Yesterday, I shared a long plane ride with a Japanese woman who was coming to the States to visit a friend. She patiently helped me try to track down an old Japanese friend via Google. Yes, there was WiFi on board; yes, Google in Japanese is very cool; and no, we were not successful in tracking her down! But more importantly, we talked about work and family issues, as she described the gendered division of labor in Japan. She is employed as a translator, but took a 10 year hiatus from her paid work – actually quit her job – to care for her son. This is typical, she said, among women “in her generation.” (After our conversation I calculated her age as around 43.)

In his book, The New Paradox for Japanese Women: Greater Choice, Greater inequality, Japanese economist Toshiaki Tachibanaki presents a gendered analysis of the Japanese economy. He reports that while Japanese women now have more choices in their careers than in earlier days when their education consisted of preparing them to be “good wives,” they now face job discrimination, sexual harassment and wage inequalities on the job. My new Japanese airplane friend commented that her husband wanted her to stay home with her son, telling her that it was the most important thing she could do. He, on the other hand, was working 12+ hour days. When I asked her if he was “able to” spend time “at home,” she winced and said that he did play with their son sometimes, but didn’t do any housework or cooking.

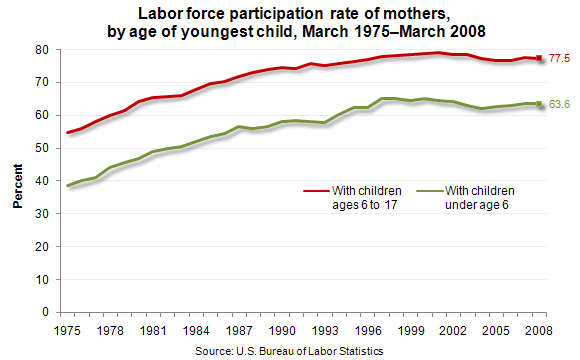

She was surprised to hear that over 75% of American mothers of school-age children work for pay. In Japan, nearly half of all women work in the labor force, but Japanese women earn less than half of what men earn. So it’s no surprise that women take on the brunt of the caregiving responsibilities, simply from an economic perspective. By the way, the gender wage gap in the US also is a significant problem, particularly for mothers, albeit less stark than in Japan.

She also described the dissolution of the extended family in which multiple generations lived together. Without a grandparent to do childcare, women in Japan have a harder time sustaining full time employment.

While we didn’t dive into a discussion of childcare policy in Japan, her observation got me thinking about the meaning of community and the gendered division of labor during my childhood years in the 50s. The 1950s in the U.S. are portrayed much like my Japanese friend’s description of contemporary Japanese culture, with the general assumption that mothers’ most important work was to stay at home with their children.

But what did staying at home actually mean in 1950s America? I know from personal experience, as a child of the 50s, I spent hours playing on the street with my friends. Whether it was kickball, dodgeball, relay or two-person races, or making up plays, we kept each other busy (on the street, as opposed to off the streets!). When I wasn’t in school or hanging out with my buddies on the street, I was taking dance classes or piano lessons. And when I wasn’t in school, on the street or at a lesson, I was firmly planted in front of our black-and-white TV, watching “traditional family life” in shows like Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best, and Ozzie and Harriet. While my mother was a “stay-at-home” mom, like the majority of middle-class mothers in that era, she and I didn’t spend a whole lot of time together because, frankly, I had other fish to fry!

Despite the glorification of family life in 1950s America, believe it or not, mothers today spend about the SAME amount of time as the 50s and 60s moms who did not work outside of the home! Family sociologist Suzanne Bianchi found that while the number of children with mothers in the paid labor force has gone up considerably between 1965 and 2000, there has actually been a slight INCREASE in the amount of time moms are spending with their children over these years now – from 10.6 hours per week in 1965 to 12.9 hours per week in 2000. Contemporary dads also spend a little more time with their kids these days, from 2.6 hours per week in 1965 to 6.5 hours per week in 2000.

So what’s the deal? Well it looks like a number of factors have converged to create this new reality, even though mothers and fathers spend a lot of time at their paid jobs. First of all, the work of the “at-home” mother has been greatly altered by technology and fast food. Meal preparation – especially when it comes from a takeout joint, comes out of a package, or pops out of the microwave oven – takes less time. Mothers are also spending less time cleaning the house, compared to a few decades ago. Dust bunnies prevail! And actually, fathers never spent a whole lot of time cleaning the house anyway, so no big change there.

