by Mindy Fried | Jun 10, 2016 | aging, connections with people, engaged aging, family, feminism, gender, health care, House Un-American Activities Committee, making choices, resiliency, theatre, Uncategorized, work and family balance

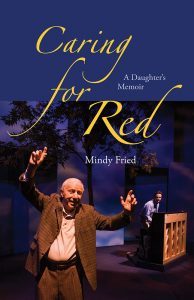

In this interview, Gayle Sulik, Founder of the Breast Cancer Consortium and Co-Founder of Feminist Reflections, talks with Mindy about her new book, Caring for Red: A Daughter’s Memoir (Vanderbilt University Press, forthcoming, Summer, 2016).

GAYLE: Mindy Fried, your new book Caring for Red tells a story of you and your sister taking care of your 97-old father in the last year of his life in an assisted living facility. Before we talk about your experience caring for your dad, Manny, tell me a little about him. Who was this colorful character? After all, he earned the nickname “Red.” Sounds fiery to me!

GAYLE: Mindy Fried, your new book Caring for Red tells a story of you and your sister taking care of your 97-old father in the last year of his life in an assisted living facility. Before we talk about your experience caring for your dad, Manny, tell me a little about him. Who was this colorful character? After all, he earned the nickname “Red.” Sounds fiery to me!

MINDY: My father was a person with many lives. As a young man, he was a labor organizer for the United Electrical Workers union where he organized factory workers. That was when industrial labor was still predominantly based in the US, and not in third world countries where labor is cheaper. At some point, he joined the Communist Party. I’m not sure how active he was or for how long, but certainly at that time, being considered a “Communist” was tantamount to being a terrorist in our current political climate. In1954, when I was around 4 years old, he was subpoenaed to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), a very traumatic experience for him, and for my whole family. He was “blacklisted”, meaning that when he applied for jobs, he was turned away. Eventually, he was hired by a Canadian company where he sold life insurance for around 15 years. That’s the kind of work he did through much of my childhood. But he was also writing plays based on his experience as a labor organizer, and he returned to the theatre as an actor, something he had done years before. When I was a teenager in the 1960s, he was subpoenaed by HUAC again. That was tough, but times had changed quite a bit and the ramifications weren’t quite as dire as they were the first time around. He ended up going back to school when he was in his 50s. Really impressive, since he had only one year of college under his belt. He went straight from finishing an undergraduate degree to working on a Ph.D. in English. His final career was as an English professor at SUNY Buffalo State College. You might say that nothing kept this guy down. He was a great role model in that sense.

GAYLE: How did your family survive the impact of the McCarthy period?

MINDY: I grew up with two people who were angry with each other often, but it was quiet anger. That was hard. I was lucky to have a best friend who moved in down the street from me when I was 5 years old, and her family basically adopted me. She liked my house because it was quiet, and I liked hers because it was lively and warm and loving. She became my “non-bio” sister, as we say; we’re still close today. Her parents became surrogate parents, and I am ever-grateful for that. They were just very attentive; my parents were often distracted. It was great to have another family a few doors down the street. That was one way I coped. But as a family, we also believed that my father made the right choices, in how he challenged HUAC, and continued to stand up for his beliefs. Having a sense of doing the right thing goes a long way.

GAYLE: Another name associated with Manny Fried, is “Morrie.” Six years before your father died, he played the character MORRIE in a play called Tuesdays with Morrie. As the story goes, a University graduate visits his former mentor, a sociologist who is slowly dying of a progressive disease. You write that your father inhabited that role fully, and that it helped to bring you closer together. Tell me why.

Well first of all, it was a big deal to play Morrie, not only because it was a great opportunity for my father, but also because he got to perform at the Studio Arena Theater, which had blacklisted him for many years. For me, the other exciting thing about him getting this role was that Morrie was a sociologist in my own department at Brandeis University. I knew Morrie, and the moment that my dad got the part, I saw it as an opportunity for the two of us to connect around his preparation and performance. I introduced him to Gordie Fellman, one of Morrie’s closest friends and colleagues from Brandeis. And I introduced him to a couple of Buddhists and sociologists who called themselves “Monday’s with Morrie”, as opposed to Tuesdays with Morrie (upon which the book and play were based). We also watched the Frontline TV series that Ted Koppel produced about Morrie, where Koppel interviewed him over the period of time as he was dying of ALS. When my dad came to visit me, he would have these meetings, and he would run his lines with me, and he would practice a grapevine dance from the play in my narrow hallway. It was just this really sweet thing that we connected around, and then obviously I always went to see him when he acted, so it was great to see him in the play, and he really did a beautiful job. People are always kind of amazed when they see old people function in any way, but seeing him excel at inhabiting this character – I think it was a really powerful experience for the audience and he pulled it off; he did a great job.

GAYLE: In your book, you describe a father who was loving – someone you felt deeply close with – but also a man who was full of himself. Did you feel resentment about taking care of him in this last year of his life?

MINDY: Well I think that this a really important question because as adult children, many of us have mixed feelings about our parents. The answer is “no”, I didn’t resent him. But it took me many years to understand him, to find equal footing with him, to find my voice with him, since he was a forceful speaker, sometimes controlling, and sometimes discounting of opinions that differed from his. He once told me that if I wasn’t sure about something, just guess, and that 99% of the time I’d be right. I was in my 30s when he gave me this advice, and by then I had his “number” and realized that this was sort of ridiculous. But he actually believed he was right most of the time! That said, I had deep respect for him and for his values and choices in life. He centered my world, for many years. In “exchange theory”, as it applies to families and relationships, the notion is that parents care for their children in one period of time, and later in life, when elder parents need support, children care for their parents. When it came time to care for my father, I did it with all my heart.

GAYLE: How did the father-daughter relationship change as Manny aged?

