by Mindy Fried | Mar 25, 2015 | applied sociology, gender, program evaluation, race, selecting evaluation researcher, social class, social justice, social science research, working with evaluation researcher

![]()

After working in the policy world in Massachusetts for many years, going back to graduate school in Sociology felt like going to a candy store in the country* every day, where I could read interesting books, have stimulating conversations, learn how to do research, and then write about it. I admired my professors, and I was kind of amazed that their job was to take me seriously and support my development as a scholar. Later, while I was working on my dissertation, I got a job teaching part-time in a local university while a full-time professor went out on leave. It was challenging; it was fun; and it was an incredible opportunity to experiment with pedagogy. I learned that I loved teaching, and over the next two years, got hired to teach a wide range of sociology classes – about families, sex and gender, feminism, work, and women and leadership – at several other Boston universities.

![]()

But the more I learned about the full-time tenure-track teaching world, the more I realized it was just not my thing. First off, I couldn’t imagine “starting over” again at the bottom of the career ladder, with what could be six grueling years of slogging towards tenure. Nor could I imagine the idea of a job for life – the promise of tenure – working with the same folks for the next few decades (apologies to my mythical could-have-been colleagues!). Call me fickle, but I enjoyed changing jobs every few years, having new and varied challenges, and working with a diverse array of people.

Learning on the job

By luck, while I was taking research methods classes, I was offered a small consulting job to evaluate the impact of a well-established training program on its activist participants. Here was an opportunity to put my newfound knowledge to use. Except that no one was teaching how to evaluate social programs in sociology graduate programs! I did have some experience with “program evaluation”. When I was directing a statewide child care project that was federally funded, some guy was hired by the state to evaluate my program. He met with me once at the beginning of the project, and at the end, he wrote a glowing report.

![]()

Every so often, I wondered if he’d be back. In the end, he really had no basis upon which to evaluate the strengths and challenges the project was facing – and believe me, there were plenty. But I wasn’t going to complain if he was phoning it in!

Since I had no idea how to evaluate a program, I hired someone who did, and for the next few years, she trained me and my sociologist friend, Claire, in how to use research skills to evaluate social programs. I never intended to continue doing this “applied” work for the next 20 years, but that is essentially what has happened. When I first started, I wasn’t very good at it, and I thought it was boring. But a couple decades later, I have learned a whole lot about how to do it well, and (luckily) find this work fascinating.

Making a choice to be an applied sociologist

The choice to be an “applied sociologist” is not a rejection or devaluation of academic sociology. It is a choice that is, in part, a function of economic imperatives – a tight job market, especially if you don’t want to move – but also a choice to make a different kind of difference. To impact the social world through organizations that are impacting people: through service, through organizing, and through education and advocacy, in the areas of public health, education, urban planning, climate change, arts and arts education and many more.

I have learned that it makes me happy to use the research and writing skills I learned in graduate school as a tool to help promote social change, through the vehicle of strengthening nonprofit organizations and improving philanthropic decision-making. Once considered the stepchild of the field, applied sociology is now gaining prominence, but largely because the economy has not produced the plethora of academic sociology jobs once predicted.

“Close to a perfect match”

In a 2013 article in Inside Higher Ed, Roberta Spalter-Roth, from the American Sociological Association, commented that “In sociology, there is close to a perfect match between available jobs and new Ph.D.s” (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/08/06/sociology-job-market-continues-recover-steadily). But this is only if you factor in the many government, nonprofit and research analyst jobs out there that require the skills and sociological perspectives learned in graduate school. Spalter-Roth notes that these jobs often pay more than university teaching positions, but graduates rarely know about them and professors may even discourage their students from entering these professions.

This year, my applied sociology friends and I agree that the “applied route” seems to be gaining some traction, with increased interest from universities and professional associations. A number of us have been on a (minor) speaking circuit, talking to graduate students at the request of sociology departments about choosing applied sociology as a career. And this year, the Sociology Department of a major research university, Boston College, hired me to teach a course on Evaluation Research. (Kudos to BC Sociology for recognizing the importance of this avenue for sociologists-in-training!)

Panel at Sociologists for Women in Society: Choosing Applied Sociology (sponsored by the Career Development Committee)

Given this increased interest, and what I believe is a need for sociologists to promote the health and well-being of organizations and communities using research and sociological principles, I organized a panel on this topic at an annual meeting of my favorite national feminist sociology organization, Sociologists for Women in Society.

