by Mindy Fried | Apr 20, 2014 | aging, connections with people, engaged aging, family, gender, making choices, retirement, social science research, women and work

re•tire [ri-tahyuh r]

1. to withdraw, or go away or apart, to a place of privacy, shelter, or seclusion: “He retired to his study”.

2. to fall back or retreat in an orderly fashion and according to plan, as from battle, an untenable position, danger, etc.

3. to withdraw or remove oneself: “After announcing the guests, the butler retired”.

4. to withdraw from office, business, or active life, usually because of age: to retire at the age of sixty.

5. retirement or withdrawal, as from worldly matters or the company of others.

One of my friends is passionate about Latin America and travels widely, monitoring elections and writing for an international journal. Her life-long “career” as an energy consultant is gradually shifting to her passionate “avocation”.

A family member who is a therapist decided to significantly pull back on her work hours, but then it didn’t “feel right”. Instead of leaving her practice, she decided to slow down the process, and continues to see clients. She is working fewer hours, spends more time with her children and grandchildren, and has increased her volunteer work.

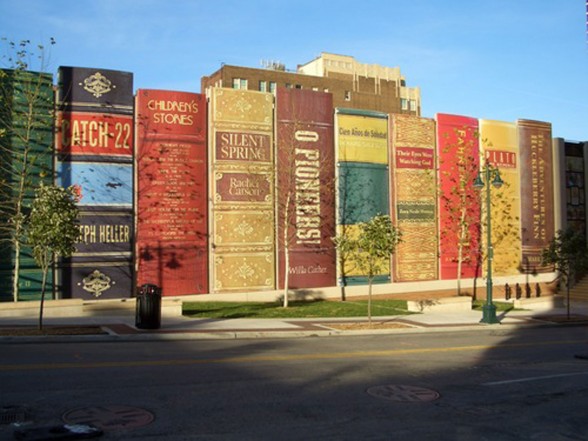

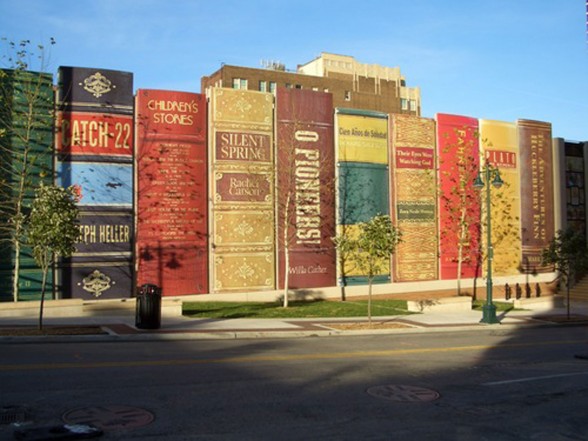

Another friend had a decades-long successful career as a librarian. As her retirement approached, she was uncertain about what would come next, but stayed open to possibilities. She now works as a volunteer in a number of non-profit organizations, travels, reads, and has time to hang out with friends and former colleagues.

And me? I don’t plan to retire for a long time. First off, even though I’m technically approaching the typical “retirement age”, I like to work because I’d like to think that I’m contributing to making the world a slightly better place, at least in the small piece of the universe I inhabit. Maybe more basic is the fact that, like many people, I can’t afford to retire!

When it comes to major life changes, I like to be fully informed, so I decided to study “retirement narratives”. It’s an informal study that is personally driven by my desire to remain engaged in and satisfied with life when I stop working for pay someday (who knows which day). My study is a pre-emptive strike against loneliness and a concern that as I age, I will be on the periphery, no longer a contributor to the world, no longer a player in daily life…I know this can happen because I’ve seen it happen, and I bet you have too. My observations and intuition have been confirmed by reading a ton of books about aging, in preparation for an aging course I taught at Brandeis University, as well as following the substantial media coverage of issues of aging. My feeling was that my informal study would provide me with an opportunity to better understand this life changing event from a sociological perspective.

