted to understand how the culture of the workplace affected employees’ attitudes towards the company’s generous parental leave policy and ultimately, who used it.

I happened to be doing this study right after the passage of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA.), which was the first bill President Clinton signed in 1993. The bill mandates employers to allow their workers – women and men – to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to parent their newly arrived baby (biological or adoptive). This federal policy provided basic rights to Premium employees, in addition to the company’s own parental leave policy.

To my dismay, I found a strange and insidious blend of economics and culture that seriously undercut the use of parental leave policy at Premium. Of the 143 parental leave takers I interviewed, 140 were women and 3 were men! Women in high-level positions barely took leaves. In fact, only two female vice presidents took five weeks; the three senior female managers took five, nine and 10 weeks respectively. As one female senior manager said,

“Old-time management in the company still has an old mind-set about about women and work and family…The women who generally get to the higher top are the women who don’t have the children. You have to sacrifice something to get there.”

Not a single male senior manager took a parenting leave. Instead, new fathers tended to take 2-week vacations after the arrival of their new baby. One male manager I interviewed told me,

“It was simple economics. I was going to work full-time and (my wife) was going to work part-time. We joke about her job being a hobby because she’s hardly covering the cost of daycare.”

Most men facing new parenthood didn’t even consider taking time away from their jobs to parent a newly arrived infant, because they were worried their careers would suffer. For them, the cultural norms of the workplace mitigated against taking time to do what is still considered “women’s work”. Simply put, for both high-level female and male managers, babies and briefcases didn’t go together. This cultural norm trickled down to the organizational culture…

The largest group of workers who used the leave policy were women in non-management positions. Professional non-management women took an average of 10 weeks leave, two weeks less than the 12 weeks allowed by the FMLA! And nonprofessional women – women who earned less than those in professional positions – took an average of 8 weeks, with half taking 7 weeks or less. These women simply couldn’t afford to take longer leaves. Unless they had family lining up to care for their babies, much of their time was spent worrying about setting up quality, affordable childcare. This short leave-time falls far short of the six-month leave that T. Berry Brazelton, child development expert, recommends to support parent-child bonding.

In a 2009 study of current leave-taking practices, researchers found a a similar picture. There has been a very small increase in the amount of leave-time taken in the birth month (5.4%) by “highly educated and married mothers” and an increase of 13% in the next two months (Han, Ruhm and Waldfogel, 2009). Single mothers, on the other hand, are less able to afford unpaid leave. And fathers continue to take extremely short leaves or none at all.

This data confirms what I found in my study 12 years ago: that uppaid leave policy discriminates against those at the lower rungs of the income ladder who cannot afford to take longer leaves. With the absence of a mechanism to replace workers’ wages during the leave period, non-management female employees shorten their leaves; management employees take short leaves; and men don’t take parental leaves at all.

While lower paid workers would be the most obvious beneficiaries of paid leave, in fact, ALL employees would benefit from such a policy. The U.S. is the only wealthy nation in the world that does not offer parental leave, according to political scientist Janet Gornick, who conducted a cross- national study of parental leave policies.

“The United States has the least generous parental leave policies of all 21 economies compared in the study. We pay a high price for our meager policy, because parental leave improves the health and well-being of children and their parents, and paid leaves provide families with crucial economic support at such an important time.”

Gornick and her colleagues report that European countries, led by Finland, Norway and Sweden, rank far ahead of the United States in providing guaranteed parental leave, with Sweden ranking highest for gender equality and parental leave practices. Germany also offers a generous paid leave policy, and four countries show high levels of both generosity and gender equality: three Nordic countries (Finland, Norway and Sweden), and Greece.

We have a long way to go in the U.S.! California finally passed paid parental leave legislation in 2002, and the U.S. military even offers paid leave to its members. But a recent effort to extend paid leave to civilian employees got stuck in the Senate. And other initiatives to create paid leave through “baby unemployment insurance” – in which some small portion of the state unemployment insurance fund would go towards a paid leave fund – has hit a wall, given high employment rates.

Nonetheless, the issue will not go away for the thousands of mothers and fathers around this nation who want to spend more time with their babies.

It may seem counterintuitive to push for paid parental leave in this economic crisis, especially as people are being laid off from their jobs. You might argue that laid-off workers have more time to hang out with their kids anyway. And besides, why would employers want to add incentives for their existing labor force to take time away from the job? But those laid-off workers will return to the workforce when the economy improves, and those employers should care about creating humane work environments that don’t burn out their workers. And why shouldn’t we join the rest of the Western industrialized world in providing social policies that support mothers and fathers in the workplace?

