by Mindy Fried | Sep 14, 2010 | family, parenting, policy, value of caregiving work, women and work

Like many daughters and sons, I am a caregiver from afar, talking to my father on a daily basis, sometimes two to three times a day, consulting with nurses and doctors, and managing a cavalcade of dedicated caregivers who do “my” job by proxy. I supervise the caregivers, support them and problem solve with them. They are my eyes and ears and I am ever grateful for their insights. I’m very lucky to share this job with my sister, who takes on a lion’s share of caregiving work, and with whom I can laugh, grumble and cry when needed. We are far from alone as distance caregivers…

The elderly population in the U.S. is expected to more than double between now and 2050, according to Boston College’s Center for Work & Family. Thousands of adult children take care of their parents. Not surprisingly, given the gender division of labor in families, about two thirds of these caregivers are daughters. On average we are about 50 years old, and the recipients of our care are on average about 77 years old. My father is a lot older than that. In fact he’s almost 100! I truly hope I inherited his cat-has-nine-lives genes, but we shall see…

Of all the adults who care for an elder parent, a little over 10% do it like us, from afar. My sister and I tried to get our dad to come live in either of our cities, but he is rooted in his own hometown. It is there that he has established his identity and is surrounded by a flock of loved ones, including people who admire him for his past accomplishments.

There’s no doubt that caring for an elder parent requires a team effort. It’s hard to imagine how some people do it, or sometimes even how we do it! The older our father gets, the more we have hunkered down to the task of trying to keep him healthy and engaged, and to help him remember who he is and has been in his life. And yet ultimately, there is a limit to how much power or influence we – his loved ones, friends and paid caregivers – actually have.

Nearly 60% of those who care for their elder parents are in the paid workforce, and the majority of us work full-time. Our work as caregivers is on top of – and sometimes in the midst of – our paid work. It’s not uncommon for me to get a call in the middle of my workday either from my father or about my father, and whatever work is generated from the call simply gets woven into the many strands of my other responsibilities. I’m lucky that as a consultant who makes her own hours — working odd times and places — I have the workplace flexibility that allows this weaving process.

An increasing number of employees need flexibility in their paid work schedules to accommodate the responsibilities they have as unpaid caregivers. They may need to drive elder parents to appointments, and those of us who provide care from a distance may need to find other people to do the driving. Whether near or far, we often make those appointments, monitor medications, buy necessities, ensure that their housing is safe, their meals nutritious, and their friends aware of what’s going on. We often need to fight to ensure that the care of our parents is high-quality and consistent. More than 54% of caregivers have advocated for their “care recipient” with providers of services and government agencies, according to the National Alliance of Caregiving.

In a report by the Center for Boston College Center for Work & Family, researchers say:

“It is surprising that employers are not moving faster to address elder care issues in the workplace. Why? Many employers just don’t know what to do, or have difficulty grasping the extent to which elder care is an issue for their employees.”

Researchers found that workers often opt not to discuss their caregiving problems with coworkers or supervisors, “a silence reinforced by our society’s reluctance to confront issues of aging and death.”

They also note that the business impact of not responding to employees’ caregiving responsibilities is significant, and includes work interruptions (e.g, unexpected time off, tardiness) which may affect worker productivity; caregiver stress and fatigue that can result in higher medical and employee assistance costs; and potential turnover when employees simply cannot balance caregiving and work demands. In fact, according to a 1995 study by Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, elder care costs a company about $3,142 a year per employee, based on various costs associated with employee productivity.

In a 2009 study by the Sloan Center on Aging & Work at Boston College, researchers found,

“Over 78% of respondents reported (that) having access to flexible work options contributes to their success as employees to a moderate or greater extent (and) 90% reported that (these) options contribute to their overall quality of life to a moderate or great extent.”

Flextime, compressed work hours and telecommuting are just some of the alternative scheduling options that can help workers with their caregiving demands. While there are some “family-friendly” companies that recognize the personal needs of their workforce, there’s still a long way to go. In a study I did on flexible work policies in five large corporations, I found that unless companies had a written work policy that all employees were aware of, employees found it difficult to negotiate an arrangement with their supervisors.