The panel included three distinguished applied sociologists from the DC area, where the meeting was held, who presented about why they chose this route of practice, what they do and for what populations, and how they incorporate sociological principles into their work, framed by a race, class, gender lens.

The speakers, all based in DC, included Tekisha Everette, a lobbyist for the American Diabetes Association; Andrea Robles, a research analyst at the Corporation for National and Community Service; and Chantal Hailey, who ran evaluation projects at the national Urban Institute and elsewhere, and is currently a sociology doctoral student at NYU. One other panelist, Rita Stephens, was not able to make it because of a blasted snowstorm, but she would have rounded out the panel very nicely as she works at the State Department. The three women spoke to a standing and sitting room only crowd at the meeting, followed by numerous informal conversations, attesting to the fact that there is a hunger for this kind of work.

In my next couple of blog posts, I will allow these amazing women’s words speak for themselves. I hope that their words stimulate a dialogue about the value of and choice to pursue sociology outside of the academy. Based on the remarkable response at this meeting and in classrooms where I talk about applied sociology, my sense is that sociologists want to know about alternatives to working within academia. The words of these speakers inspired me and I hope they inspire you.

“I was interested in doing applied work that could lead to positive social

change. Somehow, it seemed like I wanted to be part of making the world

a better place.”

Sociologist, Andrea Robles

Corporation for National and Community Service

Check out this excellent blog post by Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, Research and Social Media Consultant with Social Science Insights in Australia, called What is Applied Sociology?, published in Sociology at Work: Working for Social Change: http://sociologyatwork.org/about/what-is-applied-sociology/

*Brandeis University, which is actually in the suburb of Waltham, Massachusetts, but looked like the country to this city girl!

by Mindy Fried | Feb 15, 2012 | blacklisted, education, House Un-American Activities Committee, HUAC, organizing, prejudice, protest, resiliency, social justice

I was on the treadmill at the gym the other day, frantically trying to undo a day of sitting and staring at my computer, when a casual “gym friend” joined me on an adjacent treadmill. She noticed that I hadn’t been there lately, and wanted to know why. I don’t know her well and could have manufactured some story, but she had always been so warm and friendly, so I decided to tell her the truth, that my 97-year-old dad had just passed away. Her response was immediate and kind, as she empathized with how hard it is to lose a parent. Then she looked up to the ceiling of the gym, and as I followed her gaze, wondering what had stolen her attention, she said in a reassuring voice that he was in heaven now, and then looked back at me with a smile. Not knowing how to respond, I smiled wanly and increased the incline on the treadmill. I wish I believed that he was in heaven and as my partner says, I hope to be happily surprised…

She then asked about the funeral, and I explained that we had it right away because I’m Jewish and that’s what we do… Apparently, distracted by the realization that I was a Jew, she then said that she had many arguments with her Catholic friends who believed that “the Jews killed Christ.” (Wait a minute – where did that lovely empathy go?!) Just as I was thinking about an exit strategy, she came back to earth and said, “It’s crazy that people of all faiths don’t get along.” And as I was mentally excusing her for that detour, she added, “except for the Muslims”. Again, I was hooked, and as I looked at her, I know I must have appeared surprised because she looked back at me with a slightly uncomfortable smile. And then went on to say that she worried that Muslims – presumably all Muslims – were terrorists. Wasn’t it time for me to leave the cardio area and work on my abs or something? But no, I couldn’t leave now, as this was a “teachable moment.”

I said that the media would like us to believe that all Muslims are terrorists, but most Muslims are peaceful people. And she asked me, didn’t I think that the “Koran incites Muslims to commit terrorist acts?” I replied with certainty, with whatever knowledge I have accumulated since 9/11, that that was untrue.

This really bugged me, a kind-hearted, well-meaning person swallowing Fox News whole. And it really upset me that the media is so compelling that good people can believe such nonsense.

I learned the hard way from my father not to run away from difficult conversations and to stand up for my beliefs. In the 1950s, and again in the 1960s, he was called before the Senate House of Un-American Activities (HUAC) to answer the now-infamous question, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party (CP) of the United States?”. The first time he was subpoenaed before the committee, he challenged its legality. And the second time, he used the first amendment, declaring his right to freedom of speech. As a result of the first committee hearing, he was “blacklisted” from work in the U.S., and ultimately sold life insurance for 15 years through a Canadian firm. He also became a prolific playwright, writing about his experiences within the labor movement in attempt to give voice to working people.