Without a federal policy that provides the foundation of support for leavetaking, I fear that we will continue to see the patterns of leave-taking I found in my study twelve years ago. And that’s just not fair.

Meanwhile, my sociologist buddy asked if I could come to her class to talk about my book. I wish it were old news…

by Mindy Fried | Sep 30, 2010 | child care, depression, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work, women artists

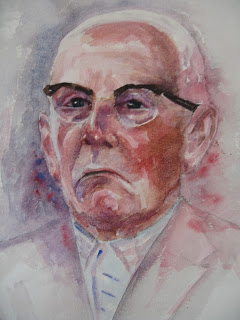

This is a picture of me and my mother. You’d never know from looking at the expression on her face that she hated being a “homemaker”. In fact, she looked pretty happy hanging out with me, even if we were washing dishes! In her younger years, prior to the birth of her two daughters, she wrote sultry torch songs and had her own radio show. Later, she studied painting and then continued to paint portraits until her final days. When I was a teenager, she exhibited her paintings every year in an outdoor art festival, near a studio she rented in what was considered the bohemian part of Buffalo, New York, my home town. Despite being an adolescent, this was the one and only weekend – every year – that I thought my mother was really cool.

Here is one of her watercolors that I still really love. Middle-class women of my mother’s generation – caught between the suffragettes of the early twentieth century and the second wave of the women’s movement of the 1970s – did not have an organized “sisterhood” of women supporting them to step out of the kitchen. As an artist, my mother was passionate about her work, but it was never considered a career, nor did it generate much income, even though she taught painting and sold commissioned portraits. In fact, in her era of young motherhood – the 40s and 50s – single middle-class women who worked for pay were expected to leave their jobs once they were married. As we know now, the independence of women is often tied to their earning capacity, and not being considered a professional was hard on her. This phenomenon was eventually coined the “problem without a name” by Betty Friedan.

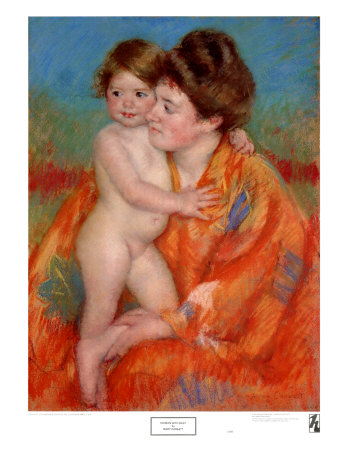

My mother’s favorite artist, Mary Cassatt, is quoted as saying:

“There’s only one thing in life for a woman; it’s to be a mother…A woman artist must be…capable of making primary sacrifices.”

How ironic, given that Cassatt never married, nor did she have children; and for many years she painted portraits of mothers and children!

Reflecting the schizophrenic existence of a strong-willed woman of that era, Cassatt also said,

“I am independent! I can live alone and I love to work!”

Even though her family objected to her becoming a professional artist, Cassatt began studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia – where my mother also studied art for one year. I never spoke to my mother about why she left, but Cassatt also left after one year, complaining that “there was no teaching” at the Academy. Unlike male students, females couldn’t use live models. This is likely just one of the inequities she encountered there. When she left, Cassatt moved to Paris. When my mother left, she moved back to Buffalo, New York…

My mother’s life was one of sacrifices, like so many women of her generation. The arts were a place for talented and creative women for whom other professional careers were closed. Maybe it was a vestige of the Victorian era when it was considered proper for upper-class girls and women to “dabble” in the arts. To be considered a serious artist was another thing though. And my mother always struggled to be considered a professional. It irked her when the realists or even the abstract expressionists – always male – won the competitions she entered. She intuitively understood that there was gender bias, but the proof was invisible. To be an artist means expressing oneself – putting one’s vision into the universe to challenge and inspire or simply to portray beauty. In an era where women’s voices were not heard, being a woman artist was revolutionary.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

In 1971, art historian Linda Nochlin published an article called “Why are there no great women artists?”, in which she identified a number of institutional barriers that explain why women artists had historically been on the periphery and not considered real artists. For example, in the 19th century, women couldn’t join the the painters guild; they were barred from official art schools; and they were not allowed to attend nude drawing classes.