MINDY: My father and I were very close. Like most people, he was a flawed human being. He made serious choices in his life that impacted our family. But I had a deep respect for him, and we had a lot in common politically. For me, being part of the Women’s Movement in the 70s helped me better understand that despite being a good guy who was committed to social justice, he was pretty “old school”. I got frustrated with what a poor listener he was, and how I often had to fight for “air time” in conversations with him. But I did learn how to argue and debate because of him. I believe he felt I could be anyone or anything I wanted to be. And while he wasn’t comfortable “having or expressing feelings”, he was emotionally raw much of his life. That was one effect of McCarthyism on his life, and I understood that about him. Over the years, I understood enough of who he was to accept his shortcomings and his vulnerabilities and to just kind of let it go and say, “ok, here’s this person in the last bit of his life,” and to really be as fully present for him without losing myself.

GAYLE: You chronicle in your book many attempts, successful and unsuccessful, to find a place for your father to live that would meet his growing care needs AND offer the kind of life that fulfilled him. This was not easy, and sometimes your father was less than helpful. Tell me what worked, and what didn’t?

MINDY: I think one thing that worked was that I put myself in his shoes. For example, when we went and visited this super groovy retirement community that was connected to a college and he said to me, “there is absolutely no way I am going to move in there”. I imagined myself living with people that we met with, and I thought “I couldn’t do that either, this would be kind of horrible”. Not that they were bad people; it just felt foreign. These weren’t people he would choose to be friends with. I think that probably the most important thing as somebody gets older is to respect where they’re coming from. And I think it’s important to start thinking about these issues early on because you know, if you are trying to make a decision when it’s dire, the whole process of decision making is much more rife with emotion. I believe that talking about these things before you are in a crisis really makes a huge difference. And that helped us a lot.

GAYLE: Your father lived in Assisted Living for the final year of his life. Am I correct?

MINDY: Even though the book uses a one-year time frame, it was actually a year and a half that my sister and I cared for our father. It worked really well, until it didn’t. We learned what assisted living was able to provide for him as well as its limitations. Ultimately, in the last few months, he needed round the clock care. But he was able to live and die in his small apartment in assisted living. As an ethnography, Caring for Red provides a real sense of life in assisted living, the norms and values that drive human interaction, the hierarchy of staff, and the structures that define the experience within this institutional form of care that aims to provide a home-like environment.

GAYLE: Can you describe what Assisted Living is?

MINDY: Well, people think of it as kind of a hybrid health and home service, but in fact it’s really just more home than health oriented. It’s a place to live; there are regular meals; there often are activities; and staff provide services to residents – up to a point. Some assisted living facilities have medical staff; others don’t. We chose a place that had some nursing care, including medical people who delivered medications, and there was actually a doctor, a geriatrician, who came by once a week. But we had to pay for medical care because it was beyond the basic services offered. We ended up supplementing even more services in order to avoid having to send him to a nursing home. But that’s a longer story…

GAYLE: You were also a long-distance caregiver. How did you manage your father’s care from afar?

MINDY: I was lucky that I had a sister to do this with, so between the two of us we shared the caregiving work. We visited every weekend; we talked on the phone all the time; and we were on the phone constantly with caregivers, as well as his friends to help arrange his social life.

GAYLE: What do you hope for your book? How do you hope people will be affected by reading it?

MINDY: I guess if nothing else, I’d like it to contribute to a more open conversation about the trials and tribulations of caregiving work. While Caring for Red includes references to scholarly work on caregiving, I will be lucky if people feel more of a heart connection to the issues, particularly those people who are caring for an elder parent. We all have a range of feelings towards the people who cared for us when we were young. It’s important to recognize that there are a lot of people who love their parents; there are some people who hate their parents; and there are some people who have mixed feelings about their parents. Taking care of them in those final throes of life is jarring; AND it’s an opportunity to reconcile unresolved feelings; it’s an opportunity to treat elder parents with dignity and to make that last piece of life worth living. It’s also something that we’re all going to face at some point so I think that how we care for our parents is also a role model for how the younger people around us can – and hopefully will – care for us.

There’s no ultimate how-to book on caring for our parents. We all learn by what we see around us. So I’d like a dialogue to be stimulated about these issues. Because it’s very hard work – unpaid caregiving labor – and people don’t talk about this shit because it’s like, ‘oh it’s too depressing’, but hey, it’s life! We’re all going to die, you know, and somebody’s hopefully going to take care of us, so let’s think about how we want that to look within families and within society.

I also hope that academics will use this book in classes on aging, on death and dying, and on anything related to the life course. Moreover, Caring for Red is an ethnography, “set” in assisted living, so I hope it will be used in methods classes. And finally, for those who take interest in the history of facism and particularly, in the McCarthy era, the book presents quite a story, which I believe we must not lose.

GAYLE: Thank you, Mindy Fried. The deeply moving and insightful memoir – “Caring for Red”- is available for pre-order on Amazon.com.

by Mindy Fried | Sep 6, 2015 | aging, applied sociology, connections with people, engaged aging, gender, making choices, research, social science research, SWAN Study, women and health

I sit opposite Lila [1], the 25-year-old research assistant, in a small room at a satellite office of Mass General Hospital. She is warm and professional, and we have already discovered that she went to college at the same university where I went to graduate school. She took classes with some of my favorite professors, and we may have been in the same room at one point, when I came back to give a talk on campus. This is a nice ice-breaker. But now, in this room, Lila is in the driver’s seat. She has just finished asking me a load of questions about my health, lifestyle, and social networks. I will be there a total of four hours by the time I complete the entire process, which includes a bone density scan and a few other tests they’ve added this year.

I sit opposite Lila [1], the 25-year-old research assistant, in a small room at a satellite office of Mass General Hospital. She is warm and professional, and we have already discovered that she went to college at the same university where I went to graduate school. She took classes with some of my favorite professors, and we may have been in the same room at one point, when I came back to give a talk on campus. This is a nice ice-breaker. But now, in this room, Lila is in the driver’s seat. She has just finished asking me a load of questions about my health, lifestyle, and social networks. I will be there a total of four hours by the time I complete the entire process, which includes a bone density scan and a few other tests they’ve added this year.