It was not until I was well into my 30s that my father admitted to me that he had been a member of the CP, but had wanted to protect me in case the FBI approached me with that question. That might seem like crazy-thinking, but the FBI actually did follow my father – and consequently, our family – for half a decade, employing agents to observe meetings where my father spoke, reviewing documents he wrote, including plays and memoirs, and even observing the fall-out we experienced in our family, as a result of being persecuted by the government.

When I left for college, my father warned me that I might be approached by an FBI agent, asking about his political activities. At the time, that seemed ridiculous, the product of narcissistic, paranoid thinking. But in my junior year, a guy from the Dance Club – in which I was very active – began asking me questions about my dad. Through some research, I discovered that he had been working out in California, trying to sabotage the Cesar Chavez grape boycott. I realized that maybe my father’s paranoia wasn’t so crazy after all. Using the Freedom of Information Act, my father ultimately received roughly 5,000 pages of FBI notes, with many of the words redacted (meaning crossed-out!), supposedly to “protect” the identity of the agent who was following him. I spent hours pouring through these files a number of years ago, and was stunned to read that the FBI knew that my sister and I were being ostracized by our so-called friends because of my father’s political beliefs, and that my mother lost many dear friends and family members to the fears they had about being associated with “a Communist family”. You can read more about this in Colin Dabkowski’s article in the Buffalo News:http://www.buffalonews.com/spotlight/article727714.ece

After my mother died, my father told me another reason why he left the Communist Party. He didn’t want that admission to have negative repercussions on his CP colleagues and friends. He was a working class Jewish man who had strong convictions and was loyal to his friends, risking a lot to stay true to them. He wasn’t trying to overthrow the government, although he was challenging an economic system that, even more so today, creates haves and have-nots. He was simply a very effective labor organizer who mobilized workers around issues of wages and benefits and fair treatment on the job. In doing this work, he was simply executing his first amendment rights to speak out about his beliefs. I believe that the world was a better place because of people like him.

So what to say to my friend at the gym, who seems to have drunk the kool-aid of misinformation in the right-wing media? What to say to many of my fellow Americans who are now stumped about whether to support a wealthy businessman for President whose personal and political interests are intertwined or an evangelical politician who would happily turn our country into the United Christian States?

There are many ways to fight disinformation and work for a better, more equitable world, through organizing, writing, teaching, and just speaking to friends, colleagues and acquaintances. And we must not be afraid to do so.

by Mindy Fried | Apr 30, 2011 | immigrants, organizing, social justice

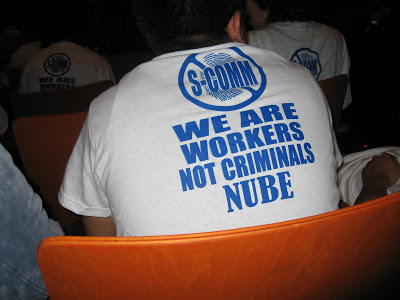

Last night I went to a rally and public hearing in Chelsea, Massachusetts about the “Secure Communities” program. For those of you who are unfamiliar with this program – as I was up until recently – it would increase federal authorities’ access to information about immigrants who are suspected of committing a crime.

Currently, police now have the technology to take the fingerprints of crime suspects and share them digitally with other state officials around the country, to see if they surface other crimes. Under “Secure Communities”, the U.S. Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) would have access to the technology of state officials, including suspects’ fingerprints and background information.

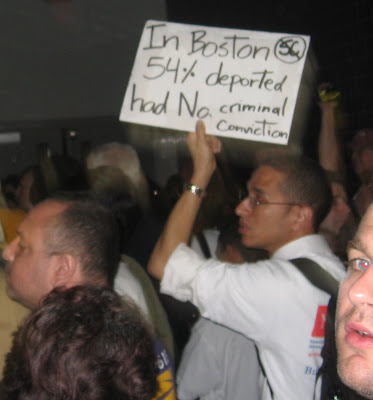

The program was supposedly started by ICE to identify serious criminals, but it turns out that the majority of people identified by Secure Communities have minor or no criminal convictions. In fact. in Boston, where the program was piloted, over 50% of the immigrants who were arrested and deported were in this category! Nonetheless, the federal government plans to implement the program – to be administered through state agencies – by 2013.