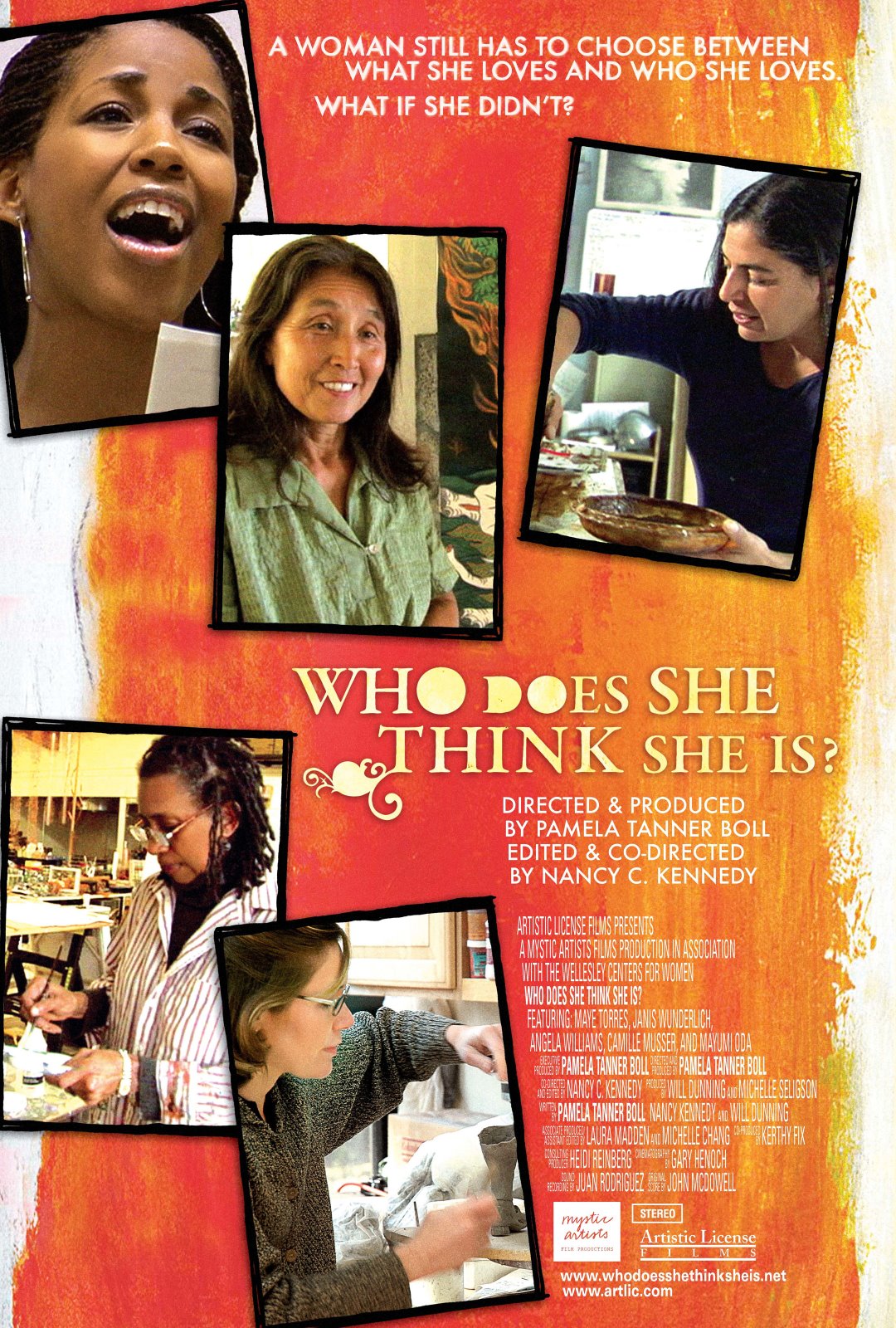

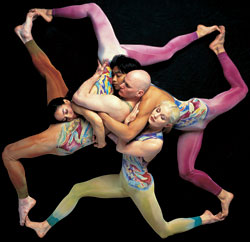

In a film about women artists called “Who does she think she is? – produced by Pamela Tanner Boll (who also produced Born into Brothels) – artists reflect on the challenges they face balancing their work and family demands.

They talk about how they’re not taken seriously precisely because they’re women. In fact, while 80% of students in visual arts schools are women, “in the real world,” 70-80% of artists whose works are shown in galleries and museums are male.