In 1996, right after I completed my Ph.D. in Sociology, I was randomly selected as one of 3,302 women from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds to participate in this mid-life women’s health study called SWAN – or Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. The study is following women as we transition through menopause, to better understand the physical, biological, psychological and social changes we experience during this period. SWAN aims to help scientists, health care providers and women “learn how mid-life experiences affect health and quality of life during aging”. [2]

In 1996, right after I completed my Ph.D. in Sociology, I was randomly selected as one of 3,302 women from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds to participate in this mid-life women’s health study called SWAN – or Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. The study is following women as we transition through menopause, to better understand the physical, biological, psychological and social changes we experience during this period. SWAN aims to help scientists, health care providers and women “learn how mid-life experiences affect health and quality of life during aging”. [2]

SWAN participants or “subjects” were all between 42 and 52 years old “at baseline” – that, is, when the study began – and we represent seven cities around the country, including my own city of Boston.

When I got the call inviting me to join the SWAN study, I had just completed a lengthy project that involved a lot of interviewing. I welcomed the opportunity to answer someone else’s questions! It also felt great to be a part of important research that had the prospects of influencing medical science. But when I said “yes” to participating in SWAN nearly 20 years ago, I could not have predicted that I would be interviewed by at least 10 or more 20-something research assistants, most of them en route to medical school following this “real-life” experience.

Last year, there was a funding hiatus for the study. I was having a tough year myself and barely noticed that I hadn’t gotten my annual call to set up an appointment. Then a month ago, a letter arrived. SWAN was back in biz, and I’d be getting a call soon! I was thrilled that the study was re-funded in this era of budget cuts for basic science and social science research. I was also feeling grateful that my health was back on track. It struck me that SWAN gave me a regular opportunity to reflect on my life’s circumstances, and to think about how I’m handling growing older, even if it’s only because of a series of questions read to me by a young research assistant whom I’ve just met.

Lila was trained to draw blood, and as she jabs me with the needle, I think, wow, she’s pretty good. We continue to chat, as she measures my waist and hips, clocks how fast I can walk down the narrow hallway, and how long I can balance in a variety of different positions. I’m feeling pretty cocky, until we get to the cognitive test, which they instituted about four years ago. Even though I think my memory is pretty good, being quizzed by a millennial is unnerving. I tell Lila that this test makes me anxious, and she says “yeah, everyone hates it”. That’s only somewhat reassuring, but I appreciate her attempt to normalize my response. Once it’s over – after I spat back a series of numbers and letters in order, and re-told a story about three children in a burning house being saved by a brave fire fighter – I tell myself, “good enough”. That was something my father used to say in moments of stress.

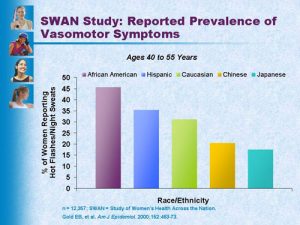

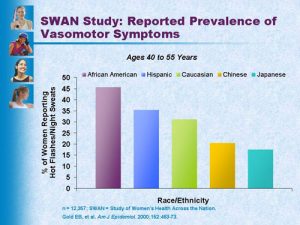

The SWAN Study has taken care to ensure that we are a diverse sample of participants.

- Prevalence of hot flashes by race/ethnicity

In Boston, researchers over-sampled African-American women, meaning that the study has intentionally included a larger percentage of African-Americans than are represented in the general population. Other cities have ensured that the sample includes large numbers of Chinese, Japanese, and Hispanic women. This oversampling strategy allows researchers to investigate the influence of race and ethnicity on health outcomes of women as we age.

SWAN-affiliated researchers, Drs. Robin Green and Nanette Santoro, found that most symptoms of menopausal women varied by ethnicity. They write,

“Vasomotor symptoms were more prevalent in African-American and Hispanic women and were also more common in women with greater BMI, challenging the widely held belief that obesity is protective against vasomotor symptoms”.

They also found that vaginal dryness was present in 30-40 percent of SWAN participants at baseline, and was most prevalent in Hispanic women. But even among Hispanic women, “symptoms varied by country of origin”. The researchers conclude that “acculturation appears to play a complex role in menopausal symptomatology” and that “ethnicity should be taken into account when interpreting menopausal symptom presentation in women”.

By including an ethnically diverse sample, the SWAN Study is able to compare the experiences of women from varied backgrounds, which has pointed to important differences that should be of great benefit to health care practitioners. Moreover, SWAN researchers provide participants with information about our health, and flag issues we should explore further. For example, I discovered that I had high cholesterol, something that runs in my family. I’m now being monitored by a specialist, who asked me to take a very lose dose of a Statin. And overall, I’m more conscientious about my diet. The upshot is that my cholesterol levels are under control.

Gathering the SWANS…

- Jocelyn Elders, former U.S. Surgeon General

In the past couple of decades, the SWAN team held a number of gatherings to bring Boston SWAN “subjects” together. It’s awesome to be in a room with hundreds of women with one thing in common: we are mid-life women who have gone through menopause! What fun to talk about all the crap we are experiencing without feeling judged or worrying that we might be boring someone.

The first gathering I attended offered workshops where “experts” could answer our questions about sleep (like hot flashes keeping us awake) or provide us with alternatives to Hormone Replacement Therapy. One year, SWAN researchers organized an event that featured the brilliant and outspoken Jocelyn Elders, former U.S. Surgeon General who was a lightning rod for speaking her mind, in support of legalizing marijuana, the distribution of contraceptives in schools, and even suggesting that masturbation might be a means of preventing young people from engaging in riskier forms of sexual activity. Sitting in a diverse crowd of mid-life women and cheering for Elders, whom I have admired for years, was positively thrilling.