My role model for retirement was my father, who didn’t stop working in his job as an English professor until he was around 95 years old. I used to think that his formula – essentially, to never stop working – was how I wanted to live my life. I, too, imagined that I would basically work full-time until I dropped. But now I’m re-thinking my plans. And that’s where my research comes in. My study basically consists of informal “interviews” with friends who are reducing their paid work hours, as well as informal “chats” with acquaintances I run into in random places, like CVS, walking around Jamaica Pond, and on the street. For the people I know and with whom I have regular contact, I plan to follow them over a long period of time, meaning that I want to see what they do and how they adjust for as long as I know them, which could be until I or they die. With these friends, I hear the intimate details of their decision-making. Some of them had full-time jobs in organizations or institutions that provide incentives to retire, and some worried that they might lose their jobs past a certain age. Others work more autonomously as therapists or consultants.

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?

The research questions I employ with my “almost, kinda” friends have a one-two punch. We start by asking one another a few basic questions: “How are you?”, is the starter. Can’t get more basic than that! And then a probing question: “And what have you been up to?” Now this question also seems pretty basic but the reply reveals a lot through their words as well as their body language. If/when they say they’re retired – or just that they left their job of many years – my panoply of probes is unleashed and I ask, “Is it a good thing?” This is a general yes-no question, followed up by “How do you fill your days?” That’s the meat of what I’m looking for.

My informal study has no real parameters. My “sample” is fairly random; it’s not designed with any demographic in mind; I’ll talk to anyone. I’m not keeping track of how many people I’m interviewing, and I’m cool with going with the flow of the conversation, wherever it leads. I’m not discovering anything new, in a broader sense. There’s plenty of literature that argues for continued engagement in life, as one ages. Instead, my study is about getting at the particulars. What do people do as they’re considering retirement? Do they consciously prepare? Once they retire, what are they doing and how do they feel about it?

The issue of retirement has become even more salient because we are living longer. For example, in 2000, the life expectancy in the U.S. for women was 77.6, and for men it was 74.3. In 2010, those numbers had jumped to 79 and 76 respectively. It’s important to note that there is also a racial disparity, as reflected in 2010 figures, with white women projected to live until they are 81.3, and African-American women projected to live until they are 78. For men, the comparison between white and African-American men is 76.5 to 71.8, respectively.

Despite these gender and race disparities, an increase in longevity has resulted in a larger gap in time between official retirement and the point where people stop working for pay altogether. Dr. Mo Wang from the University of Maryland calls this period “post-retirement”, a time when people may choose self-employment, part-time work or temporary jobs. Dr. Jacquelyn B. James, from Boston College’s Sloan Center on Aging and Work (http://www.bc.edu/research/agingandwork/) calls this “transition” period “the “crown of life”, which implies that it is a special time, perhaps less fraught with the demands of one’s “regular” job which may have consumed years or decades of their lives. According to Wang’s research, “retirees who transition from full-time work into a temporary or part-time job experience fewer major diseases and are able to function better day-to-day than people who stop working altogether.”

At the same time, other research doesn’t focus on the impact of paid work; rather, it notes that as people age, those who stay engaged in life, both socially and intellectually, will fare much better than those who retreat, regardless if they are working for pay or doing something else like volunteering, doing unpaid caregiving work, or just about any activity that engages them.

In my effort to amass retirement narratives, I welcome you to tell me yours! It would be great to hear about your journey, whether you’re in the thinking stage or you have started instituting changes in your paid work schedule, or you have left a paid job and are in a next chapter of your life!

Also, just for fun, check out this video of a policy debate between Republican Paul Ryan who wants to increase the retirement age, claiming that the Social Security fund is depleted, and Democrat Debbie Wasserman Schultz, who strongly disagrees: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIrltAkTf38

by Mindy Fried | Nov 5, 2013 | Uncategorized

I was listening to a new EP by a talented musician named Nathalie Raedler and discovered a song called One Night Stand https://soundcloud.com/nraedler/one-night-stand, that poignantly describes an experience that inspired her song. It got me thinking about how much progress women have and have not made over the past few decades around sexuality and relationships, particularly young women, including and maybe especially college-age women.

As a “veteran” of the 1970’s women’s movement – or what is now being called the Second Wave – I was part of a women’s group that met weekly to read and discuss historical and contemporary feminist articles, and to support one another in applying feminist principles in our personal and professional relationships. We “took charge” of certain activities that were typically done by men at the time, like changing tires and oil, and doing basic home repair.

![]()

I remember how thrilled I was to change a doorknob and shingle a house on Cape Cod! We analyzed popular culture to understand how it was reflecting and promoting gender imbalance, and over endless cups of coffee, we bonded as friends and as change-makers, taking charge of our relationships, our bodies and our lives. A small group of us published a newspaper called “New Salt City Press”, which reviewed films and major national and international news, including a how to column on topics like car repair and how to winterize your home. Our underlying message was an echo of women’s cries during World War II – We Can Do It!