In an article in the New York Times, Marci Alboher says these statistics “sound alarmingly like the numbers released by organizations that track the presence of women in the highest echelons of professions like law, journalism, engineering or finance.” The women artists in the film also argue that they are dissuaded from focusing their art on the subject of mothers and children, because it is not considered “real” material. Both artist and subject are devalued…

Outside the art world, says Alboher, people rarely discuss the challenges faced by women artists “moving up the ranks.” This has a lot to do with the fact that women are still considered primary caregivers in this society. Despite the large percentage of mothers in the labor force, we are still defined primarily by our capacity to bear children. Most workplaces do not accommodate the need for work-life balance for their employees, be they women or men.

As a teenager, I was often frustrated by my mother’s lack of confidence in her work. I wanted her to be a strong role model in many ways, someone who followed her passion and knew she had talent as an artist. But now I have an increased understanding of the effects of working in isolation, in a society that didn’t value the work of women artists, and in the microcosm of that society, in a family that expected her to have dinner on the table every night. (No wonder she hated to cook!)

I love the comment by Georgia O’Keefe who once said,

“I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking the time to look at it. I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

It takes guts to think that your painting will stop New Yorkers in their tracks! But while guts are good, women’s voices need to be valued; the balance of caregiving must be shared; workplaces need to accommodate the work-life balance needs of parents; and social policy must broaden to include paid parental leave and universal, free early care and education.

According to a 2008 National Endowment for the Arts report called “Artists in the Workforce: 1990-2005”, women artists are as likely to marry as women workers in general, but… they are less likely to have children! Only 29% of women artists had children under 18, almost six percentage points lower than for women workers in general. So like Cassatt, it appears that many contemporary women artists have decided to avoid the social institution of motherhood.

The incredible Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo, once said, “Painting completed my life.” I think my mother felt the same way, even though she never achieved traditional “success” as a painter…

by Mindy Fried | Sep 14, 2010 | family, parenting, policy, value of caregiving work, women and work

Like many daughters and sons, I am a caregiver from afar, talking to my father on a daily basis, sometimes two to three times a day, consulting with nurses and doctors, and managing a cavalcade of dedicated caregivers who do “my” job by proxy. I supervise the caregivers, support them and problem solve with them. They are my eyes and ears and I am ever grateful for their insights. I’m very lucky to share this job with my sister, who takes on a lion’s share of caregiving work, and with whom I can laugh, grumble and cry when needed. We are far from alone as distance caregivers…

The elderly population in the U.S. is expected to more than double between now and 2050, according to Boston College’s Center for Work & Family. Thousands of adult children take care of their parents. Not surprisingly, given the gender division of labor in families, about two thirds of these caregivers are daughters. On average we are about 50 years old, and the recipients of our care are on average about 77 years old. My father is a lot older than that. In fact he’s almost 100! I truly hope I inherited his cat-has-nine-lives genes, but we shall see…

Of all the adults who care for an elder parent, a little over 10% do it like us, from afar. My sister and I tried to get our dad to come live in either of our cities, but he is rooted in his own hometown. It is there that he has established his identity and is surrounded by a flock of loved ones, including people who admire him for his past accomplishments.

There’s no doubt that caring for an elder parent requires a team effort. It’s hard to imagine how some people do it, or sometimes even how we do it! The older our father gets, the more we have hunkered down to the task of trying to keep him healthy and engaged, and to help him remember who he is and has been in his life. And yet ultimately, there is a limit to how much power or influence we – his loved ones, friends and paid caregivers – actually have.

Nearly 60% of those who care for their elder parents are in the paid workforce, and the majority of us work full-time. Our work as caregivers is on top of – and sometimes in the midst of – our paid work. It’s not uncommon for me to get a call in the middle of my workday either from my father or about my father, and whatever work is generated from the call simply gets woven into the many strands of my other responsibilities. I’m lucky that as a consultant who makes her own hours — working odd times and places — I have the workplace flexibility that allows this weaving process.

An increasing number of employees need flexibility in their paid work schedules to accommodate the responsibilities they have as unpaid caregivers. They may need to drive elder parents to appointments, and those of us who provide care from a distance may need to find other people to do the driving. Whether near or far, we often make those appointments, monitor medications, buy necessities, ensure that their housing is safe, their meals nutritious, and their friends aware of what’s going on. We often need to fight to ensure that the care of our parents is high-quality and consistent. More than 54% of caregivers have advocated for their “care recipient” with providers of services and government agencies, according to the National Alliance of Caregiving.

In a report by the Center for Boston College Center for Work & Family, researchers say:

“It is surprising that employers are not moving faster to address elder care issues in the workplace. Why? Many employers just don’t know what to do, or have difficulty grasping the extent to which elder care is an issue for their employees.”