Lila tells me a little about this year’s gathering, which I unfortunately missed. I learn that one of the Boston-based Principal Investigators, Dr. Joel Finkelstein, is a serious art aficionado and at the last SWAN Study gathering, he showed a series of paintings by an older woman. His message was that we can continue to grow and be creative as we age. When the interview is complete, Lila hands me my gift. In past years, it has been a cup or a small tote bag, marked with the graceful SWAN logo. But this year, it’s a small box, the top graced with a floral design from this artist.

In the abstract of his 2014 application to the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Finkelstein concluded by saying, “SWAN will fill important gaps in understanding the impact of the menopausal transition and mid-life aging on women’s health and functioning in the postmenopausal years. Accordingly, it will provide useful information to guide clinical decisions in mid-life and beyond in women who have diverse life experiences and socioeconomic and racial/ethnic characteristics”.

I’m grateful to be a part of this longitudinal study, to know that the aggregate data being collected reflects a diverse population of women, and that we are collectively contributing to scientific knowledge that can improve the lives of women as we age.

Finally, here’s a great clip from Menopause, the Musical!, just for fun: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ndFBFXV3jjs

[1] Fictitious name

[2] The SWAN Study is co-sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

by Mindy Fried | Apr 1, 2015 | adventure, applied sociology, careers, finding work, gender, making choices, program evaluation, race, social science research, sociology

When attempting to transform communities through social policy, it is imperative to not only understand what the social problem is, but also how and why it exists and persists. Trained sociologists have indispensable tools for this type of applied work. – Chantal Hailey

In my last blog post – Choosing Applied Sociology – I referred to a 2013 article in Inside Higher Ed in which Sociologist Roberta Spalter-Roth, from the American Sociological Association, comments that “In sociology, there is close to a perfect match between available jobs and new Ph.D.s”, if you take into account non-academic jobs (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/08/06/sociology-job-market-continues-recover-steadily). She notes that while these “applied” jobs often pay more than university teaching positions, graduates rarely know about them and professors may even discourage their students from entering these professions.

Unfortunately, the majority of Sociology grad students view the tenure-track job market as their only career choice, but there are many Sociologists who have chosen to work in applied settings. The skills gleaned through a Sociology degree are applicable – or dare I say, “marketable” – in a whole host of other venues, including government, corporations, and all sizes of nonprofits, local, state and national. We are researchers, lobbyists, program managers, teachers/trainers, and more.

![]()

I decided to organize a panel on this topic at the annual meeting of Sociologists for Women in Society, held in Washington, DC. And on February, 2015, three distinguished Applied Sociologists from the DC area presented about why they chose this route of practice, what they do and for which populations, and how they incorporate sociological principles into their work, framed by a race, class, gender lens. In this post, one of the speakers, Chantal Hailey, talks about her draw to applied work, which she began as a Sociology student at Howard University. After a number of years doing Applied Sociology, Chantal is now a first year doctoral student at New York University.

Mindy: What interested you in doing applied work?

Chantal: Throughout out my childhood, I lived, attended summer camps and had friends and family who lived in low-income urban neighborhoods. I was able to see how low-quality schools, subpar housing, limited opportunities and violence shaped young peoples’ lives and limited their potential. I had a passion to transform these communities into places where all people could thrive. But on the other hand, I was a nerd. I enjoyed research, history, math and statistics.

During my internship at a research branch of a community development corporation, I discovered that providing statistical trends on health, education, and housing to nonprofits could help them inform how they served low-income communities. I also discovered that the voices of women and people of color were sometimes absent from these discussions. I knew that in order to get a seat at the table, as a black woman, I needed to have the highest credential possible. So I began my academic journey at Howard University (as an) undergraduate in the Sociology department, knowing that my ultimate goal was to complete a doctoral degree in Sociology.

Mindy: Did you know you were learning about Applied Sociology at that point?

Chantal: While I was at Howard, I didn’t know of any distinction between applied and “pure” sociology. I just completed papers on topics that were important to me–public housing, poverty, and education. Urban Institute (UI) kept popping up in my literature reviews and I applied for internship there after my junior year.

Mindy: What did you do when you were at Urban Institute?

Chantal: At Urban Institute (UI), I transformed from an intern to a Research Assistant to a Research Associate. UI’s research is a combination of researcher-generated projects and responses to RFPs (Requests for Proposals). Two of my projects exemplify the type of applied sociology I was able to undertake at UI. The first is the “Long Term Outcomes for Chicago Public Housing Families” project (LTO). LTO is a 10-year longitudinal study of families whose Chicago public housing was demolished or revitalized through the Plan for Transformation. We employed mixed methodology – family surveys; in-depth interviews with heads of household, young adults and children; and administrative data review.

We found that after relocation from distressed public housing developments, families generally lived in better quality housing in safer neighborhoods, but many adults struggled with physical illnesses and youth suffered the consequences of chronic neighborhood violence.

Mindy: What was your role there? What did you do?

Chantal: As a team member in this project, I assisted in developing the survey, helped lead data analysis, generated the young adult interview guides and conducted in-depth interviews with the young people in the study. I also co-led and lead-authored research briefs on housing and neighborhood quality and youth. A research brief is a 15-20 page synopsis of research findings. Unlike most journal articles, there is not a long literature review.

This short article allows us to disseminate the findings to wide audiences. In addition to the standard research brief, we also produced blogs, HUD online journal articles, and radio reports; and briefed the Chicago Housing Authority, Senate committee members, and the press. LTO used sociological methods to understand policy, but intentionally shared this knowledge with wider policy makers and practitioners.

Mindy: You say that trained Sociologists have “indispensable tools” for applied sociology. Can you elaborate on this a bit?