While we were not a part of the “free love movement” – that was another “faction” of cultural change at the time – we also believed that women had the agency to determine how we wanted to engage in sexual and other types of relationships.

A few decades later, I joined the Women’s Caucus at Occupy Boston, a group of women who came together because a couple of women who lived in the encampment had been sexually assaulted, and moreover, they felt men were dominating the conversation at the encampment. I was disturbed to hear about these problems, but curious about and ultimately impressed with these women, many of whom had literally been schooled in universities around the country to understand and confront sexism. I discovered that the spirit of women-oriented culture lived on among these young women, who were both lesbian and heterosexual, in a “third wave” of the feminist movement. Men were still dominating the mainstream culture at Occupy, a microcosm of the broader society.

![]()

But without much backlash – a sign of changing times – these women at the encampment made great strides in inserting their voices into the conversation, organizing a successful “women’s” march, a speak-out on violence at the encampment, and sponsoring women speakers on reproductive rights, rigged ballots and gender and unemployment. Certainly what was different from 30 years before was that this “third wave” was bringing its collective voice to this particular table successfully. Despite enormous strides women have made in both the work and domestic spheres, it still seemed that young women – college age and in their early 20s – were experiencing gender imbalances in relationships with men.

Musician Nathalie Raedler captures the experience of this imbalance in One Night Stand, which she wrote after spending a night out with a group of “guy friends”. In this song, she describes how her “guy friends” had spent most of the night assessing women as possible pickup material, based on various body parts.

Their banter didn’t result in anyone taking anybody home that night, as far as she knew, but it did reinforce the bond between and among them, as they entertained one another with the assumption that the women were there for the taking. Did they think that their banter would also impress her? Or did she become invisible as they focused their energy on objectifying the women around them?

This male bonding over sexual exploits is explored in depth by sociologist Danielle Currier, in a recent Gender and Society article, based on her qualitative study on hookups among college-aged women and men. Based on interviews with 78 full-time, heterosexual students at a coed, public university in the South, Currier found that hooking up is common among college students, but there remains a sexual double standard. All of her study participants report that hookups are “ever present and normative in college and a central component of social life”, women participants disregarded their own sexual desires, performing oral sex on men without reciprocation and “ignoring their right to sexual pleasure in hookups”. As one of her participants said, “sex is defined as over when the guy climaxes”. Pleasure is equated with orgasm for men, rather than the full array of physical and emotional experiences associated with sexuality. Currier concludes that a central aspect of this configuration is “gender asymmetry”, with the assumption that men will achieve sexual satisfaction in hookups, and women’s role is to help them achieve this goal. Another critical aspect of her analysis is that women want to avoid being labeled a “slut”, worried about whether they will be viewed as having “too many” hookups. Women were “strategically ambiguous” about the nature of their hookups, not talking about them, and being vague about the details, to avoid this label which was applied only to women, not men, reflecting the “underlying double standard” used in labeling the nature of and amount of their sexual activity.

![]()

The aforementioned finding in Currier’s research, which Nathalie Raedler gives voice to in One Night Stand, is the “importance of bonding with or impressing other men, much more than bonding with or oppressing women”. Currier concludes that the gender imbalance in hookups is evidence of how “emphasized femininity is often a reaction to or an offshoot of hegemonic masculinity”. Moreover, “doing femininity still often means reacting to men and cultural definitions of masculinity”. In her song, Raedler describes the men as “hunting down random chicks”, asserting that the men have “nothing in your head. That’s why you have to think with your dick”. To the women, she asks “are you looking for someone? You’re selling yourself cheap.” Her song challenges men and women to undo this gendered configuration. Check out her song and new album: http://www.nathalieraedler.com/. Raedler has a beautiful and strong voice and a lot to say, and in a marriage of art and scholarship, Currier’s research captures the essence of Nathalie’s song with a strong scholarly piece of research.

by Mindy Fried | May 5, 2013 | aging, anxiety, community, depression, homophobia, insomnia, prejudice, racism, sexism, stress, women and health, work

The men in my family were easy sleepers. It wasn’t uncommon to see my father and his six brothers lie down on the floor after a big meal and just nod out. Of course, that left my aunts to clean up, after they had also cooked the meal, and I bet they could have used a nap too. At the time, I figured that taking a post-meal snooze was the “way things were” for the men in the family. But gradually, as I developed a feminist consciousness, I resented these lazy guys. As my age gradually crept up to where theirs were back then, I have begun to appreciate their supreme capacity to sleep just about anywhere, anytime. My father was also one of those people who could nod out for five minutes – taking a so-called “power nap” – only to emerge refreshed and able to fully re-enter the conversation when he awoke.