But equally important, the notion of good parenting has shifted over the years from more hands-off to more intensive, involved parenting. From playing classical music to your in-utero fetus to knowing all your kids’ teachers to coaching her Little League team to texting daily with college age kids, the contemporary notion of “good parenting” has been redefined as engaged parenting. Based on the research, it seems that mothers who work outside the home want to “protect” the amount of time they have with their children; ergo, spend as much time with them as possible.

In her study of nurses who work night shifts, Anita Garey found these women chose night hours so they could maintain the notion of the “ideal mother” who was available to meet during the day with her child’s teachers, bake for the bake sales, and show up at school events. All this came at a cost: sleep and personal care. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild called this phenomenon the “time famine.” Bianchi argues that the increase of mothers in the paid labor force, at least in two-parent families, has shifted some of the caregiving responsibility to fathers, commenting,

“Perhaps most controversial, women’s reallocation of their time probably has changed men. The increase in women’s market work has facilitated the increase in women’s involvement in child-rearing, at least within marriage.”

Clearly, the economy is the driver in the U.S. and other parts of the world, creating an imperative for women to participate in the paid labor force. But women, like men, derive meaning from paid work, and the women’s movement of the 1970s – while rarely mentioned these days – had a powerful impact on women’s sense of entitlement in the workforce.

While we are not battling the level of tradition that exists within Japanese culture, we have a long way to go to achieve equity, particularly for mothers in the paid labor force.

To achieve real equity in the labor force, we need concrete changes in government policies that promote and protect wage equity for women, and protect against gender- and parent-based job discrimination. We need a paid parental leave policy, and support for shorter work hours so that parents of young children can choose to gradually return to full employment after taking a parental leave from the jobs. We need universal child care so that all young children have access to high-quality early education and care, and not just those in families that can afford it. And we need universal health care, so that workers are not reliant on a job for their health insurance. That’s too dangerous in this economic climate, and even with employer-based insurance, there is too much variability in the type of care provided.

Tall order? Maybe, but we need a comprehensive set of solutions to achieve “good parenting” in this age of work-family imbalance.

Mindy, great article. My daughter lived in Japan for ten (1) years, and is now a stay-at-home mom but with lots of interests and skills. She is starting an internet business that she can run from home. The internet opens up a whole new world of opportunities for stay-at-home moms or dads allowing them to be highly productive, revenue producing and more quality time with their children. Gary

Thanks, Gary. Good point about the potential for running a biz on the internet for moms/dads!

Great blog! As always, interesting, well written, and informative. Lor

Great post Mindy! More material for my Family course. In some ways it reminds me of arguments I hear for stay at home moms in Pakistan – which overlook completley that most stay at home moms (anyone who is in the middle class or above)have full-time nannies at home to take care of their children, just as working mothers do!

Really interesting, Afshan…

Great great post – I love how you've integrated research here.

That family picture with Dad as the center of an adoring universe is sickening.

Shared your post with http://www.playwatch.org (another listserv I'm on!), with the comment:

I think the cultural pressure to "helicopter parent" has many sources, but I wonder if one of them is payback for Moms' workforce participation.

Thanks for re-posting, Jess. It's great to have your comments!

Really interesting article. I too have thought about some of these questions as the statistics don't tell the full story of what the struggles, challenges and choices women content with when they are trying to work outside the home.

Perhaps employers can learn from these articles too.

Thanks, Lori!

Many European countries have adopted the kinds of policies Mindy describes, designed as protections against what they call "new social risks." The latter relate to women's increased presence in the paid workforce and the resulting need to redistribute the responsibility for family care that was once theirs alone.

By contrast, “old social risks" had to do with protecting the male breadwinner, who in turn was expected to provide for his family. So in the mid-20th century, many industrialized countries, including the US, adopted policies such as Social Security (including disability and survivor benefits) along with unemployment and health insurance–all of which seem normal, necessary, and unremarkable to us now.

It won't be easy to institute new pro-family policies in the conservative business climate that is the US, but it helps to be able to name what we need and talk about it, and in talking about it to make it more normal and less radical. Thanks to Mindy for her contributions to the conversation. And while we're about it, we can't neglect to defend and extend the protections we already have, Social Security and Medicare chief among them. Their survival can't be taken for granted.

Thanks to "Anonymous" for your astute comment about our need for progressive social policies (that most other European countries already have) in our current conservative climate. Glad we're keeping the conversation alive!