Given this federal mandate, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick has stated that he will comply with the program. Last year, a number of jurisdictions around the country – including San Francisco and Santa Clara – requested to opt-out of the program, but they were given mixed responses from federal officials about how the opt-out process works. First, the administration said that opting-out was allowable, and then they reversed their position, saying that the program was not voluntary. Finally, in an official response, ICE said that “Secure Communities is not voluntary and never has been. Unfortunately, this was not communicated as clearly as it should have been to state and local jurisdictions by ICE when the program began.” What?!

It turns out that Governor Patrick only scheduled these hearings following pressure by community-based organizations that focus on immigrant rights. In response to the “Secure Communities” program, a non-profit called Centro Presente launched a “Just Communities” campaign, in collaboration with the ACLU of Massachusetts and the American Friends Service Committee. Their campaign included high visibility events like rallies in front of the State House, and hand delivery of 1,000 protest postcards to the Governor.

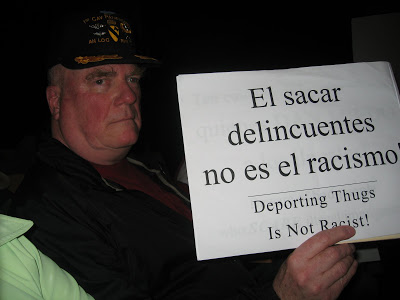

Last night, at the Chelsea hearing, opposition to the program came through loud and clear. Over 200 people jammed into the auditorium of the local high school, mostly to voice their opposition to the “Secure Communities” program. Before the event, there was concern that the Tea Party would show up and be disruptive, as they had been at another hearing in Waltham, Massachusetts. And sure enough, a small but vocal group was there. I happened to sit next to two Tea Partiers. Given the “otherness” with which these folks are painted – and the outrageous behavior of many of their leaders – I felt a certain trepidation and immense curiosity about who they were and what they were thinking throughout the evening.

The hearing began with a public official from the state’s Public Safety office, explaining how the system functioned to track criminals. His voice was monotonous, designed to make the most patient listener edgy. Backed by an uninspired Power Point presentation, he droned on and on, and the crowd got restless. His main points, which he made over and over again, were two-fold. First of all, he said that the “Secure Communities” program only involved procedural changes that would allow state officials to share information about suspects with federal immigration officials. Skirting any potential policy implications, the official described the program as if we, the audience, were simple people who just might not understand the complexities of government. His second message was that this program was going to be implemented, regardless of public concerns, and that the role of the state was to figure out how to best accomplish this goal.

So what was the point of these hearings? Why bother asking us what we think of the program? There was something odd about this introduction that said, ‘basically, this is going to happen anyway,’ when clearly, the door for dialogue and debate is still open…

I wondered if the purpose of this state official’s droning speech was to take up time, so we’d have less time for public testimony. But sure enough, he finally finished and the audience was invited to line up along the side rows of the auditorium to take turns commenting and asking questions.

My Tea Party friends sitting next to me were busy. The woman adjacent to me was videotaping the entire event, and her partner – who carried a series of signs in support of the program – was tallying how many people spoke out for the program and how many spoke out against. Given my curiosity about them, I tried to make small connections. I asked the woman if she could lend me her pen and we smiled at one another. And when people were looking for seats, we both raised our hands and pointed to the seats in our row. I donned my sociological eye and thought of this as a “research-able moment”.

One by one, Latino immigrants shared heart-felt stories of working hard to contribute to this society and their sense of betrayal with this program. The audience cheered in support. Many shared stories of being racially profiled, or stories of friends who were deported unfairly to countries where they were not safe. Again, the audience cheered. An elderly Chinese immigrant spoke with the help of a translator, saying that we are all immigrants to this country, as the crowd stood up and burst into applause. And when he walked away from the microphone, audience members reached out to shake his hand in solidarity. Many white audience members spoke about being second or third generation immigrants, bridging the gaps between first generation immigrants and nearly everyone else in this nation. Again, the audience cheered. A lawyer from the Center for Constitutional Rights told us that there were a couple of lawsuits challenging the legality of the program, and her comments reassured the audience that there was, in fact, recourse. And several others spoke about the danger of “Secure Communities” for women victims of domestic violence as it might deter them from reporting abuse for fear of being deported if they are undocumented.