Later, when he was in his 90s, he began to experience serious insomnia, lying awake for hours and hours throughout the night, going crazy with boredom and frustration. While I sympathized with his dilemma at the time, it wasn’t until I experienced my own sustained insomnia – after a back injury – that I understood how horrible it is to not be able to sleep night after night. I discovered that sleep deprivation steals one’s energy, one’s optimism, and sometimes even one’s sanity. With increasing lack of sleep, the exhaustion compounds and the world becomes slightly, if not majorly, off-kilter.

![]()

Insomnia is a lot of things, which includes having a hard time getting to sleep, as well as waking up early and having a difficult time getting back to sleep. Not surprisingly, it isn’t a contemporary phenomenon. No, we in the so-called modern world didn’t invent it. Insomnia goes way, way back. The term “insomnia” first appeared in 1623, and means “want of sleep”. One of the biggest causes of insomnia, stress, is something that people have been struggling with for eons. It’s just the nature of stress that looks slightly different these days, compared to a few centuries ago. But if you think about it, there are a lot of similarities.

We’re stressed because we work hard or we don’t have enough work. We’re stressed because we live in a violent world that is unpredictable. We’re stressed if we experience social isolation or prejudice. We’re stressed when we don’t have enough to eat, and don’t know where the next meal is coming from. We’re stressed because our jobs are too demanding or not challenging enough. We’re stressed because we worry about paying our bills. We’re stressed because we don’t feel loved enough, or because we have tension with our partners or our friends. One might call these universal problems, and these stressers will vary based on your economic situation as well as your race, gender and sexual identity. And maybe a few centuries ago, we might have also worried about predators or major diseases that wiped out entire swaths of people. All of these stressors can lead to loss of sleep.

![]()

A lot of famous people are recorded as having suffered from insomnia. Sir Isaac Newton suffered from depression and had difficulty sleeping. Winston Churchill had two beds because if he couldn’t sleep in one, he would try the other. Thomas Edison, like my father, was a cat-napper, because he couldn’t sleep at night. Some insomniacs turned to drugs. Marcel Proust and Marilyn Monroe took barbiturates to help them sleep. English writer, Evelyn Waugh, took bromides to induce sleep. As we know, Michael Jackson died because of a lethal cocktail of medications to help him sleep, including propofal, used for sedation before surgeries, lorazepam, used for anxiety, and a host of other meds, including midazolam, diazepam, lidocaine and ephedrine. He was obviously so desperate to sleep that he was willing to try them all.

![]()

Author and columnist Arianna Huffington calls insomnia a “feminist issue”, and has written columns in Huffington Post lamenting her lack of sleep from jet lag. Another Huff Post columnist, Dora Levy Mossanen, calls insomnia a “smart, devious virus that mutates and changes form every season like the flu virus. Except that this tricky bugger is tuned to our circadian rhythm and is able to change and disguise itself at whim to confuse the heck out of us”. Mossanen does all the “right things”: She doesn’t drink caffeine, goes to bed at a decent hour, drinks hot milk before bedtime, takes warm baths, reads non-stimulating books, listens to guided meditation on her i-pod, and imagines serene seashores. And yet she says, “I toss and turn at the beginning of the night, counting backwards and forwards so many times that if my mind was prone to mathematics, I’d have solved all the mathematical problems of the world by now”.