Chantal: Sociology can address a plethora of subject areas that often intersect (i.e. inequality, education, crime and violence, health, etc.), and it unveils the mechanisms behind social problems. A Sociology education trains researchers to look for the hidden transcripts among social groups and interactions, not just the most apparent narrative. It allows for simultaneous macro, meso, and micro analysis to understand multiple contributing factors. And it emphasizes the impact social context has on policies’ implementation and outcomes.

This was especially apparent in the LTO study. We understood that in addition to families’ relocation from public housing, a series of key factors – including proliferating national rates of housing foreclosure, increasing Chicago neighborhood violence, and rising income inequality – also shaped families’ experiences in South Side Chicago neighborhoods.

A Sociology education provides an array of methodological tools that can be tailored to best address research questions (i.e. interviews, focus groups, ethnography, quantitative analysis). It pairs theories of race, class, family structure, etc. to better understand social issues. These analytic and research skills allow us to partner with government, non-profit, and academic agencies to both advance sociological theory and offer practical solutions to social problems.

Mindy: Thank you! And can you provide another example of applied work you’ve done, where you’ve been able to bring your analytic and research skills to the fore?

Chantal: In D.C., I participated in a Community Based Participatory Grant funded by NIH entitled Promoting Adolescent Sexual Safety (PASS). UI, University of California San Diego, D.C. Housing Authority, and D.C. public housing residents collaborated in the PASS project.

This research team – along with a mix of individuals from different racial, class, and professional backgrounds – aimed to develop a program to increase sexual health and decrease sexual violence.

Mindy: How did you use what you were learning as a Sociology student/practitioner?

Chantal: Again, we used sociological methods to conduct this project, including an adult and youth survey, in-depth interviews with community members, participant observations, and focus groups.

Mindy: You said this project was participatory. Can you talk about who was involved? How was it participatory?

Chantal: Through the grant, we developed a community advisory board, a group of 15 residents who participated in creating the PASS program. The interactions between the community advisory board, community practitioners, and the researchers challenged the researchers to not only study educational, class, geographic and racial inequalities, but also to assess how our interactions dismantled or exacerbated power inequities.

Mindy: Earlier, when we spoke, you talked about what it was like to be an African-American researcher who also had a personal understanding of the experience of people you were researching. Can you talk a little about that?

Chantal: As an African American woman on the project with family who lived in D.C., I was personally challenged to both create distance as a researcher and closeness as a fellow black D.C. resident. I often found myself “code-switching” during community meetings, as I communicated with both my co-workers and the community members. Feeling a responsibility to and, often, sympathizing with the desires of the researchers and the residents, I also had to sometimes explain and mediate diverging understandings during conflicts. This closeness and distance dichotomy was also pertinent during data analysis. While my experiences allowed me to recognize and interpret focus group participants’ terminologies and cultural cues, I had to ensure that my sympathies with the community did not cloud my ability to see inconvenient truths.

Mindy: And how did you get what you learned out there to your target audiences?

Chantal: This research project, like most UI projects, focused on dissemination to wider audiences in palatable formats–a community data walk, research briefs, blogs and journal articles.

Mindy: Finally…now you’re a doctoral student at NYU and studying Sociology. How do you see yourself moving forward as a Sociologist? How will you incorporate what you’ve learned into your future practice? (or is that something you’re still figuring out!)

Chantal: As I continue in graduate school at NYU, I aim to crystalize my research identity and trajectory. I have methodological and policy research experience through the Urban Institute, and I am gaining theoretical expertise while completing my doctoral degree. I hope to incorporate these elements into my research and become a conduit between academia, policy makers, and urban communities to make inner city neighborhoods a place where all children can thrive. A mentor once advised me that graduate school is a journey where you begin in one place and end in another. I am tooled with amazing applied experiences and I’m excited to see how my graduate school journey directs my path.

by Mindy Fried | May 2, 2014 | child care, early education and care, fathering, fathers, feminist, gender, Joe Ehrmann, making choices, mothers, New York Mets, parental leave policy, pro-feminist, Riverside High School, value of caregiving work

![]()

I was a high school cheerleader. Whew – I’ve gotten the confessional part of this post out of the way. In all honesty, I hated football, and didn’t know anything about the game. I had discovered ballet and modern dance at age seven, and very soon was taking lessons four times a week. Dance was my life. This was an era when girls were often discouraged or excluded from playing sports, before the passage of Title IX. When I reached Riverside High School (RHS) in Buffalo, New York, the only dance-like option available for athletic girls was cheerleading. So another dancer friend and I plunged into the world of rah-rah, feeling like outsiders even though we were viewed as football-loving cheerleaders. Perhaps more importantly, we were also considered “popular girls”, with status that was derived from our official role in supporting the football players, “our men”, who represented the epitome of masculinity.

![]()

Like most occupations that are female-dominated, our all-female cheerleading team was a vehicle through which we were able to bond. Our coach was the first lesbian I ever met, closeted of course in those days, who supported us in our prominent role, despite the fact that it was a gendered role. Our job was quite simple. We were to rev up the audience so that they could rev up the players. We cheerleaders – dressed in our short skirts and lettered sweaters – were happy to cheer and leap with chronically fixed smiles, as we performed to an appreciative crowd. Although unlike me, most of my “sisters” really meant it when they cheered for the players. Here was one of our popular chants, which I loved not because of the words, which glorified the heroes of the game, but because of the athletic moves that accompanied them:

“They always call him Mr. Touchdown

They always call him Mr. T.

He can run and and kick and throw

Give him the ball and just look at him go

Hip, hip, hooray for Mister Touch-down

He’s gonna beat ‘em today

So give a great big cheer (WOO! – cheers the crowd ) for the hero of the year,

Mister Touchdown, RHS (Riverside High School)”

![]()

The real hero of the RHS team was Joe Ehrmann, a star football player with a solid frame, wide, powerful neck, and muscles that popped out of his uniform. Unlike most other girls in school, I was not interested in football players, including Joe. I presumed – right or wrong – that if you were a football player, you probably had an inflated ego and you were short on smarts.