Interspersed between the 80 or more speakers who opposed “Secure Communities” were roughly 10 Tea Party speakers who supported the program. With some, it was evident that they were Tea Partiers from the moment they opened their mouths, because they started with inflammatory comments like “immigrants are criminals.” But the most controversial Tea Partier who spoke was a Latino man who loudly declared his support for the program because he said it would get rid of immigrants who were criminals. When the crowd began to “boo” him, he shouted defiantly, “Soy Dominicano y soy un Team Partier!” (I am Dominican and a Tea Partier.). And as he loped back to his seat, he nodded to his fellow (white) Tea Partiers, punching his fist in the air.

At the end of the hearing, as we were all putting on our coats and preparing to leave, I turned to my Tea Party friend and asked her what she planned to do with the video she had been shooting. She kindly responded that she would put it up on YouTube for those who weren’t able to be there. I asked if she was a member of the Tea Party, to which she answered, yes, and then replied by asking if I was in the Tea Party too! That surprised me, and made me realize that she wasn’t paying any attention to my hoots of support for those who opposed the program! I wondered what she was thinking about what she had just heard. After all, we had both spent the past hour listening to the same speakers and many of their compelling stories. So I asked her if any of these stories had moved her to think differently. She looked at me with a pained expression, and said, yes, particularly the women who were victims of domestic violence. ‘But what can we do?,’ she implored. ‘We need to deal with the criminals! We need to change the police chiefs!’, she exclaimed. And with that, we walked in separate directions.

What will come of these hearings? Will the Governor take this outcry seriously, and consider opting out of the program? I certainly hope so, but I now realize that the pressure for him to do so comes from a number of directions, including the legal strategies being pursued by advocacy organizations, legal strategies in motion because of a powerful Congresswoman, AND the people in that high school auditorium. I left the meeting feeling satisfied and proud of the amazing people in that room who had the courage to speak out and express their outrage at a policy that doesn’t produce the outcomes it’s intended to produce, and in fact, creates more insecurity in our communities. It was this sense of community – created in that room – that gives me a sense of security.

by Mindy Fried | Mar 14, 2011 | family, loss, social justice, value of caregiving work

Joan and Warren lived next door. They were in the first-floor apartment of a modest, fading yellow, two-family house. Father and daughter, they had been living in that apartment for some 15 years. Before that, they lived in an apartment down the street, but the landlord raised the rent far beyond their means, and gave them no option but to move out. At the time, the neighbors were outraged. In their neighborhood, they said, people stayed forever, so the idea that a landlord could throw out one of their own was antithetical to “how things were done around here.” Shunning the landlord, the neighbors banded together and found them another apartment right down the street. When Joan and Warren moved into the faded yellow two-family, they pledged never to move again. People lived their whole lives in this neighborhood. Why shouldn’t they?

Despite an age gap of 30 years, many people mistook Joan and Warren for husband and wife. Maybe it was how they related to one another; maybe it was how they finished each other’s sentences, or made similar sarcastic jokes with a twinkle in their eyes. Joan and Warren even looked alike. Not just a little alike, but a lot alike, with but a few distinctions. Warren was large and tall to Joan’s short and stout. Joan hid her plump body in old wool, Catholic-plaid smocks, and comfortable old sweaters that united any division between breasts and belly. Warren wore flannel shirts and baggy pants, held up by a worn leather belt that had an extra six inches hanging off the buckle. Both of them had chins that receded into their necks, doubling and tripling in folds of skin. But Joan’s chin was framed by curly, blond waves and Warren always covered his head with a railroad hat he constantly readjusted.

On the weekdays, Joan left early for her teaching job at a local parochial school, but after work and on the weekends, she devoted herself to her father. Despite her easy-going personality, Joan didn’t seem to have many friends. In fact, Warren – her father – appeared to be her only friend. Since Warren’s knees “went” on him years ago, as he told me, he wasn’t able to walk very well, so he rarely left the house. Despite his maladies and the relative sameness of his days, Warren managed to maintain a chipper demeanor, sitting on the front porch in good weather and watching the world go by. He was limited by his health, and rarely had visitors, but he always seemed upbeat.

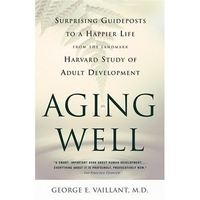

According to Harvard University-based psychiatrist George Vaillant, who studied the lives of 824 men and women over a 30-year period, “objective good physical health (is) less important to successful aging than subjective good health.” In other words, older people continue to function pretty well, as long as they don’t feel sick, and while we didn’t know much about Warren’s health, he certainly did not project the image of a sick man.