For the most part, my insomnia has cleared, but every so often it rears its ugly head. While in the midst of a minor insomniac “relapse”, I asked my friends and colleagues for their insomnia narratives. I wanted to know how long their insomnia lasted, why they thought they were struggling with sleep; what they did when they were awake; how it affected them the next day. I learned that the main causes of insomnia are:

* Anxiety, the everyday kind like preparing to teach a class, and larger anxieties, like worrying about keeping a job;

* Depression, which impedes relaxation necessary to fall and stay asleep;

* Medications, because some meds like decongestants and pain meds keep us awake. Antihistamines might initially make us groggy, but they can cause excess urination which gets us up a lot during the night;

* Alcohol, which may make you more relaxed, but prevents deeper stages of sleep and can cause you to wake up in the middle of the night;

* Chronic pain, which is distracting and worrisome and can lead to anxiety, which prevents sleep;

* Medical conditions, like arthritis, cancer, heart disease and Parkinson’s disease, which are linked with insomnia;

* Poor sleep habits, like weird sleep schedules, or an uncomfortable sleep environment;

* “Learned insomnia” – which is worrying too much about not being able to sleep, which makes it hard to get to sleep; and

* Eating too much before sleeping or eating the wrong snack, which can give you heartburn and make it uncomfortable to fall sleep.

In response to my call for insomnia stories, only women replied. I know that isn’t because men don’t experience insomnia; but perhaps men don’t want to reveal their sleeping problems publicly, even though I promised confidentiality. (It’s not too late, for my male readers!)

One woman said, “You do realize you’ve opened the floodgates, yes? Amazing topic. Of course, I’m too sleep-deprived and deep into end-of-semester madness to respond right now! Maybe during my next bout of insomnia (perhaps tonite). ;-)”

Here are a few responses from other insomniacs:

One woman says, “Funny you should ask, as I am suffering from insomnia just now, maybe a week long bout this time, but by far not the longest ever. I wake up about 4am and cannot fall back asleep if my life depended on it. Not sure why I have such a hard time staying asleep, maybe it’s hormonal (menopause) or maybe it’s all the craziness at the office (new department chair, no office support as the old secretary retired, research lagging, …). Often I am not the only one awake, as my spouse is also a stressed-out insomniac. I typically try to fall back asleep, but if it doesn’t happen, I get up and read in the living room until I feel exhausted from being up at 4 am. What sometimes works is counting backwards from 100 in another language. Needless to say, the next day I feel a bit out of it, but nothing like the “zombieness” I did when my child used to wake me up. I am not desperate yet, but may try to find my melatonin from the previous bout to get me back on track. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t”.

Another woman says, “My insomnia stories are boring. I get up and clean the house, read, catch up and/or get ahead on my work. That makes me feel like I am not wasting my time trying to fall asleep. Usually that day I am racing, energetic and feel good about all I have accomplished. By that night I am crashing and I pay the next day in bodily aches/pain. Not very exciting…”

Another says, “I have had quite a few episodes of insomnia. There were times when I would go days or even a week without adequate sleep. I would either fall asleep and then wake up in the middle of the night and not be able to go back to bed, or I would just simply stare at the ceiling until I finally fell asleep, only to wake up about every half an hour for the rest of the night. Either way, insomnia sucks! I eventually couldn’t take it any longer and sought medical help. Come to find out, I have general anxiety disorder and that was greatly affecting my sleep. Even now – I am on medication- I still have bouts of insomnia when I am highly stressed. My mind is constantly going, so when something important is coming up I find myself having trouble sleeping. In the middle of the night I have tried a number of things: read a book, go to the gym (thank you, 24 hour fitness), eat, watch TV, and try and go back to sleep. As a student, during the day I am pretty much reading, writing, researching, or preparing for a class I TA for.

“After a night of insomnia, I usually feel terrible the next day. Even if I am tired, I don’t try and nap because if I do, the likelihood of getting a good night’s sleep decreases. If I go a few days or even a week without sleep, my brain has pretty much checked out. I go through the motions but I don’t feel like I am really all there. Hopefully that makes sense. Insights? I would say that everyone is different and should try different things to help them sleep. I hate taking medicine, even when I am sick, so seeing a doctor was the last thing on my list. I tried doing yoga, eating better, not watching TV or reading at night…but nothing helped me. Being put on medication was a great relief because I sleep really well, for the most part”.

And finally, one of my neighbors says, “Sometimes I look out the window to see who else might be up in the neighborhood. I am tempted to text them or call and get together, maybe we should start an insomniac club”.

That sounds tempting… I suppose that one strategy I’m employing is writing this post. Maybe “outing myself” as an insomniac will help diffuse the potency of this insidious problem. If I were to characterize my current “brand” of insomnia, it’s “learned insomnia”, meaning that I begin to fall asleep and then just as I’m fading into a hazy fog, my brain says “you’re falling asleep”, at which point I’m awake! Luckily, the problem has lessened since I first put out the call for insomnia stories. May it fade away!