Researchers found that workers often opt not to discuss their caregiving problems with coworkers or supervisors, “a silence reinforced by our society’s reluctance to confront issues of aging and death.”

They also note that the business impact of not responding to employees’ caregiving responsibilities is significant, and includes work interruptions (e.g, unexpected time off, tardiness) which may affect worker productivity; caregiver stress and fatigue that can result in higher medical and employee assistance costs; and potential turnover when employees simply cannot balance caregiving and work demands. In fact, according to a 1995 study by Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, elder care costs a company about $3,142 a year per employee, based on various costs associated with employee productivity.

In a 2009 study by the Sloan Center on Aging & Work at Boston College, researchers found,

“Over 78% of respondents reported (that) having access to flexible work options contributes to their success as employees to a moderate or greater extent (and) 90% reported that (these) options contribute to their overall quality of life to a moderate or great extent.”

Flextime, compressed work hours and telecommuting are just some of the alternative scheduling options that can help workers with their caregiving demands. While there are some “family-friendly” companies that recognize the personal needs of their workforce, there’s still a long way to go. In a study I did on flexible work policies in five large corporations, I found that unless companies had a written work policy that all employees were aware of, employees found it difficult to negotiate an arrangement with their supervisors.

Interestingly, according to the National alliance for Caregiving, from 2004 to 2009, there has been a notable increase in the percentage of caregivers who live within 20 minutes from their elder parents – from 44% to 51%. Regardless of where we live, our elder parents need us. And as caregivers, we need support — from our family and our workplaces — to be there for them.

Finally what can government do? Right now we have an inadequate law – the Family and Medical Leave Act – that provides unpaid leave to employees who take time off from work to care for a sick family member. Making that policy a paid leave would be a good start…

by Mindy Fried | Aug 30, 2010 | child care, parenting, value of caregiving work, women and work

I have to admit that I’m a sap for human interest stories in the news. And lately, this dominates what we are fed by the media. I’m even a sucker for the obituaries, which can provide fascinating portraits of people’s lives. The story that grabbed me this morning was the one about former tennis champ, Gigi Fernandez, and her quest to have children (http://tiny.cc/hak4h). Never mind that I’d never heard of her (apologies to any Gigi fans!).

With a title like “A Dream Deferred: Almost Too Long”, I was hooked. Spring forward (to the middle of the story) where she and her female partner now have toddler twins, thanks to a friend who donated eggs and an anonymous sperm donor. (By the way, kudos to the New York Times for not making a big deal that they are a same-sex couple.) When Gigi’s friend asked her, “What do you need to have a baby?”, she replied “eggs”. Love that line. Wish some of my friends would ask me what I need to get exactly what I want, and then say, no problem, I have some and you can have them. (I could use a new car, for anyone who is reading this.)

Gigi struggled to get pregnant. She was over 35, which believe it or not puts a woman in the “high risk” category. I know this from personal experience, even though I did not encounter the same problems as Gigi. In addition to her age, according to her doctor, Gigi’s “Hall of Fame career” contributed to her inability to conceive. After seven infertility treatments, her doctor told her that her eggs were old. Ewww… Now there’s an image – and it must have stung. Like many athletes, GiGi’s career was dependent on her physical strength and agility, and her body let her down. She is quoted in the article as saying, “As an athlete, you have this attitude. I can do anything with my body… That’s how you think. So your biological clock is ticking, but you’re in denial.”

Gigi soaked up our society’s cultural imperative about the value of motherhood, as reflected in her insightful comment: “There is this implication that women are here to bear children, and if you can’t bear children, you’re useless.” Actually, 18% of US women in the U.S. do not have children, a figure that is gradually rising.

In Europe, it appears that the percentages of women who do not have children are higher. In Germany and Austria, one third of women in their 40s do not have children.

Meanwhile, Gigi persevered and got what she wanted: healthy twins. She says that after a career of being very selfish, she is now selfless. One might conclude that this means she no longer works for pay. But in fact, she has figured out a way to balance the care of her twins with her work teaching tennis and running a business. Of course, she has the advantage of financial success that makes a lot of this possible.

According to U.S. Census data, there are at least 270,000 children being raised by same-sex couples. But this does not include single LGB parents or transgender parents, and it is likely that same-sex parents are under-reported by the Census.

I’m glad that of all the puff pieces I see in the news, the New York Times chose to write about a lesbian in a same-sex relationship who opened herself to an alternative form of creating a family, and succeeded.