That said, it was clear that Joe was different than the other ball players. He was funny and clever, and a “mensch” – aka a really sweet guy. I remember his performance in an all-school “assembly” when Joe got up in front of the whole school and danced in a hula skirt. At the time, this was hysterical and unheard of – a popular football player cross-dressing for laughs. He wasn’t afraid to be outrageous, and perhaps understood that a hulk of a man displaying so-called femininity was discordant and therefore, funny.

No surprise that Joe and I didn’t see each other after high school, but we both attended Syracuse University. He went on to become a star player on SU’s football team, and I went on to become an anti-war activist and aspiring feminist. When Joe graduated from SU, he was immediately drafted to play defensive tackle in the NFL for the Baltimore Colts. Given my disconnect from the world of football – in my mind, a violent sport that typifies our “masculinist” culture – I knew nothing about Joe and his success over the next four decades. That is, until I began to teach courses on gender and workplace issues, and lo and behold, I discovered that Joe and I had a lot in common. Over the years, Joe had become a minister and popular motivational speaker who chose sports as his bully pulpit to preach all over the country about the damaging social construct of what it means “to be a man”.

In his blog, Joe writes about 10 lessons he’s learning about sports in America. Lesson # 7 says:

At the core of much of America’s social chaos – from boys with guns, to girls with babies, immorality in board rooms and the beat down women take– is the socialization of boys into men. Violence, a sense of superiority over women, and emotional disconnectedness are not inherent to masculinity – they are the results of societal messages that define and dictate American masculinity.

Speaking like a feminist sociologist, Joe says that “America is increasingly becoming a toxic environment for the development of boys into men”…which “disconnects a boy’s heart from his head (and) contributes to a culture of violence, emotional invulnerability, toughness and stoicism (that) perpetuates the challenge of helping boys become loving, contributing and productive citizens”.

![]()

I wouldn’t have found Joe, had I not become aware of a controversy around a couple of macho sportscasters who run a morning radio show on WFAN in New York City, called Boomer and Carton, followed by a social critique from my old classmate, Joe. The “Boomer and Carton” show began with Carton ranting about a New York Mets player, Daniel Murphy, who took two days of paternity leave, or as they called it a two-game paternity leave, to be with his wife as she was birthing their baby. He said that he could understand why a man would be with his wife while she’s HAVING the baby,

But to ME, and this is MY sensibility – Assuming the birth went well; assuming your wife is fine; assuming the baby is fine – (then he should take off) 24 hours! Baby’s good; you stay there; you have a good support system for the mom and the baby. (Then) you get your ass back to the team and you play baseball! That’s my take on it.

![]()

As Carton finishes these last words, he knocks his fist on the table, agitated, and then continues: “What do you need to do anyway? You’re not breastfeeding the kid!…I got four of these little rug rats! There’s nothing to do!”

Initially, Boomer counters by saying that Daniel Murphy has the legal right to be with the mom and his newborn, but when pressed by his co-host, Carton, about what HE would have done, Boomer backs off and says:

Quite frankly I would’ve said (to my wife), C-section before the season starts. I need to be at opening day. I’m sorry, this is what makes our money. This is how we’re going to live our life. This is going to give my child every opportunity to be a success in life. I’ll be able to afford any college I want to send my kid to because I’m a baseball player.

So here we have two sportscasters telling us that a) “real” men have no responsibility, nor should they have an interest in being an involved father; and b) “real” men should tell their wives that this is how it’s going to be: You wrap your birthing around my work schedule, and then when you’re done popping out the baby, I’m outa’ here because I’m making money to send this kid to college, and that’s more important.

This is where former NFL player Joe Ehrmann chimed in.

I think these comments are pretty shortsighted and reflect old school thinking about masculinity and fatherhood. Paternity leave is critical in helping dads create life-long bonding and sharing in the responsibilities of raising emotionally healthy children. To miss the life altering experience of ‘co-laboring’ in a delivery room due to nonessential work-related responsibilities is to create false values.

Take that, Boomer and Carton!

![]()

In the background throughout all this hub-bub was Daniel Murphy who, without any fanfare, commented that he did hear about the controversy around his leave-taking, but he didn’t care. “That’s the awesome part about being blessed, about being a parent, is you get that choice. My wife and I discussed it, and we felt the best thing for our family was for me to try to stay for an extra day – that being Wednesday, due to the fact that she can’t travel for two weeks”.

Instead of cow-towing to the traditional view that men – in particular, high-priced athletes – should put work over family, Murphy exhibited compassion for his wife and a desire to be an involved dad. “It’s going to be tough for her to get up to New York for a month. I can only speak from my experience – a father seeing his wife – she was completely finished. I mean, she was done. She had surgery and she was wiped. Having me there helped a lot, and vice versa, to take some of the load off. … It felt, for us, like the right decision to make.”

Okay, Murphy defended his right to take a measly two days off from work. This isn’t so different from thousands of men around the nation, as the range of men’s use of parental leave goes somewhere from a couple days to a couple of weeks. And that time is generally taken as vacation time, which disassociates it from the act of involved fathering. But still, the public face of this story elevates the importance of father involvement in child caring and co-parenting, with Murphy as the protagonist, and my old classmate, Joe, the advocate who understands and has a lot of important things to say about it.

![]()

Joe continues to give inspirational talks around the country, where he questions how men begin to understand themselves and connect more deeply to others. “It’s a long term process but it starts with the idea that you can’t keep hiding and protecting yourself. You’ve got to be able to let people in. Then you have a chance to be truly loved and to love.”