Tell me your insomnia story! What has helped you overcome your sleeplessness?

by Mindy Fried | Apr 8, 2013 | child care, health care, inequality, Marissa Bayer, parental leave policy, Sheryl Sandberg, social policy, value of caregiving work, women and work, women managers, work and family balance, work culture

What happens when some women break the glass ceiling? A few of them become authors of best-selling novels in which they deconstruct their workplace experiences and offer advice to others. This is a good thing, in the tradition of sisters helping one another out. But which sisters and what kind of advice do they offer? Perhaps the most popular and controversial of the genre right now is Lean In, authored by Facebook Executive, Sheryl Sandberg, who authored an endearingly honest and forthright book about what women need to do to overcome obstacles and move up the career ladder. What I love about Sandberg’s writing is that she has broken the code of silence about what it feels like to be a woman in corporate America. She does it with personal stories about her own insecurities and vulnerabilities as a woman manager, as well as with facts about the gendered workplace, acknowledging the uneven playing field in which a preponderance of men dominate top positions in business and government.

I’m sure that her message resonates with thousands of professional working women across America. But Sandberg’s narrative unfortunately does not speak to women in non-professional jobs, where being assertive in the workplace doesn’t get you more; in fact, it just might get you fired. In fact, most women workers aren’t aiming for the top; they’re simply trying to make ends meet.

I’m sure that her message resonates with thousands of professional working women across America. But Sandberg’s narrative unfortunately does not speak to women in non-professional jobs, where being assertive in the workplace doesn’t get you more; in fact, it just might get you fired. In fact, most women workers aren’t aiming for the top; they’re simply trying to make ends meet.

One could argue that having women on top will make it better for all women, but that’s not necessarily the case. All the stereotypes that persist about women in the broader society – their inability to be assertive or think rationally in a crisis – become the yardsticks of assessment of women’s behavior when they are in management positions. Simply because they are women, they are judged more critically and closely. Not only is this personally uncomfortable for them; it may also affect their status in a company or government organization. Women on top must develop survival strategies to deal with pervasive sexism they experience on a daily basis.

They are subject to a dominant workplace culture in America that overvalues long hours as a measure of commitment and loyalty. This is the backdrop against which women in management – or high level positions – operate. When women upper-level managers make policies about their subordinates’ work policies, they are operating in a “gender-loaded zone”, in which their decisions may be scrutinized by their male colleagues.

We don’t need to look far to find a top female manager, Yahoo’s CEO Marissa Bayer, who offers a great example of this phenomenon with her recent announcement that she is eliminating telecommuting for her employees. http://www.forbes.com/sites/jennagoudreau/2013/02/25/back-to-the-stone-age-new-yahoo-ceo-marissa-mayer-bans-working-from-home/ This decree is counter to reams of data that support telecommuting as a cost-saving measure that may even increase worker productivity http://mindysmuses.blogspot.com/2010/12/telecommuting-its-about-time-and-place.html. In fact, the data is so strong that the U.S. now has a national telecommuting policy that applies to all federal workers, enacted as a result of the Telework Enhancement Act of 2010.