My daughter once interviewed Warren for an elementary school project, one of those-talk-to-someone-who-lived-through-the-war assignments. When we rang their doorbell, we could hear Warren shuffling slowly to open the door, accompanied by the thump-thump of his cane. Opening the door with a welcoming smile, we could see that he was tickled we were there. And as we entered their cluttered, old-fashioned apartment, we were struck by the sweet smell of Joan’s homemade brownies she had baked for this special occasion. As my daughter nervously prepared to ask her questions, Warren said self-deprecatingly, “What do I have to say?”, with the emphasis on the word, “I”. And then he launched into stories of his past.

After the interview, I didn’t see Joan and Warren for a few weeks. Joan’s schedule was hectic, she told me one day, when we ran into her. The end-of-the-year school party was coming up, and her kids were “goin’ nuts,” she said. And then she chuckled, letting us know that she actually liked the chaos of her kids going nuts. She also told me, almost in passing, that her landlady, who had been in a nursing homes for many years, had just died. This meant that the owner’s family would have to decide what to do with their house. It had never occurred to me that Joan and Warren might face another change…

But pretty soon the activity around the house picked up, as estranged family members began to lay claim on items they had inherited. Hungrily, they dragged out furniture, appliances, aged stereo equipment and pottery, hauling them into station wagons and SUVs. They also discovered that what used to be a working-class neighborhood many years ago had become a gentrified, sought-after neighborhood; and what had been an inexpensive house many years ago had soared in value. Rumors began to fly about what the family would do with the house. Would they sell it? Would one or some of them move in? And what would happen with Joan and Warren?

Finally, the house went on the market, and for two weeks, hoards of buyers came and went, gliding with ease through the upper two floors of this simple home, its rooms clean and ready for the next owner. They seemed to save their perusal of the first floor until last, more daintily tiptoeing through Joan and Warren’s apartment, which was cluttered with memorabilia, dusty with age and daily living.

When they reached the living room, there sat Warren, firmly planted in front of his television set, refusing to move to make it easier for real estate brokers to “show” the house. He was a part of the house, almost seemed like he came with it, one might say. So why should he move, just so some rich people could sashay through the house, looking at its “potential”. As the days progressed and no one had ostensibly made an offer on the house, there was rumor that maybe the market had slowed down. But after a couple of weeks, the house sold at a good profit.

Joan and Warren hoped that the new owners wouldn’t raise the rent, but they were getting nervous. When I saw Joan the next day, her eyes were red and her face bloated. “What will happen now?”, I asked. She shrugged, looking embarrassed. “I’m not sure, but the new people seem pretty nice,” she replied. Maybe they would stay, I thought, feeling more hopeful for them. I wished her “the best of luck,” then felt the emptiness of those words. Shortly after we spoke, Joan got into her car and drove off to work.

When she drove back into her driveway later that day, her car was filled with empty boxes, in anticipation of the inevitable move. She slowed her car down for a group of kids playing soccer in the street, and waved first at them and then at the parents who were monitoring them. Slipping into her house, she self-consciously avoided conversation, but the parents on the street were painfully aware of her presence and concerned about both her and her father. Another parent and I started talking about helping her find a new home, but our conversation was interrupted by a piercing scream, coming from inside their home.

Somehow at first, the kids didn’t hear it. In the midst of their game, maybe it seemed like just another loud sound. I ran to Joan and Warren’s front door, which was ajar, and let myself into the apartment. And there, on the floor, was Warren, lying motionless, with Joan lying on top of him, sobbing…

The next few hours, we all learned that Warren had died of a heart attack. The younger kids were initially oblivious, but the older ones, particularly my daughter and her best friend, began to cry. The cries became wails that were deep and loud and persisted for about an hour, capturing a raw grief that many of the adults shared but couldn’t express so freely. As the ambulance came and took Warren away, the younger ones were shuffled back to their homes, perhaps to protect them from that visual impression, and certainly to respect Joan in that painful moment.