Check out Joe Ehrmann’s TedX Baltimore talk called “Be a Man”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jVI1Xutc_Ws

by Mindy Fried | Apr 20, 2014 | aging, connections with people, engaged aging, family, gender, making choices, retirement, social science research, women and work

re•tire [ri-tahyuh r]

1. to withdraw, or go away or apart, to a place of privacy, shelter, or seclusion: “He retired to his study”.

2. to fall back or retreat in an orderly fashion and according to plan, as from battle, an untenable position, danger, etc.

3. to withdraw or remove oneself: “After announcing the guests, the butler retired”.

4. to withdraw from office, business, or active life, usually because of age: to retire at the age of sixty.

5. retirement or withdrawal, as from worldly matters or the company of others.

One of my friends is passionate about Latin America and travels widely, monitoring elections and writing for an international journal. Her life-long “career” as an energy consultant is gradually shifting to her passionate “avocation”.

A family member who is a therapist decided to significantly pull back on her work hours, but then it didn’t “feel right”. Instead of leaving her practice, she decided to slow down the process, and continues to see clients. She is working fewer hours, spends more time with her children and grandchildren, and has increased her volunteer work.

Another friend had a decades-long successful career as a librarian. As her retirement approached, she was uncertain about what would come next, but stayed open to possibilities. She now works as a volunteer in a number of non-profit organizations, travels, reads, and has time to hang out with friends and former colleagues.

And me? I don’t plan to retire for a long time. First off, even though I’m technically approaching the typical “retirement age”, I like to work because I’d like to think that I’m contributing to making the world a slightly better place, at least in the small piece of the universe I inhabit. Maybe more basic is the fact that, like many people, I can’t afford to retire!

When it comes to major life changes, I like to be fully informed, so I decided to study “retirement narratives”. It’s an informal study that is personally driven by my desire to remain engaged in and satisfied with life when I stop working for pay someday (who knows which day). My study is a pre-emptive strike against loneliness and a concern that as I age, I will be on the periphery, no longer a contributor to the world, no longer a player in daily life…I know this can happen because I’ve seen it happen, and I bet you have too. My observations and intuition have been confirmed by reading a ton of books about aging, in preparation for an aging course I taught at Brandeis University, as well as following the substantial media coverage of issues of aging. My feeling was that my informal study would provide me with an opportunity to better understand this life changing event from a sociological perspective.

My role model for retirement was my father, who didn’t stop working in his job as an English professor until he was around 95 years old. I used to think that his formula – essentially, to never stop working – was how I wanted to live my life. I, too, imagined that I would basically work full-time until I dropped. But now I’m re-thinking my plans. And that’s where my research comes in. My study basically consists of informal “interviews” with friends who are reducing their paid work hours, as well as informal “chats” with acquaintances I run into in random places, like CVS, walking around Jamaica Pond, and on the street. For the people I know and with whom I have regular contact, I plan to follow them over a long period of time, meaning that I want to see what they do and how they adjust for as long as I know them, which could be until I or they die. With these friends, I hear the intimate details of their decision-making. Some of them had full-time jobs in organizations or institutions that provide incentives to retire, and some worried that they might lose their jobs past a certain age. Others work more autonomously as therapists or consultants.

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?

The research questions I employ with my “almost, kinda” friends have a one-two punch. We start by asking one another a few basic questions: “How are you?”, is the starter. Can’t get more basic than that! And then a probing question: “And what have you been up to?” Now this question also seems pretty basic but the reply reveals a lot through their words as well as their body language. If/when they say they’re retired – or just that they left their job of many years – my panoply of probes is unleashed and I ask, “Is it a good thing?” This is a general yes-no question, followed up by “How do you fill your days?” That’s the meat of what I’m looking for.

My informal study has no real parameters. My “sample” is fairly random; it’s not designed with any demographic in mind; I’ll talk to anyone. I’m not keeping track of how many people I’m interviewing, and I’m cool with going with the flow of the conversation, wherever it leads. I’m not discovering anything new, in a broader sense. There’s plenty of literature that argues for continued engagement in life, as one ages. Instead, my study is about getting at the particulars. What do people do as they’re considering retirement? Do they consciously prepare? Once they retire, what are they doing and how do they feel about it?

The issue of retirement has become even more salient because we are living longer. For example, in 2000, the life expectancy in the U.S. for women was 77.6, and for men it was 74.3. In 2010, those numbers had jumped to 79 and 76 respectively. It’s important to note that there is also a racial disparity, as reflected in 2010 figures, with white women projected to live until they are 81.3, and African-American women projected to live until they are 78. For men, the comparison between white and African-American men is 76.5 to 71.8, respectively.

Despite these gender and race disparities, an increase in longevity has resulted in a larger gap in time between official retirement and the point where people stop working for pay altogether. Dr. Mo Wang from the University of Maryland calls this period “post-retirement”, a time when people may choose self-employment, part-time work or temporary jobs. Dr. Jacquelyn B. James, from Boston College’s Sloan Center on Aging and Work (http://www.bc.edu/research/agingandwork/) calls this “transition” period “the “crown of life”, which implies that it is a special time, perhaps less fraught with the demands of one’s “regular” job which may have consumed years or decades of their lives. According to Wang’s research, “retirees who transition from full-time work into a temporary or part-time job experience fewer major diseases and are able to function better day-to-day than people who stop working altogether.”

At the same time, other research doesn’t focus on the impact of paid work; rather, it notes that as people age, those who stay engaged in life, both socially and intellectually, will fare much better than those who retreat, regardless if they are working for pay or doing something else like volunteering, doing unpaid caregiving work, or just about any activity that engages them.

In my effort to amass retirement narratives, I welcome you to tell me yours! It would be great to hear about your journey, whether you’re in the thinking stage or you have started instituting changes in your paid work schedule, or you have left a paid job and are in a next chapter of your life!