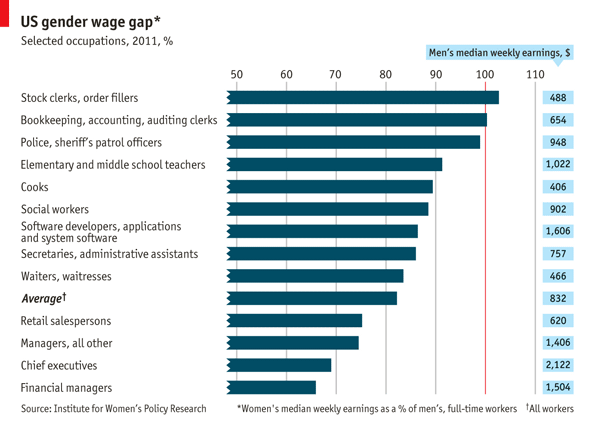

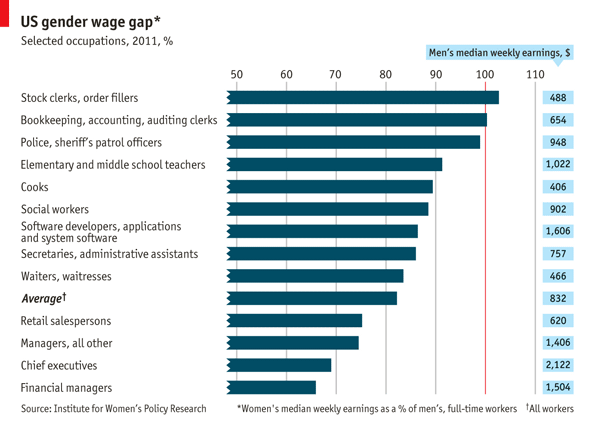

The reality is that professions that are dominated by men pay more, and those that are dominated by women pay less (e.g., programming vs. coding, doctoring vs. nursing, tenure track teaching job vs teaching kindergarten). One strategy is to encourage more women to pursue higher paid professions, and that’s fine. But this doesn’t address the devaluing of jobs that are more “gender-coded” like teaching, nursing, and anything related to caregiving work.

While I fully support the notion of women asserting themselves in the workplace (when it isn’t too risky!), many women – and men – would benefit from a range of public policies that protect their jobs and support their capacity to balance their work lives with their personal – including family – demands. In my own research on parental leave use in a large financial services corporation, I found that upper-level women didn’t use the policy AT ALL, largely because they either didn’t have kids (was this a business decision?) or because they waited until their children were older before going after upper management jobs. Women in middle-management used less leave time than they were legally allowed to take, and women in lower-level jobs took the least amount of leave time. What about men? They tended not to use the parental leave policy at all; rather, they took two weeks of vacation time after the birth or adoption of a new baby. What I found was two-fold: Given that we only have an unpaid leave policy in the U.S. (counter to most other industrial countries that provide paid leaves), family economics often called for the lower-paid worker to take time off to care for a newly arrived baby, and that was usually a woman. Moreover, the culture of the workplace rewards long hours, so that parental leave is considered time “taken” away from the job (e.g., profits) over time taken to parent, an unpaid job that is devalued by business norms. Hence the title of my book: Taking Time: Parental Leave Policy and Corporate Culture. http://www.amazon.com/Taking-Time-Women-Political-Economy/dp/1566396476

A more complete picture – one that addresses the needs of all workers – must include a set of universal policies, including pay equity to break down gendered wage differentials, paid parental leave to ensure that women AND men use leave time, flexible work policies that allow people to balance their work and personal demands, and universal child care to ensure that all young children have access to quality, affordable early care and education. In addition to offering advice about being more assertive in the workplace, we need these policies if we are to make any inroads towards changing the playing field for women and men. Moreover, for those in non-management positions, there must be formal policies as well as informal organizational support to ensure that being assertive in the workplace won’t cost them their jobs.

How can we enhance the recent messaging around women in the workplace to ensure that it addresses not only the micro level – how we as women and men operate in the context of our workplaces – but also the macro level, how workplace policies – including family policies – are needed to establish protections in the workplace?

by Mindy Fried | Mar 12, 2013 | arts, arts education, AWP conference, creative writing, loss, sociological imagination, women and work, women artists

Writing is a solo act, but for those in attendance at the conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, or AWP (https://www.awpwriter.org/) this past weekend, you’d think it was one big party, with over 12,000 people moving through the sterile hallways of Boston’s massive Hynes Convention Center to attend hundreds of sessions. I had been forewarned that this event was downright overwhelming. So before I stepped foot into the Hynes, I carefully studied the program, selected sessions that fit my criteria, and found out exactly where they were physically located. Getting lost in the Convention Center was not on my agenda! As it turned out, this surgical approach served me well.

In one day, I managed to attend five sessions, chat with five random strangers, purchase an energy bar for nearly $5, and wander around the book fair where I was invited by at least five non-residency writing programs to look at their literature. I spoke with five or so small presses about their books, and was also accosted by a woman selling a weeklong “writing trip” to Paris, which was, in sum, a total rip-off. Of my small sample of informal interviewees, a few were undergraduate creative writing majors who were totally blown away by the panoply of rich resources in one place; one was an art history professor and another was a writing professor.