Would it be too simple to say that gentrification killed Warren? It would be hard to make the causal connection, but perhaps there is a correlation, as Warren was forced to experience the stress of losing his home, again. Ironically, Warren was right when he claimed that this was going to be his last home. Ultimately, the power of the market won, as the highest bidder got the house, and with it, the legal right to determine whether or not to raise the rent, or for that matter, to take over the whole house. That evening, my daughter remembered that she had the tape from her interview with Warren, and asked if she could give it to Joan. “Sure,” I said, “but let’s wait a little while.”

by Mindy Fried | Mar 3, 2011 | family, loss, memories, organizing, social justice

My father just died. My 98-year-old, fearless, outspoken father – who was devoted to fighting for the rights of workers – just died. He hung on for over a year, despite major organ failure, with incredible determination and will. Just the way he lived. Even towards the end, despite the challenges and limitations to his body and mind, he was energized by the protests in Wisconsin, as state workers – police, firefighters, nurses and more – fight to maintain their right to bargain collectively.

In the 40s and 50s, my father was unafraid to speak up for working-class people who toiled in factories. This was his organizing base, and as a child of the 50s, it seemed very foreign to me in my middle-class world. I was schooled by the antiwar movement, the women’s movement and gay/lesbian rights movement, all a far cry from the world of factory workers who made auto or typewriter parts.

In the 40s and 50s, my father was unafraid to speak up for working-class people who toiled in factories. This was his organizing base, and as a child of the 50s, it seemed very foreign to me in my middle-class world. I was schooled by the antiwar movement, the women’s movement and gay/lesbian rights movement, all a far cry from the world of factory workers who made auto or typewriter parts.

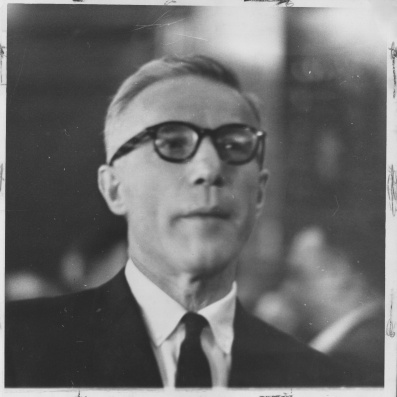

|

| Manny speaking before House Un-American Activities Committee 1964 |

|

But I absorbed my father’s social justice values, even though I felt very separate from the people he was organizing. It was hard for me to imagine the unfortunate plight of the factory worker, but over the years, I began to understand the need to fight against inequities around workers’ wages and working conditions. And once I was in the work world, I learned first-hand what it meant to be caught in a stratified social structure that appropriated varying amounts of power to its employees. In fact, a string of lousy work experiences was one thing that inspired me to study workplaces once I became a sociologist. I discovered first-hand that worker control is the key to job satisfaction, and many people don’t have enough of it…

I was once on a plane with a factory owner, and over the course of our flight, discovered that this guy’s plant – Remington Rand – was one that my father had organized. Listening to him talk about how he decided to move the company abroad, and how he couldn’t understand why his workers weren’t willing to move with him, I realized how out of touch he was with the reality of his workers. I knew more about him than he could have possibly known. My father had led the workers employed by that man in a successful strike against the company, and the workers forced the company to back down on cutting wages and benefits. I decided not to share this information, but found great satisfaction in knowing…

At my father’s funeral this past Sunday, I told the congregation that if he were still alive and well, he’d be in Wisconsin. This was his fight, something to which he dedicated his life, through his organizing work, and then later through plays he wrote about worker-management struggles. The nature of the “working class” is different today, as factory work has moved to locations with cheaper labor. Wisconsin workers represent the “new” working-class, whose self-identification is folded into our broadly defined middle-class. They are service and professional workers who provide the critical supports to our society – regulating safety, putting out fires, teaching our children, maintaining our sewage systems, and caring for the sick.

There are far too few heroes these days, people who are willing to stand up against adversity to speak their piece and demand justice. My father chose to do just this. It wasn’t always easy to have a father who prioritized the outside world over his family. In fact, I learned early on that if I wanted to be close to him, I had to speak his language. I tried very hard – sometimes too hard – back then. And the older and more knowledgeable I became, the more I realized where we differed. But at the very base, I valued his commitment to a set of ideals, even when they created adversity for him and for us. He always hoped that we would see he made the right choices. And in the end, as a daughter to a loving father who became more emotionally generous with age, I feel that he did.

|

| Manny receives Joe Hill Award from AFL-CIO Labor Heritage Foundation |