Also, just for fun, check out this video of a policy debate between Republican Paul Ryan who wants to increase the retirement age, claiming that the Social Security fund is depleted, and Democrat Debbie Wasserman Schultz, who strongly disagrees: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIrltAkTf38

by Mindy Fried | Nov 20, 2012 | aging, engaged aging, health, making choices, military family policies, women and self-esteem, women and work

I don’t know about you, but for a few days – well maybe a week – I was obsessed with the soap opera that unfolded with General Petraeus, Paula Broadwell, and the Kardashian-look-alike twins who throw champagne-infused parties for the military elite. Who knew that this world even existed?! It was temporarily intoxicating. That said, this is not a James Bond story, where seduction and hot sex are intertwined with power and our country’s national security. This is the everyday horror of people making terrible personal mistakes. And I’m not surprised that as readers try to make sense of the un-reality of “the facts”, a number of narratives about who to blame have been dusted off and brought to bear once again.

According to one narrative, the blame goes to the evil temptress, a Harvard-trained intellectual and top-of-the-line athlete (read: good in the sack) who brings down the CIA chief. Think Fatal Attraction, where the woman is in charge and the man is uncontrollably gripped by her charm and power, with no alternative but to succumb. In another narrative, the blame goes to the high-level spy who takes advantage of – no, seduces – the lower-level acolyte, and just cannot keep it zipped up, despite all his medals to the contrary. Think Bill Clinton, driven by self-destruction, someone who acts first and thinks later. Hardly the image one wants to conjure up for the head of the CIA. Less prominent, but implicit among these narratives, is the role of the spy guy’s wife, who is subtly blamed for not satisfying her man. This narrative blames her because she’s middle-aged (read, unattractive), with the assumption is that she no longer has the goods. Narrative three then morphs into narrative two, which combines with narrative one, in which said high-level spy has no alternative but to explore younger, more supple, women, and one of them just happens to be out to get him. A perfect storm…

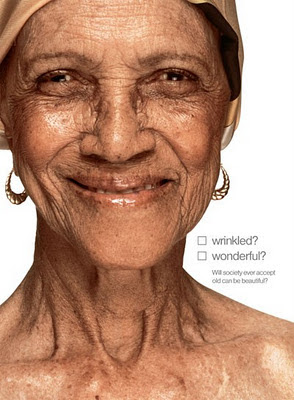

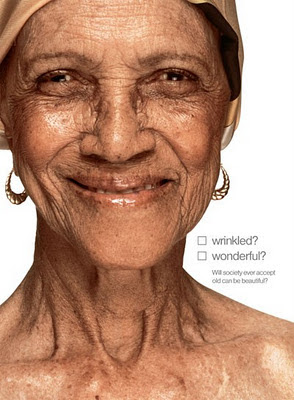

While there might be some bitter truth in all of these narratives, I’d like to focus on that last one, which capitalizes on the notion that older guys get more sexy, in contrast to older women, who get more dowdy, wrinkly and saggy as we age. This narrative has it that as women get older, we lose our appeal; we no longer shine; we fade; we become less attractive. And barring heavy use of botox and liposuction, that so-called “fact” is justification for our men to rove.

Now back to the Petraeus “affair”. Thankfully, the media is not exploiting Holly Petreaus’ story, only to say that she is furious. (Wouldn’t you be if you happened to be married to this adulterous four-star General? Okay, maybe you find it hard to imagine that you’d marry this dude…) But according to military spouse and marriage consultant, Jacey Eckhart, this telenovella (melodramatic soap opera in Spanish) has fired up fears among other military spouses, who are worried that their marriages will follow suit. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/16/opinion/the-petraeus-effect-on-military-marriage.html?ref=opinion

While Eckhart, a competent, articulate military spouse, knows rationally that she has nothing to worry about in her own relationship, she says the scandal has “reduced me to a wet towel and tears”. Why? Because she says that men, as they age, become more like Cary Grant, and women become more like the older “Tony Curtis”, meaning old (and kinda gay). Granted (no pun intended), military families endure enormous strains because they move frequently, and often it is the spouse who helps their family settle in a new area while the military “member” is off fighting a war (or hopefully keeping peace somewhere in the world!).

Moreover, repeat deployments place even more strain on the family, both when the military member is gone, as well as when s/he comes back, after having been traumatized by the experience of war. But separation of military spouses and their families – and ensuing loneliness – is the issue, not whether a woman can stay hot enough to hold onto her man.

Eckert laments that “history isn’t enough to keep a long military marriage together”. At the same time, she notes that military marriages end at the same rate as so-called civilian marriages. So what’s the big deal?! The problem isn’t that men will be men, and women should quiver in their boots for fear they will be cast off for a better model. The problem is that we gals sometimes internalize the societal notions that our shelf lives have expired once we hit 40 or 50 or 60. Instead of buying into – or internalizing – these lethal notions, we need to embrace the woman we are becoming, our all-inclusive selves, including our wisdom about people and life, and even the tell-tale wrinkles and sags and possibly even the dowdiness. Let’s not compare ourselves to younger women and feel self-critical. The reality is that we are all the ages we have been, and so much more. Of course, it’s important that we take care of ourselves – that we eat well, and remain active intellectually and physically; those lifestyle choices are critical if we want to live a long life. But ultimately, our worth should not be measured by our youthfulness. Even the General is now saying it was a big mistake…

GAYLE: Mindy Fried, your new book Caring for Red tells a story of you and your sister taking care of your 97-old father in the last year of his life in an assisted living facility. Before we talk about your experience caring for your dad, Manny, tell me a little about him. Who was this colorful character? After all, he earned the nickname “Red.” Sounds fiery to me!

GAYLE: Mindy Fried, your new book Caring for Red tells a story of you and your sister taking care of your 97-old father in the last year of his life in an assisted living facility. Before we talk about your experience caring for your dad, Manny, tell me a little about him. Who was this colorful character? After all, he earned the nickname “Red.” Sounds fiery to me!

I sit opposite Lila

I sit opposite Lila