Interestingly, according to the National alliance for Caregiving, from 2004 to 2009, there has been a notable increase in the percentage of caregivers who live within 20 minutes from their elder parents – from 44% to 51%. Regardless of where we live, our elder parents need us. And as caregivers, we need support — from our family and our workplaces — to be there for them.

Finally what can government do? Right now we have an inadequate law – the Family and Medical Leave Act – that provides unpaid leave to employees who take time off from work to care for a sick family member. Making that policy a paid leave would be a good start…

by Mindy Fried | Aug 16, 2010 | family, immigrants, Jewish history, memories, women and work

There is a rising anti-immigrant tide in this country that frightens me. It feeds on our depressed economy and is fueled by pervasive prejudices against people of color. The anti-immigrant law in Arizona epitomizes its ugly face, and elements of the right wing in this country are embracing the opportunity to assert a narcissistic frame on who is a “real American”.

What would my grandmother say?

Even though this country was founded by immigrants and shaped by the immigrant ethos — the notion of a safe haven — our history is also replete with contradictions, as manifested in the darker side of our past, namely Native American genocide and slavery. Let’s also not forget that even when slavery was abolished, women were second-class citizens in this nation.

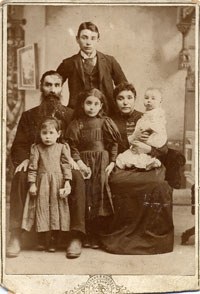

When I think of our nation’s history, I think about my own grandmother. She came on her own to this country from Hungary around 1890, traveling on a ship in a wave of Eastern European Jews who were looking for a better life on these shores. The details of her trip are a little fuzzy because she didn’t like to talk about “the past”. She even yelled at my grandfather one time when he started to tell me about his childhood in Hungary. “Saul! She doesn’t want to hear what happened so long ago!”, she snapped at him in her thick Eastern European accent, a comment I regret to this day.

We do know that my grandmother was only 13 years old when she arrived and like so many before and after her, she came through Ellis Island. She lived for a time in Manhattan with relatives who made the same journey. At some point, she got back on a boat and returned to Hungary, to bring her parents back with her. I imagine that by this point, she was fluent in English and that they spoke none. They lived in New York City, and through her teen years she became a skilled seamstress, working in sweatshops by day and studying clothing patterns by night so she could master the skill. She and my grandfather met in New York, where they opened a “dry goods” store, which apparently is a store that sells just about anything. She had, by then, become a master seamstress, and was also a mother of nine children, all of whom attended public schools and ultimately “made good”, achieving the American dream of sorts.

Of her nine children, there was one dentist, two English professors (including my father), a factory owner, an accountant, an architect, a schoolteacher, a bookkeeper and a postal worker. All but one had children of their own, 21 in all, and these children had over 20 children, and on and on it goes. With each successive generation, they are one step away from their heritage, and yet most have tried — in their own ways — to maintain a connection to their history.

How many people in America have some version of this story? Either they came to this country from foreign soil or the parents came or their grandparents came, to create a better life for themselves. They may have been fleeing political persecution or poverty or both. And when they came here, they struggled to learn the language, gain new skills, find jobs, and live the American dream. When they got to this country, they worked very, very hard. Many experienced discrimination, often from people who felt threatened by them in some way or wanted someone to be lower on the totem pole than them.

As Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, my grandparents were Caucasian. So while they experienced discrimination as Jews and as poor people, they didn’t experience discrimination because of the color of their skin.

When I hear about the anti-immigrant “movement”, I honestly feel sick. That must have something to do with my grandmother, as I think: Who are these people who hate people who are just arriving? Who are these people who want to close the borders? Who are these people who want to pass laws that allow English only? Who are these people who want to deny a college education to children of immigrants?

And what would their grandmothers say?