But I wasn’t there to make friends, although later I joined the Women’s Caucus of the organization (yes, there is gender bias everywhere!). I was there because I’m writing a memoir about the experience of caring for my dad in his final year of life, in which I am inter-weaving my family’s experience of political persecution, the FBI and more. I wanted to hear published authors talk about their experience writing memoirs, and to garner some tips about the process of publishing this type of book.

Here are a few gems that I got from the conference:

In a panel called “The Art of Losing”, authors talked about how profound personal loss fuels their writing. One of my favorite speakers on this panel was Jennine Capó Cruce, author of How to Leave Hialeah (http://www.jcapocrucet.com/), who said that she was told that she shouldn’t write from anger. But as she wrote her book, she saw rage as her source, and while writing her book, recognized that underneath her rage was grief.

In a panel called “How Do You Know You’re Ready?”, novelists shared stories about manuscripts they either sent to agents too soon or had locked in drawers, never to see the light of day. I realized that the question of when a book is complete is a universal question. The panelists seemed to agree that knowing when you’re done writing a book is a “visceral thing”. I was touched that the panelists also welcomed attendees to approach them with questions at the end of the session. I asked novelist Dawn Tripp (http://www.dawntripp.com/) for suggestions about making a “pitch” to an agent. She offered me a few tips, including “make it short and to the point”. And another panelist, Kim Wright, author of Love in Mid-Air (http://loveinmidair.com/), added that it’s important to maintain the voice of the book when you’re trying to get others interested.

In a session called “Memoir Beyond the Self”, panelists talked about the importance of writing from one’s personal experience and broadening it to reflect on cultural implications. Travel writer and journalist, Colleen Kinder (http://www.colleenkinder.com/Colleenkinder/home.html) said, “personal essays have to be brave”, and she talked about the importance of “braiding” and “weaving” different strands of a story together. In describing this braiding and weaving process, Leslie Jamison, author of Empathy Exams (http://www.graywolfpress.org/Latest_News/Latest_News/Leslie_Jamison_wins_Graywolf_Press_Nonfiction_Prize//) said that “something in one sphere poses a question that another sphere can answer”. That intrigued me.

In a session called, “It’s Complicated: Memoir-Writing in the Political Sphere”, Melissa Febos talked about her book, Whip Smart, in which she wrote about her three years as a dominatrix while attending a liberal arts college in New York City (http://melissafebos.com/). Kassi Underwood talked about her book, A Lost Child, but Not Mine (http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/fashion/a-lost-child-but-not-mine-modern-love.html?pagewanted=all), which chronicles her experience of having an abortion and then encountering her ex-boyfriend who was now a father. And Nick Flynn described the writing of his book, Another Night in Suck City about seeing his estranged father in the homeless shelter where he worked. The book was later turned into a film called, “Being Flynn” with Robert DeNiro and Julianne Moore. Talk about star struck!

In a session called “Poetics of Fiction in/at Buffalo”, three writers read from their work about my poverty-stricken, yet vibrant hometown of Buffalo, New York. Ted Pelton (http://www.starcherone.com/ted/) began with this poem: “Buffalo Buffalo, Buffalo Buffalo Buffalo…”, saying that no other city can be a noun, verb and adjective. And Buffalo writer of Buffalo Noir, Dmitri Anastasopoulos (http://www.akashicbooks.com/catalog-tag/dimitri-anastasopoulos/), brought the experience full circle for me, when he said, “Buffalo is all about loss”.

The conference had a commercial element as well: In a so-called “Book Fair”, the small presses are there to entice writers, as are the creative writing programs and artists’ retreats. But one of my favorite booths in the exhibition hall was run by 826 National, a nonprofit organization that runs eight writing and tutoring centers around the country, aimed at helping at-risk youth find a voice to tell their stories (http://www.826national.org/). And who knows? Perhaps these young people will be the authors of tomorrow, and future attendees of this chaotic but enriching experience that is AWP…

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?

I want to understand how these friends feel about their paid job as they consider “winding down”: What do they consider will supplant the intense time and commitment they have made to this work? Do they have fears about retirement? Do they have passions they plan to pursue, and plans in place? Do they view retirement as an abyss or a welcome opportunity, neither or both? What will the transition period away from paid work be like? Do they just stop working for pay one day, or do they gradually decrease their hours, and increase the time they spend doing unpaid work or having fun! (imagine that!) How happy are they after retirement, which may include how active they are and how social they are? And lest we forget, how does their health – or the health of their partner – factor into the equation?